In this article, we will summarize and compare the reactions of Grignard (RMgX), Gilman (R2CuLi), and organolithium (RLi) reagents. Let’s first see what unites and makes their properties similar or at least creates a pattern for us to predict the major products in their reactions with typical electrophiles such as carbonyl compounds.

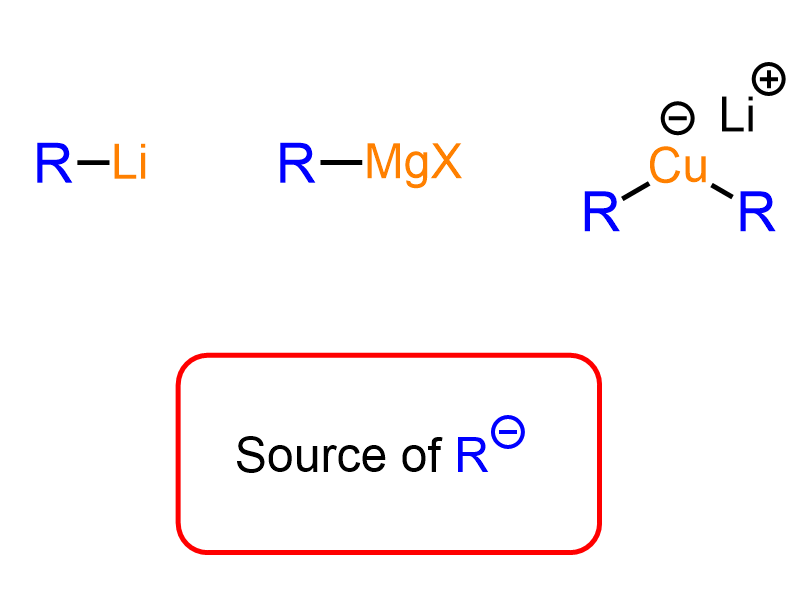

They are all called organometallics, meaning there is a carbon connected to a metal, and we know that metals essentially “lack” electronegativity, which makes these reagents a source of a negatively charged carbon atom. So, even though the C–Mg, C–Cu, and C–Li bonds are covalent, for the purpose of understanding their reactivity, we can look at them as suppliers of R⁻ species:

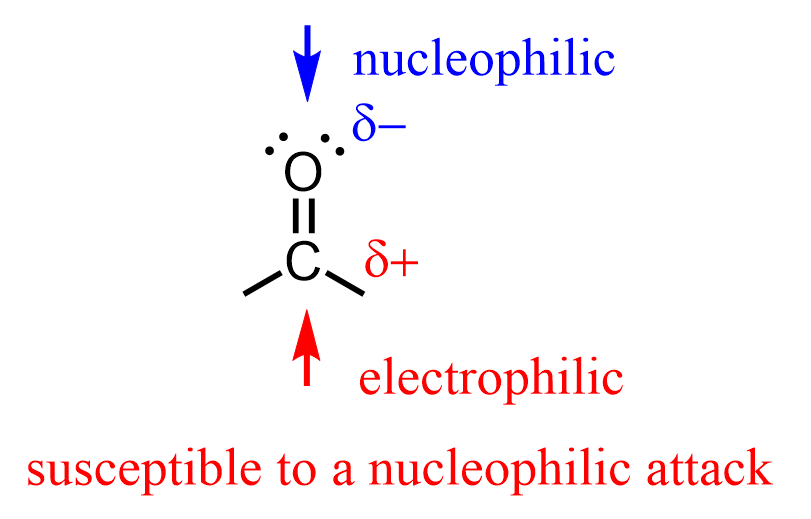

The R⁻ species are great bases and nucleophiles. Therefore, when reacted with compounds containing electrophilic centers such as the carbon atom in the C=O carbonyl bond, we observe nucleophilic addition to it, resulting in different final products.

For example, reacting aldehydes and ketones with Grignard and organolithium reagents, followed by an aqueous workup, gives secondary and tertiary alcohols, respectively. These are formed as a result of one nucleophilic addition to the carbonyl.

The situation is a little different when we use esters. The product is still a tertiary alcohol, like in the case of ketones; however, this time it is formed as a result of two nucleophilic additions to the carbonyl group. The first one forms a ketone, and the second one reduces it into a tertiary alcohol:

We have all of this covered in the linked posts, including the reactivity of aldehydes, ketones, and esters, the corresponding mechanisms, and more, so check them out for more details, as this post is a summary intended to give you the big picture and help you connect the key concepts quickly.

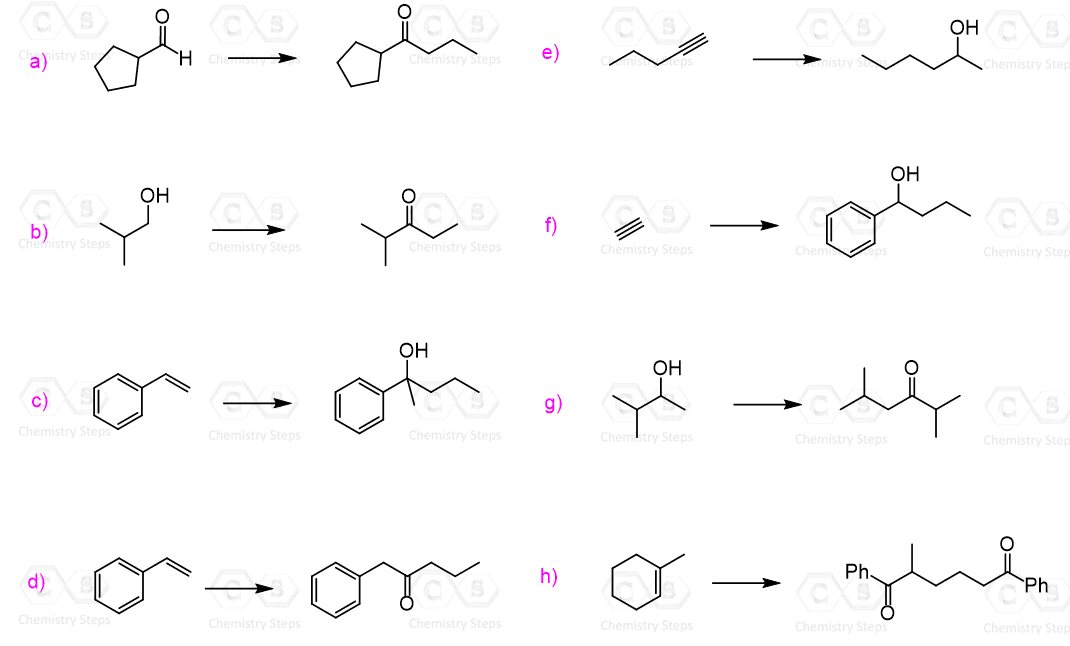

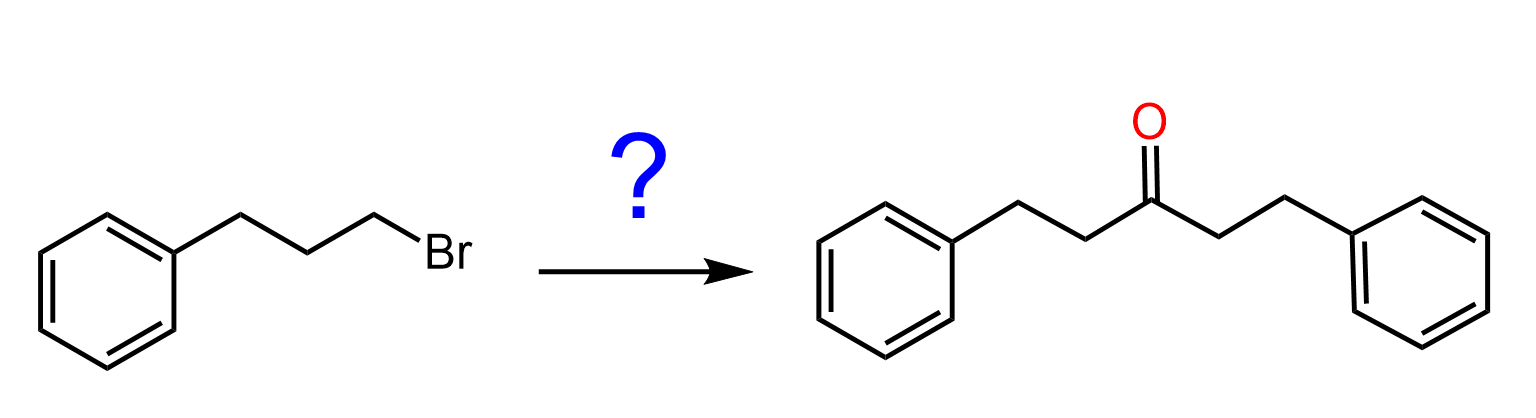

Now, what happens when we use an organocuprate instead of a Grignard or organolithium in these reactions? It turns out, most of the time, these are not reactive towards aldehydes, ketones, and esters. In fact, organocuprates are mainly reactive towards acid chlorides and α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds.

Why is that the case? In simple terms, this has to do with how polarized the C–metal bond is. In other words, how much electron density, and thus negative charge, the carbon bears. The least reactive in this sense are the organocuprates, and they only attack acid chloride carbonyl groups because these are the most reactive carboxylic acid derivatives. One nucleophilic addition forms a ketone, and that’s where the reaction stops:

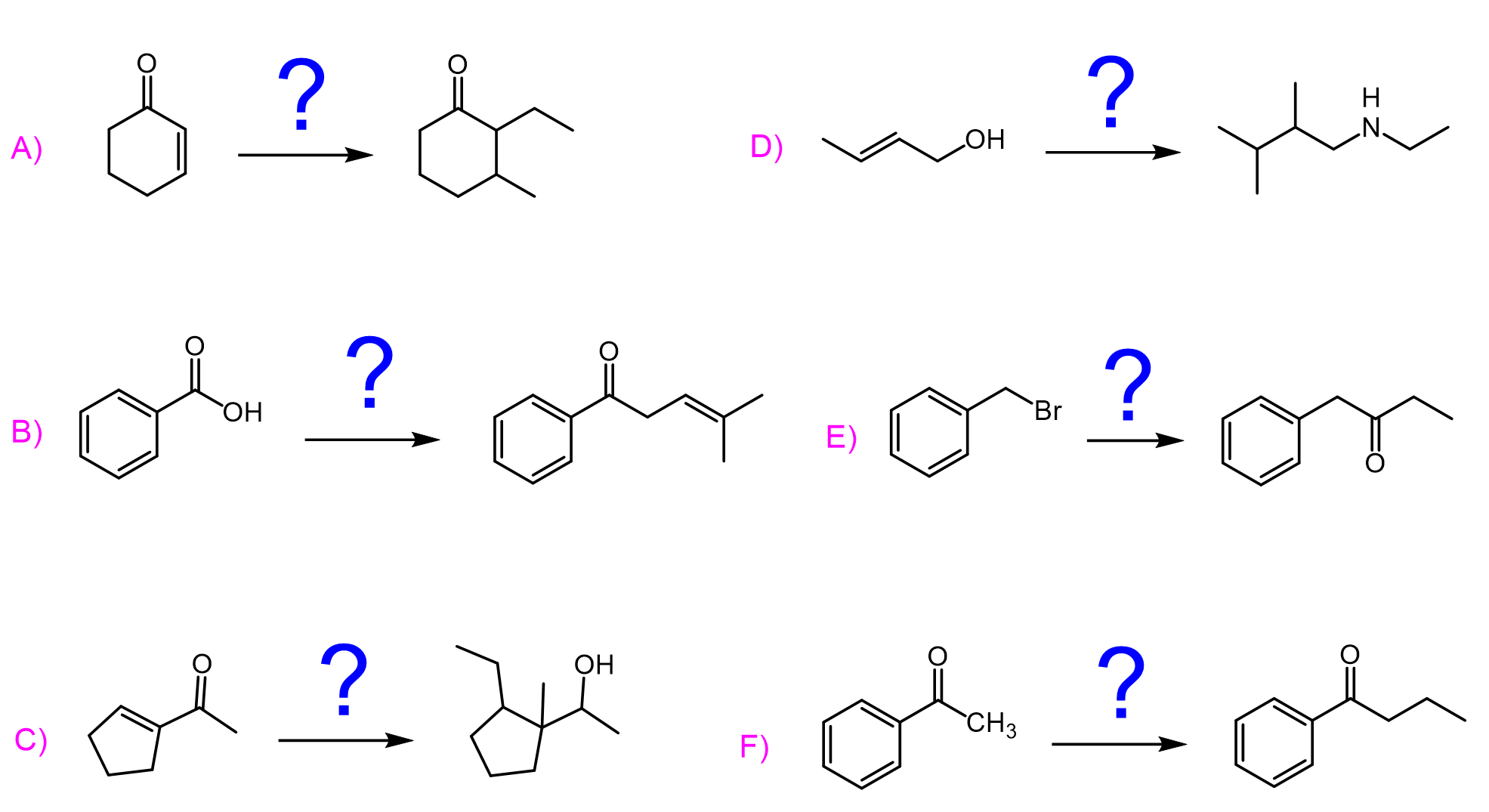

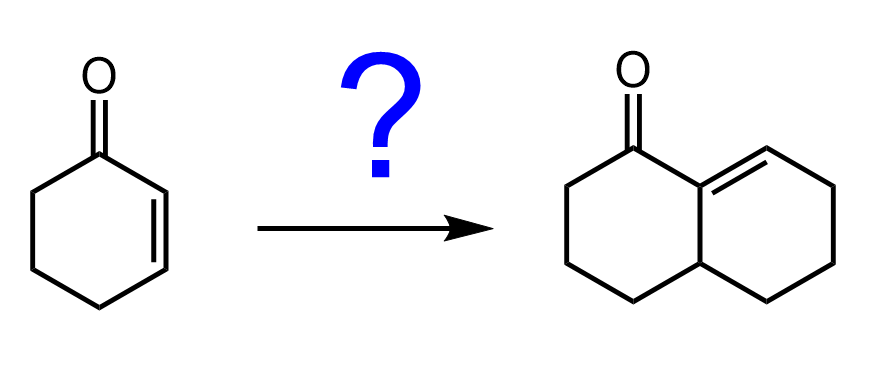

Let’s now compare the reactions of these organometallics with α,β-unsaturated compounds.

These substrates contain two electrophilic sites we can see from the corresponding resonance structures:

- the carbonyl carbon (position 1), and

- the β-carbon (terminal – position 4), activated by conjugation with the carbonyl.

Which site is attacked depends on whether your nucleophile is hard or soft:

- Grignard and organolithium reagents are hard nucleophiles — they prefer to add to the carbonyl carbon (1,2-addition).

- Gilman reagents (organocuprates) are soft nucleophiles — they favor 1,4-conjugate addition to the β-carbon.

Gilman reagent is not the only nucleophile that does 1,4-additions to unsaturated compounds. It is a characteristic reaction of relatively weak nucleophiles such as halides, cyanide ion, thiols, alcohol, and amines:

Overall, these are called Michael addition reactions, and we discussed them in more detail here.

This behavior is explained by the Hard and Soft Acids and Bases (HSAB) principle. A simple way to think about it:

- Hard nucleophiles like RMgX and RLi are small, strongly charged, and less polarizable. They tend to react with hard electrophiles like carbonyl carbons.

- Soft nucleophiles like R₂CuLi are more polarizable and milder, and they prefer softer, delocalized electrophilic centers like the β-carbon in enones.

It’s also important to note that in conjugate addition reactions with organocuprates, the electron-withdrawing group doesn’t have to be a carbonyl. Other groups, such as nitriles (-C≡N), nitro groups (-NO₂), and sulfones (-SO₂R) can also activate the β-carbon for 1,4-addition.

The Reactions of Grignard and Organolithium, and Gilman Reagents with Epoxides

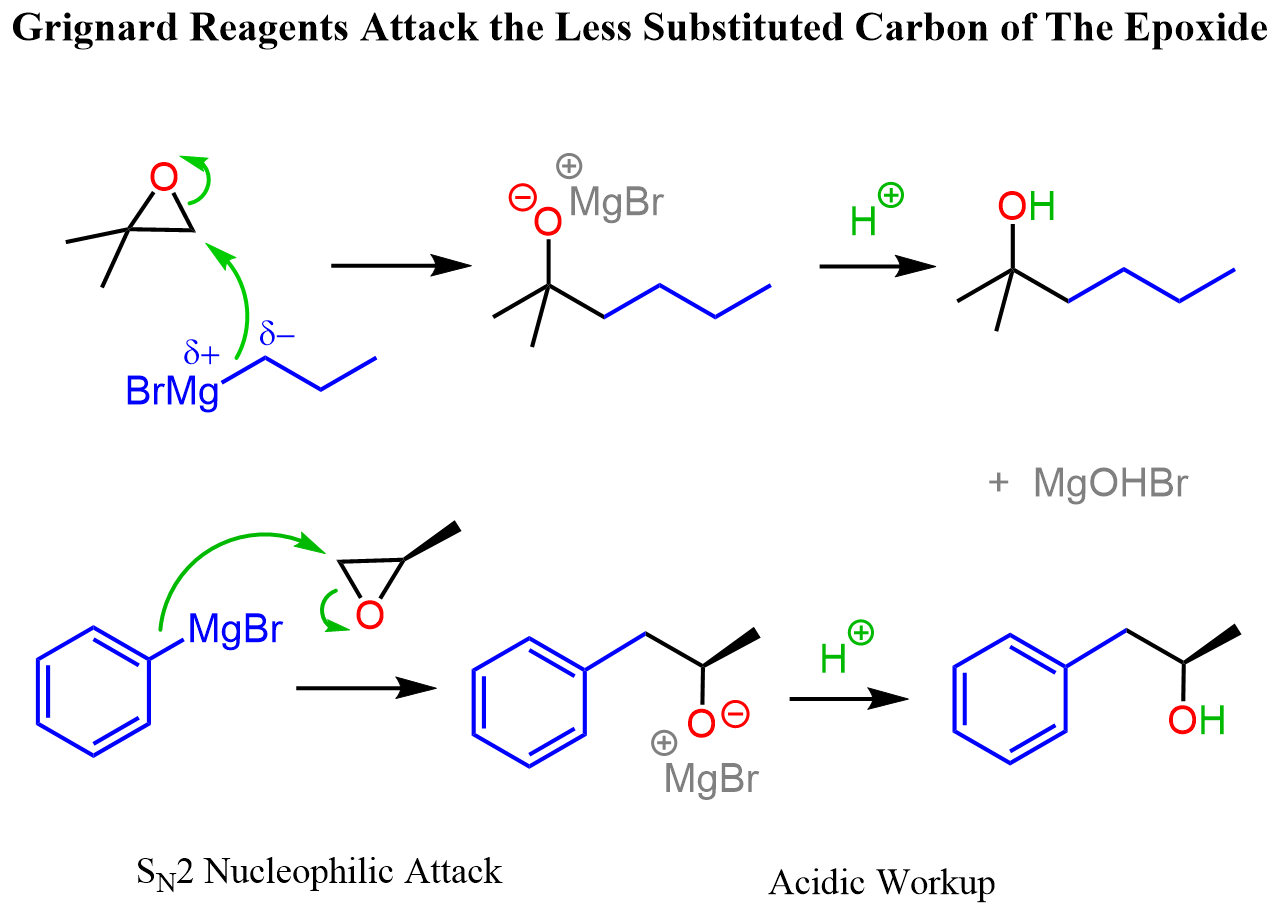

Grignard and organolithium reagents are great nucleophiles and strong bases, therefore, they attack epoxides at the less-substituted carbon atom. Overall, the addition of Grignard reagents to epoxides is a two-step process through which an alcohol is formed. In the first step, the epoxide ring is attacked at the least substituted carbon atom, forming an alkoxide intermediate, which is then treated with water or acidic workup to give the final product alcohol:

Check this article for more details on the reactions of Grignard reagents with epoxides.

Although organocuprates are not as nucleophilic, they still open up the epoxide ring by an SN2 mechanism like other strong nucleophiles do:

Carboxylic Acid Formation via Reaction with CO₂

Another common reaction of Grignard and organolithium reagents is their carboxylation with carbon dioxide. In this process, the organometallic compound acts as a nucleophile and attacks the electrophilic carbon in CO₂. The result is a carboxylate salt, which is then protonated during aqueous work-up to give a carboxylic acid.

This is a useful method for extending a carbon chain by one carbon and introducing a new functional group.

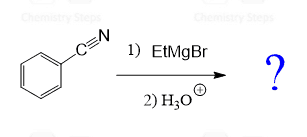

Reactions of Nitriles with Grignard and Organolithium Reagents

Grignard and organolithium reagents both react readily with nitriles to form ketones after acidic work-up. The reaction begins with nucleophilic attack of the organometallic reagent on the electrophilic carbon of the nitrile group, producing an imine intermediate. Upon hydrolysis, this intermediate is converted into the corresponding ketone.

Check this post for the mechanism of converting nitriles to ketones.

Unique Reactivity of Organolithium Reagents with Carboxylic Acids: Formation of Ketones

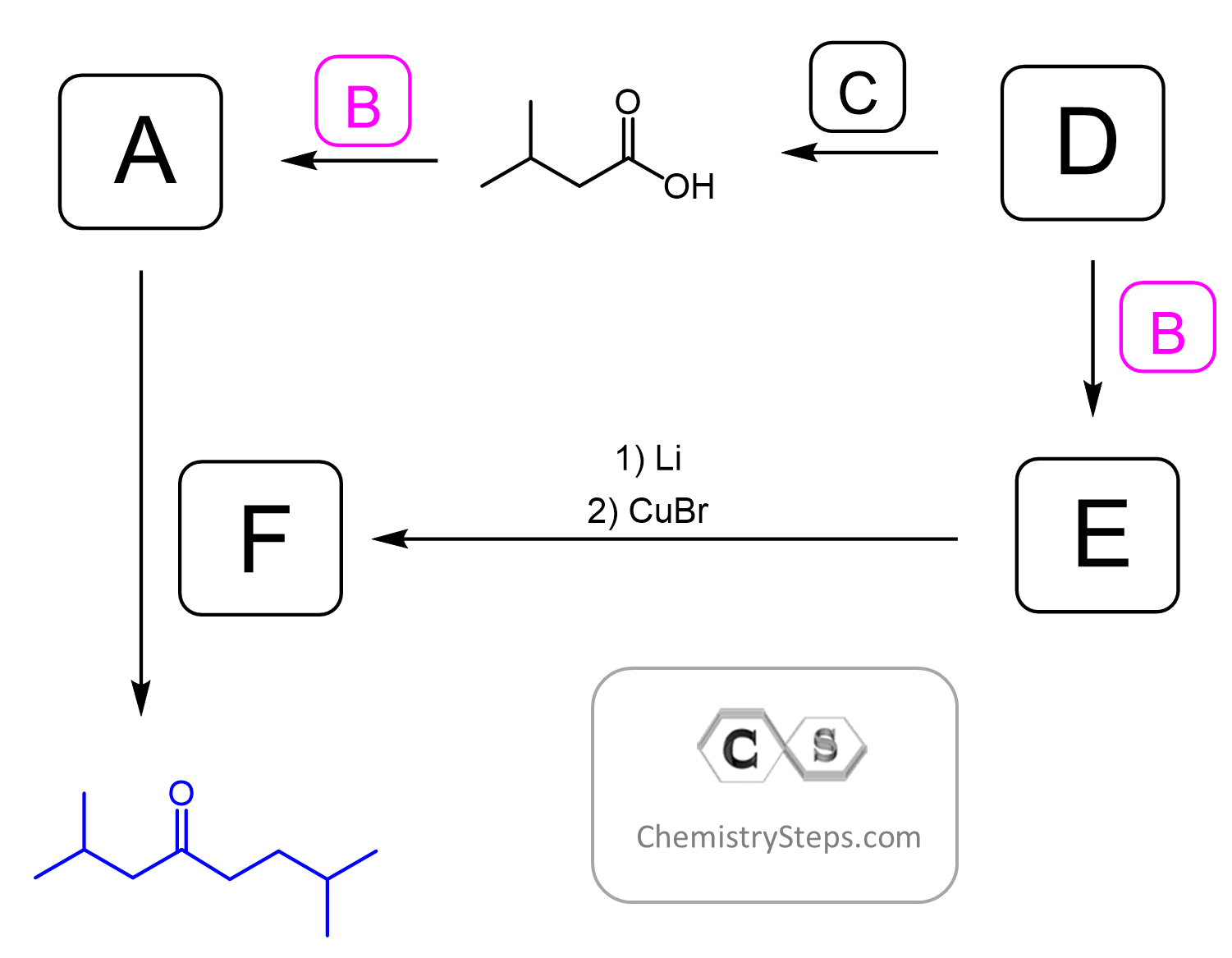

What is unique about organolithium reagents compared to Grignard reagents is their greater basicity and nucleophilicity, which enables them to react with carboxylic acids to form ketones. Initially, the organolithium deprotonates the carboxylic acid, generating a lithium carboxylate intermediate. Then, a second equivalent of the organolithium attacks the carbonyl carbon of this intermediate, leading to ketone formation after elimination of the leaving group.

In contrast, Grignard reagents are less reactive and usually get quenched by the acidic proton of carboxylic acids before any useful reaction can occur. Gilman reagents (organocuprates) are even less reactive toward carboxylic acids and generally do not react. Thus, organolithiums uniquely provide a synthetic route to convert carboxylic acids into ketones that is not accessible with Grignard or Gilman reagents.

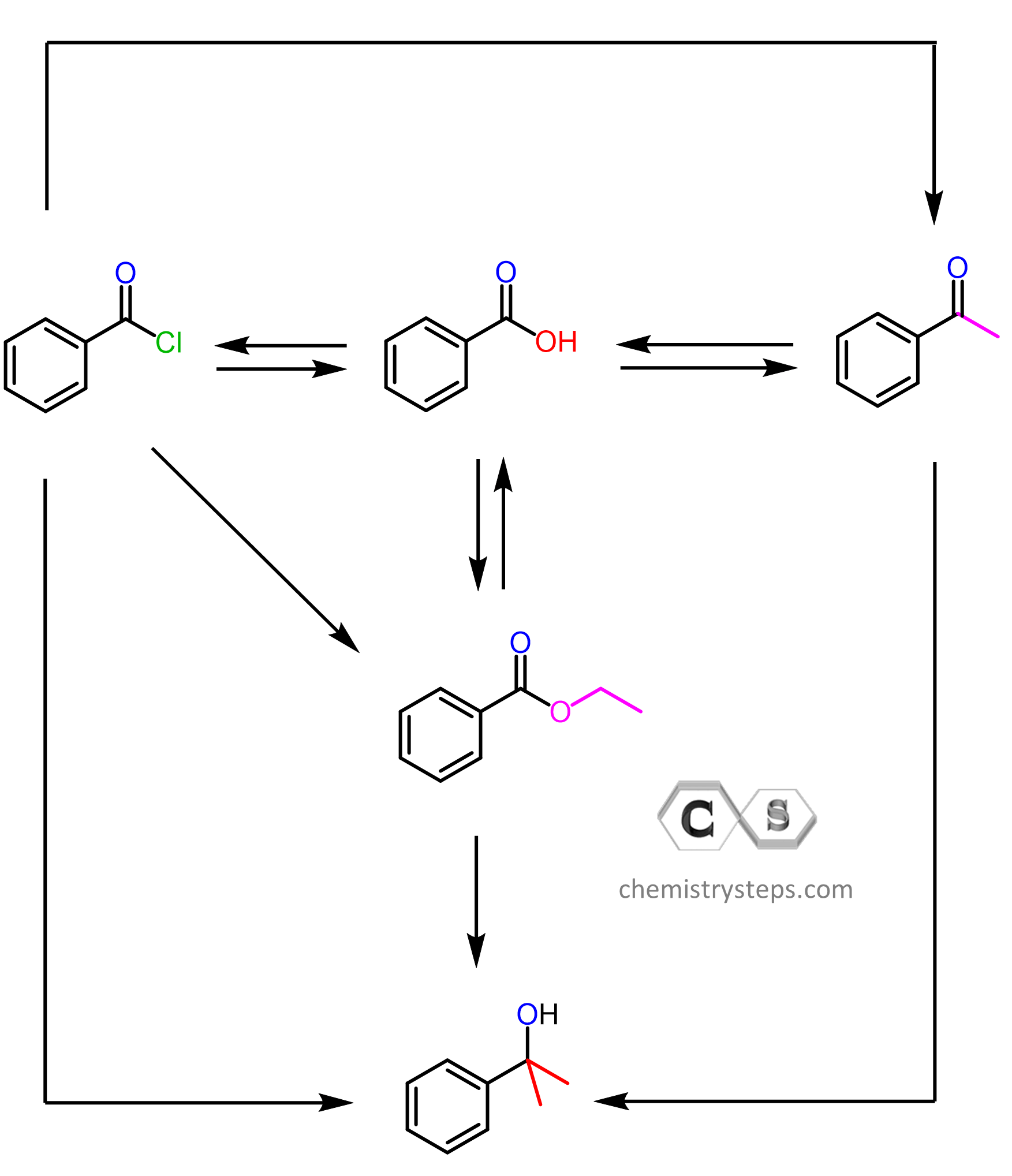

Summarizing the Reactions of Grignard, Organolithium, and Gilman Reagents

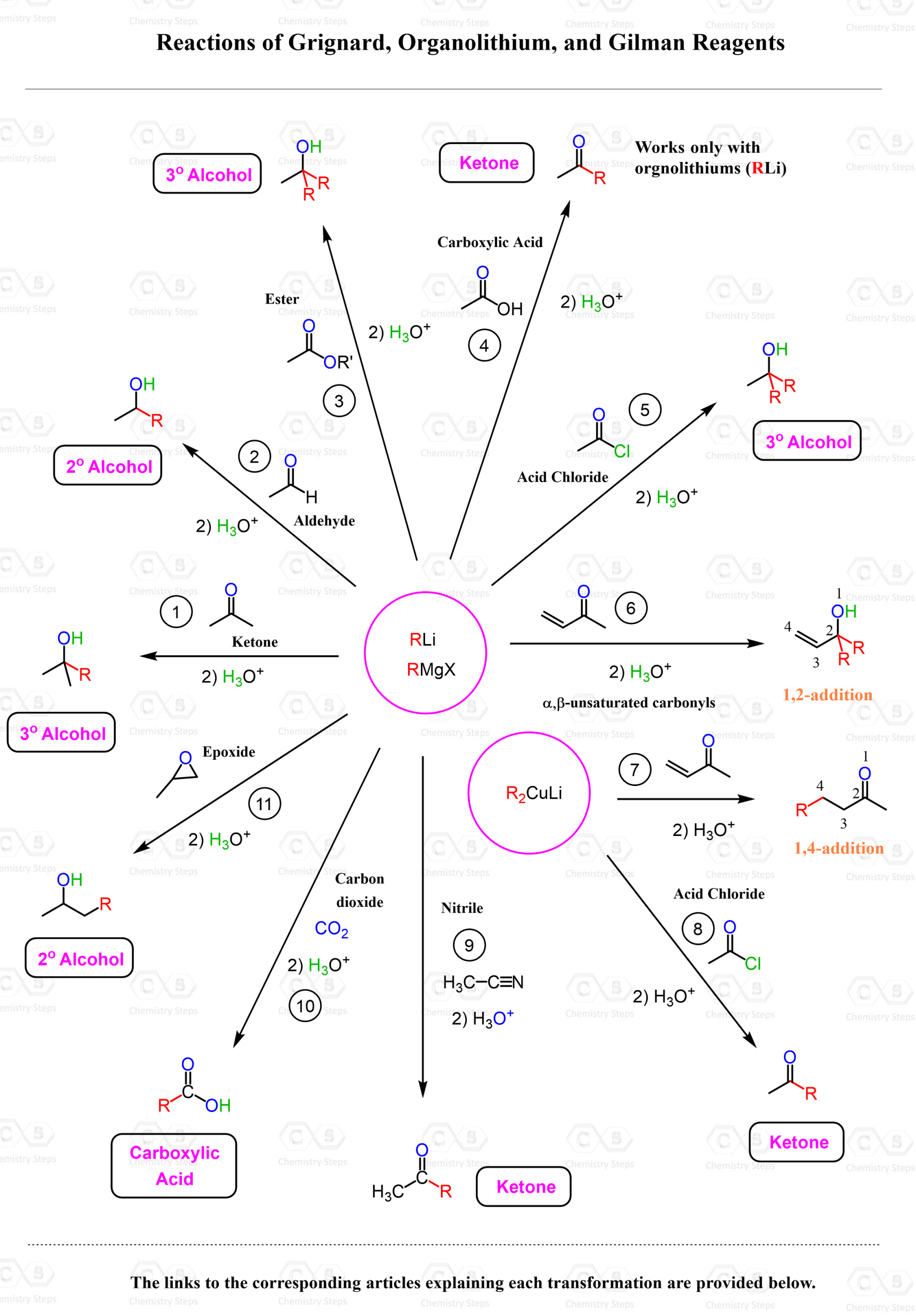

The chart below summarizes the reactivity of Grignard, organolithium, and organocuprate reagents with various electrophiles — including aldehydes, ketones, esters, acid chlorides, nitriles, α,β-unsaturated carbonyls, CO₂, and epoxides:

- Grignard, organolithium, and Gilman (organocuprate) reagents are all organometallic compounds that act as strong nucleophiles due to their polar carbon–metal bonds. While they share similar structures, their reactivity patterns differ significantly.

- Grignard and organolithium reagents are highly reactive and add to the carbonyl carbon of aldehydes and ketones to form secondary and tertiary alcohols via 1,2-addition. When reacted with esters, they add twice to give tertiary alcohols. They can also convert acid chlorides to ketones, but usually continue reacting unless controlled.

- In contrast, Gilman reagents are softer nucleophiles. They typically do not react with aldehydes, ketones, or esters. Instead, they react selectively with acid chlorides, stopping at the ketone stage, and add to the β-position of α,β-unsaturated carbonyls via 1,4-conjugate addition.

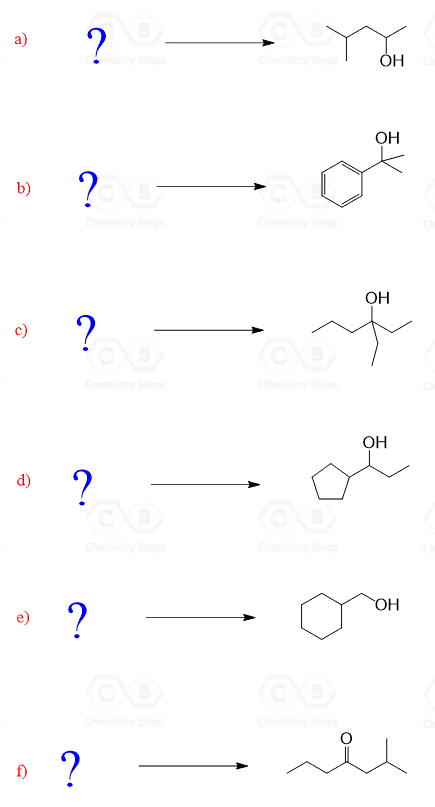

1, 2) Reactions of Grignard Reagents with Aldehydes and Ketones

Grignard reagents react with aldehydes and ketones via nucleophilic addition to the carbonyl carbon, forming alcohols after acidic work-up. Reaction with an aldehyde gives a secondary alcohol, while reaction with a ketone gives a tertiary alcohol. This is a classic and reliable method for building carbon–carbon bonds and forming alcohols in organic synthesis.

3) Grignard reagents react with esters in a two-step nucleophilic addition process to give tertiary alcohols. The first equivalent of the Grignard reagent adds to the ester, forming a ketone intermediate, which is more reactive and quickly undergoes a second addition with another equivalent of the Grignard. After acidic work-up, the final product is a tertiary alcohol with two identical alkyl groups added to the original ester carbon.

4) Carboxylic Acids to Ketones

- Organolithiums are extremely powerful bases and nucleophiles capable of adding to the carboxylate ion. This addition forms a tetrahedral dianion intermediate, which lacks a relatively good leaving group and stays in the solution until water is added to hydrolyze it to the corresponding ketone.

5) Acid Chlorides with Grignard and Organolithium Reagents

- Acid chlorides react with Grignard or organolithium reagents to form tertiary alcohols after two additions. The carbonyl is first converted to a ketone, then attacked again to give the final alcohol product. Careful control of using Gilman reagents (organocuprates) can stop at the ketone stage.

6, 7) Reaction of Grignard, Organolithium, and Gilman Reagents with α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds

- Grignard and organolithium reagents typically undergo 1,2-addition to the carbonyl carbon, while Gilman reagents (organocuprates) prefer 1,4-conjugate addition to the β-carbon due to their softer nucleophilic character.

- Acid chlorides react with organocuprates (Gilman reagents, R₂CuLi) to give ketones via selective acyl substitution. Unlike Grignard or organolithium reagents, which add twice to form tertiary alcohols, organocuprates add only once, making them ideal for synthesizing ketones without overreaction.

9) The Reaction of Grignard, Organolithium Reagents with Nitriles

- We can convert nitriles to ketones by reacting the nitrile with a Grignard reagent or an organolithium reagent. This adds an alkyl group to the nitrile carbon, forming an intermediate imine magnesium or lithium salt, which upon acidic hydrolysis yields the ketone.

10) Alkyl halides can be converted into carboxylic acids by forming a Grignard reagent, reacting it with CO₂, and then performing an acid workup. While the full scope of Grignard chemistry goes beyond this, the transformation is a useful functional group conversion to keep in mind.

11) Reaction of Grignard, Organolithium, and Gilman Reagents with Epoxides

- Grignard and organolithium reagents open epoxides via nucleophilic attack at the less substituted carbon, forming alcohols after protonation. Gilman reagents generally do not react with epoxides.

All the transformations described above are from the reactions of aldehydes, ketones, esters, acid chlorides, nitriles, and α,β-unsaturated compounds. These and many more are included in our Organic Reaction Maps. These maps are a great resource for students preparing for exams, reviewing synthesis strategies, and understanding how different functional groups interconvert. If you’re ever unsure how to go from one molecule to another, the maps can guide you through the process clearly and visually.

Excellent

How to convert crotonaldehyde to 2,3-dimethyl butanal

Thank you. Double alkylation with a Gilman and a methyl iodide would probably do.