To understand what configurational isomers are, let’s define/describe the terms “configuration” and “conformation”. Configuration is the orientation/direction of the atoms that we cannot change, whereas conformation is the orientation of the atoms which we can change via rotation about a single bond(s).

The best way to bring up some examples of conformations is what we saw in Newman projections of butane. There were syn, anti, and gauche conformations, and they were all interchangeable because of the free rotation about single bonds at ambient temperatures:

Notice that the gauche conformations are mirror images of each other, and they are also nonsuperimposable. So, technically, we could say that they are enantiomers, but we’ll see why we normally do not.

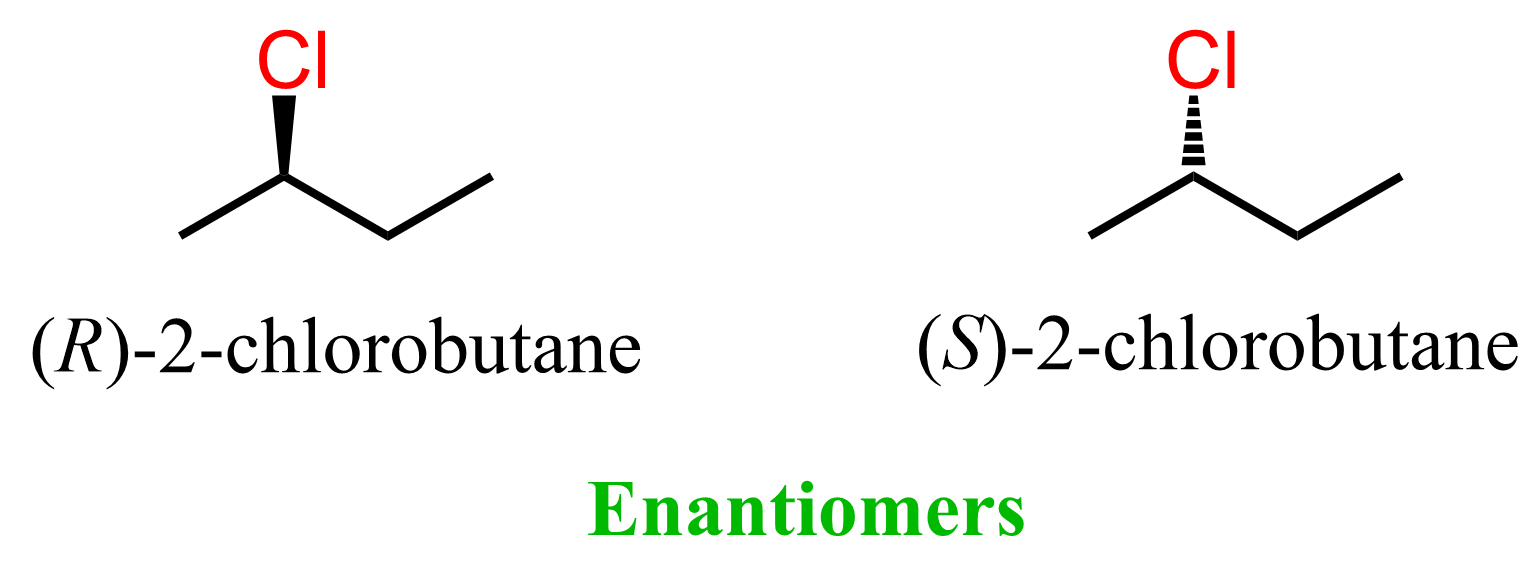

Let’s now replace one of the hydrogens with chlorine and discuss the structure of 2-chlorobutane. We know that it exists in two stereoisomers – the R and S enantiomers.

Unlike the two gauche conformations of butane, the enantiomers of 2-chlorobutane cannot be interconverted by rotating any of the single bonds in the molecule. Therefore, the arrangement of the atoms at the chiral center is the configuration of this atom. We cannot change the configuration unless we break and reconnect the atoms differently, but this is already a chemical reaction we are talking about. This is why it is called “R and S configuration”, not “R and S conformation”.

Another example of configurational isomerism is the cis and trans isomers. Like in the case of R and S configuration, we cannot interconvert cis and trans isomers by rotation about any single bonds, and remember, there is no rotation about a double bond. As an example, compare the interchangeable conformations of 1,2-dichloroethane and cis and trans configurations of 1,2-dichloroethene:

Recall that cis and trans configuration pertains also to ring structures because of the restricted rotations about single bonds. For example, 1,2-dimethylcyclohexane can have a cis or trans configuration depending on the relative orientation of the methyl groups:

To summarize, we can conclude that most of what we have/are discussed in stereochemistry about enantiomers and diastereomers pertains to configurational isomers. Enantiomers and diastereomers are configurational isomers.

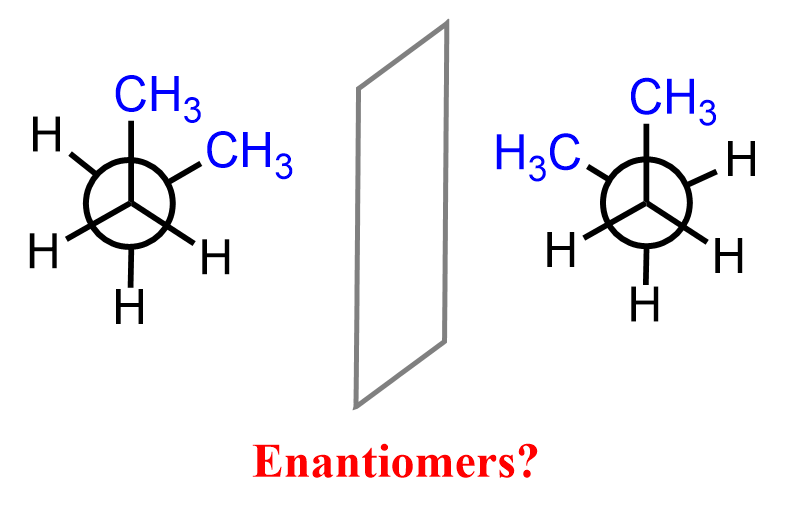

This is not to say that conformational isomers cannot be enantiomers or diastereomers. Any “innocent” molecule such as butane can also have an enantiomer, which we can see from the Newman projection of the two gauche conformations:

So, the question you may be wondering about why we do not normally classify these as enantiomers is answered by the fact that the molecules do not freeze in one conformation. If we could freeze two molecules of butane in the given gauche conformations, they would’ve been classified as enantiomers. More specifically, we shall call those “frozen” conformations conformational enantiomers as the two molecules are conformational isomers. This does not happen at ambient temperatures, and in fact, we know that rotations about single bonds occur very fast thus the conformations are practically indistinguishable, and the chirality of conformational enantiomers has no practical significance.

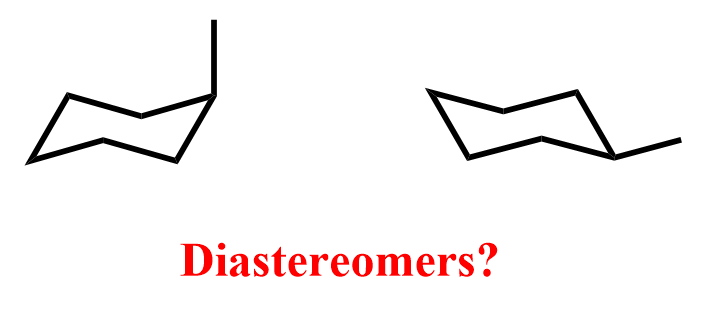

Another such example would be two chair conformations of methylcyclohexane:

We always say that these two structures represent the same molecule, and this is again because they interconvert very rapidly (ring flip). If they didn’t, we would classify them as diastereomers because they are stereoisomers that are not mirror images of each other.

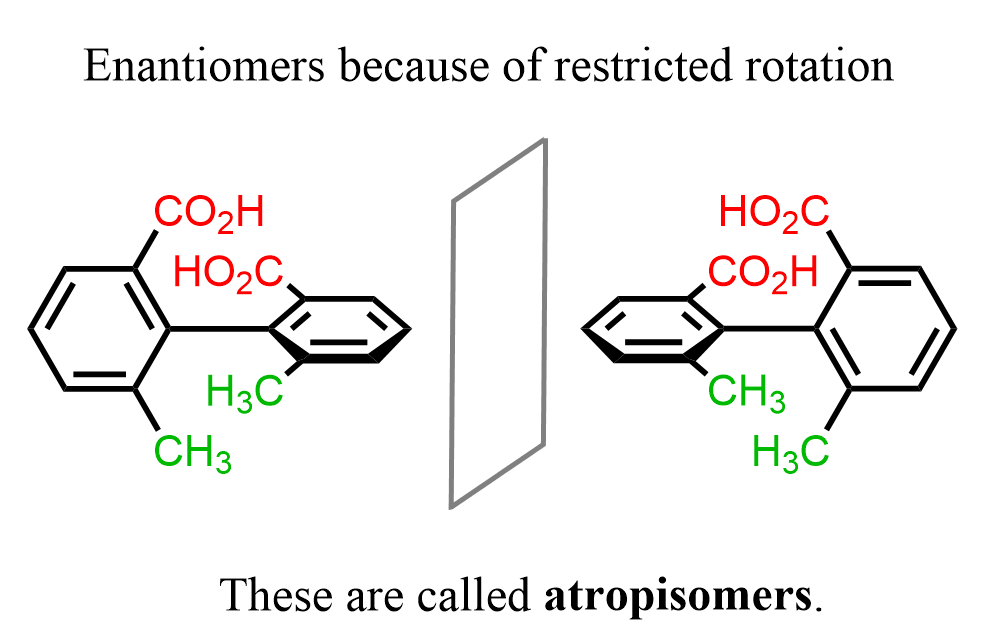

Atropisomers – Restricted Rotation About Single Bonds

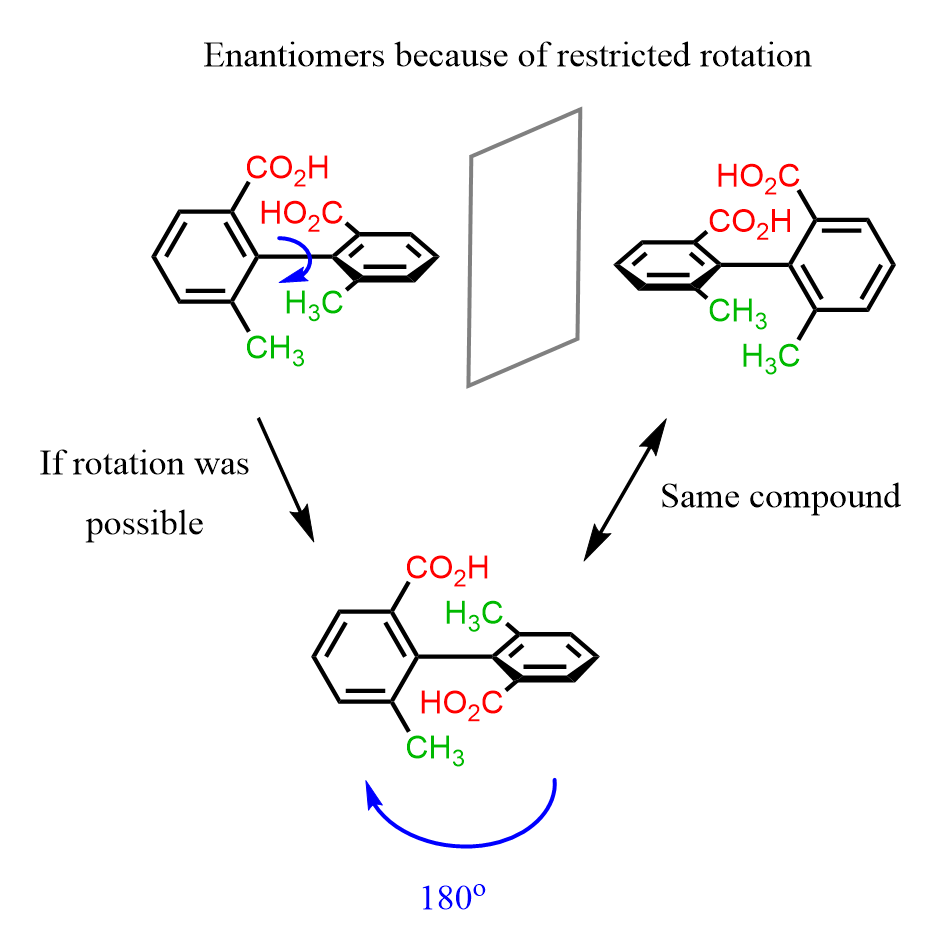

Because of steric hindrance, the rotation about single bonds is restricted in some molecules and they are chiral despite lacking a chiral center. For example, ortho-substituted biphenyls may be chiral because the groups are on each other way and there is no free rotation about the single bond connecting the two phenyl groups:

The two conformation of biphenyl shown above are enantiomers called atropisomers. These are stereoisomers that that lack a chiral center but are nonsuperimposable mirror images because of hindered rotation.

Notice that if we could rotate about the single bond, the two structures would represent the same compound which confirms that they are not constitutional isomers as it may seem like:

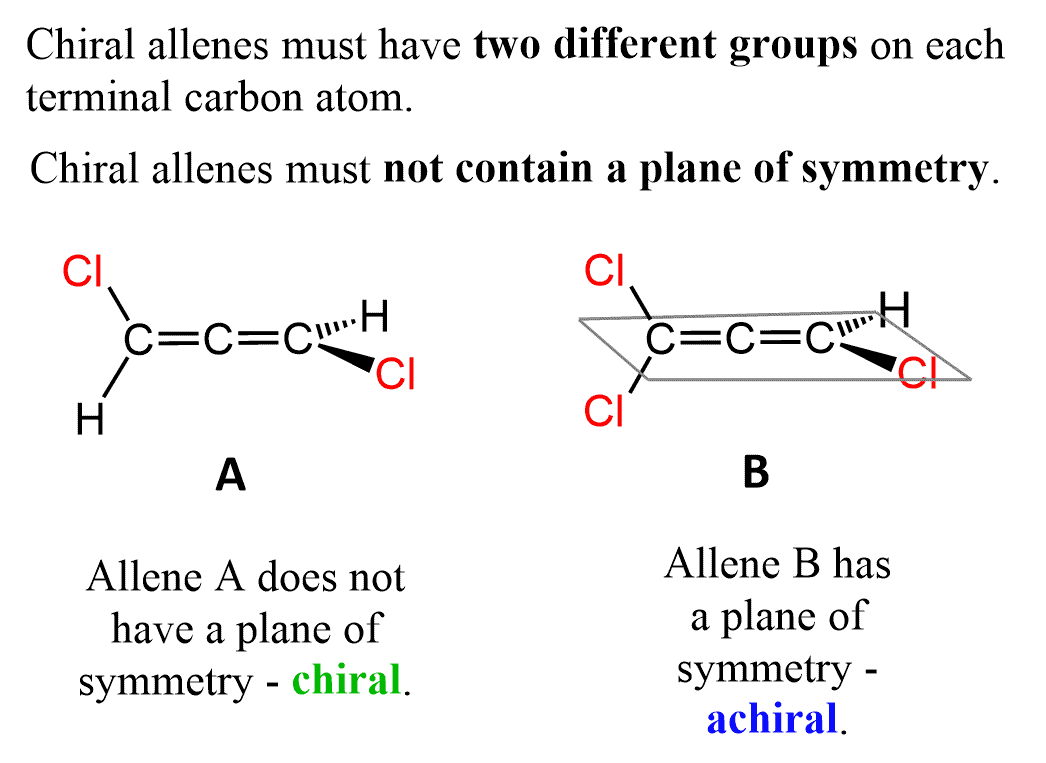

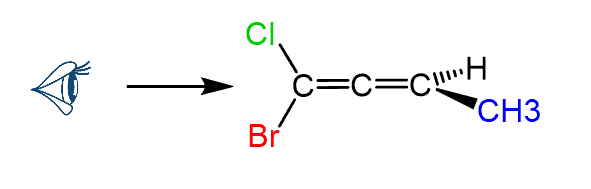

Although not identical, a similar type of isomerism is also observed in allenes, and we have a separate post determining the relationship and absolute configuration of allenes here:

In general, the chirality that is due to the presence of a chiral carbon atom is called central chirality. This is what we normally refer to when talking about chirality – a carbon connected to four different atoms. In the case of asymmetrically substituted biphenyls and allenes, there is no chirality center and the molecule is chiral due to axial chirality. In simple words, it is a chirality due to an asymmetric arrangement of atoms around an axis:

Let’s put together everything we discuss today in a chart summarizing the types of isomers and the relationships among them.

The enantiomers and diastereomers on the right side of the chart are not what we normally see in class because these are conformational isomers, and their chirality has no significance at ambient temperatures because of quick interconversion.

Check Also

- How to Determine the R and S Configuration

- The R and S Configuration Practice Problems

- What is Nonsuperimposable in Organic Chemistry

- Chirality and Enantiomers

- Diastereomers-Introduction and Practice Problems

- Cis and Trans Stereoisomerism in Alkenes

- E and Z Alkene Configuration with Practice Problems

- Enantiomers vs Diastereomers

- Enantiomers Diastereomers the Same or Constitutional Isomers with Practice Problems

- Optical Activity

- Specific Rotation

- Racemic Mixtures

- Enantiomeric Excess (ee): Percentage of Enantiomers from Specific Rotation with Practice Problems

- Symmetry and Chirality. Meso Compounds

- Fischer Projections with Practice Problems

- R and S Configuration in the Fischer Projection

- R and S configuration on Newman projections

- R and S Configuration of Allenes

- Converting Bond-Line, Newman Projection, and Fischer Projections

- Resolution of Enantiomers: Separate Enantiomers by Converting to Diastereomers

- Stereochemistry Practice Problems Quiz