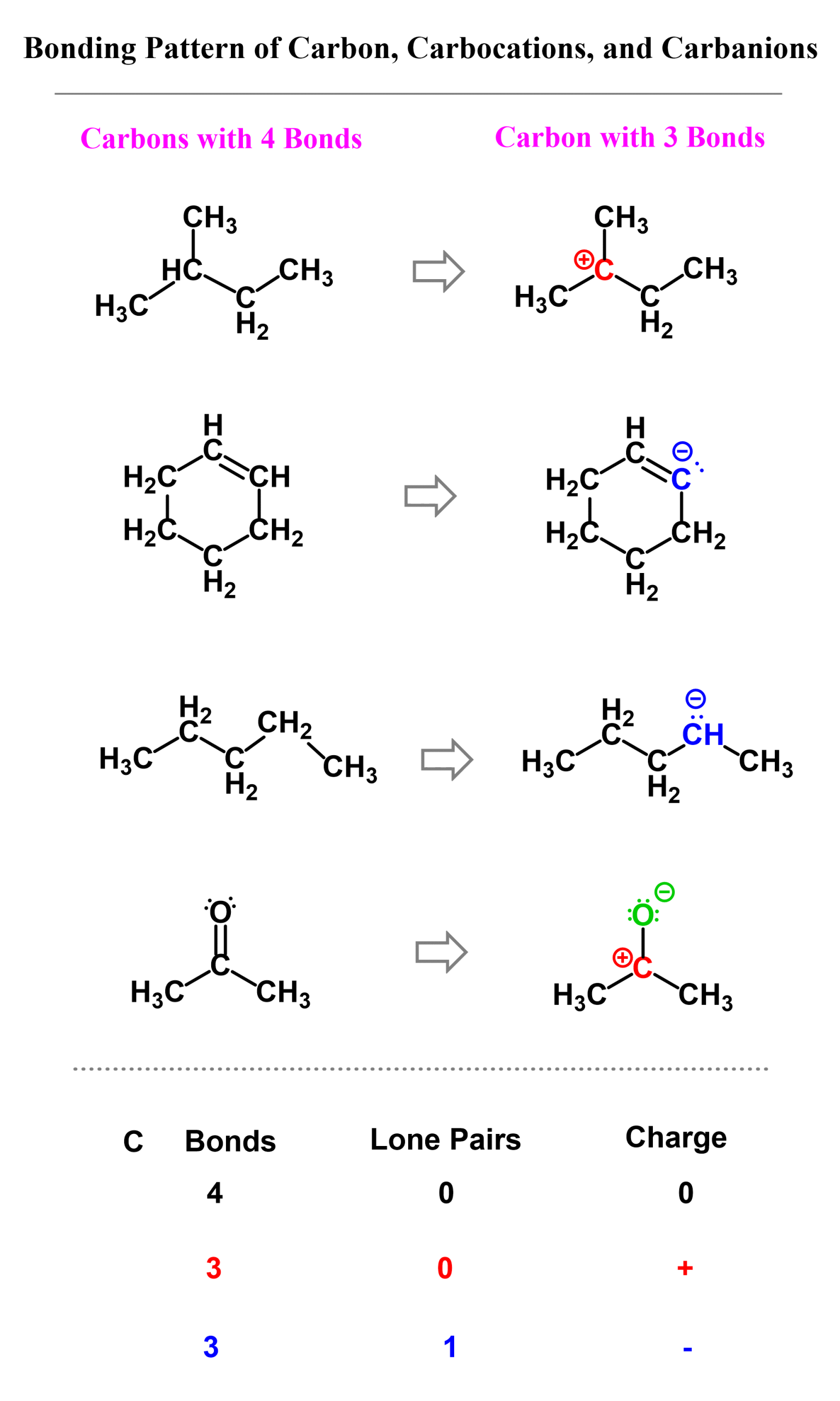

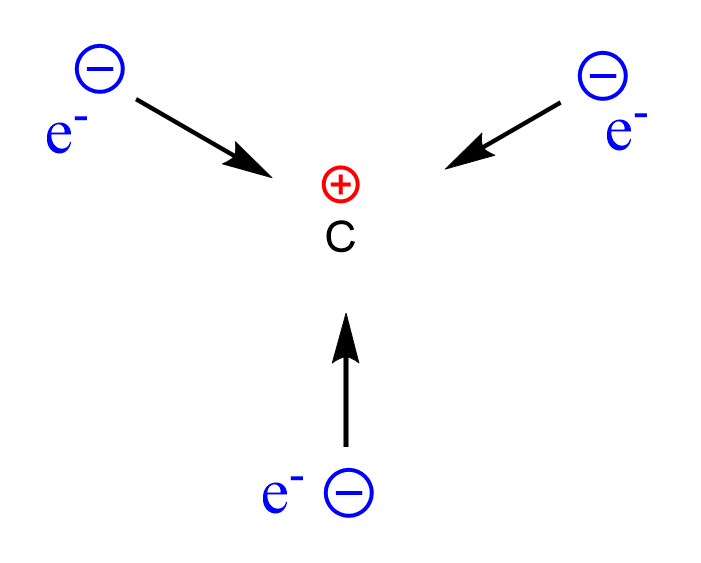

Carbocations are electron-deficient species, as the carbon atom is surrounded by only three bonds with no lone pairs. Remember, the standard bonding pattern of carbon is 4 bonds with no lone pair:

So, how can we stabilize the positive charge? Even if you hate organic chemistry, the natural answer to this question is to provide some negative charge. The negative charge in chemistry is provided by electrons, so we need some groups or atoms that would push electrons towards the positive charge to balance it as much as they can.

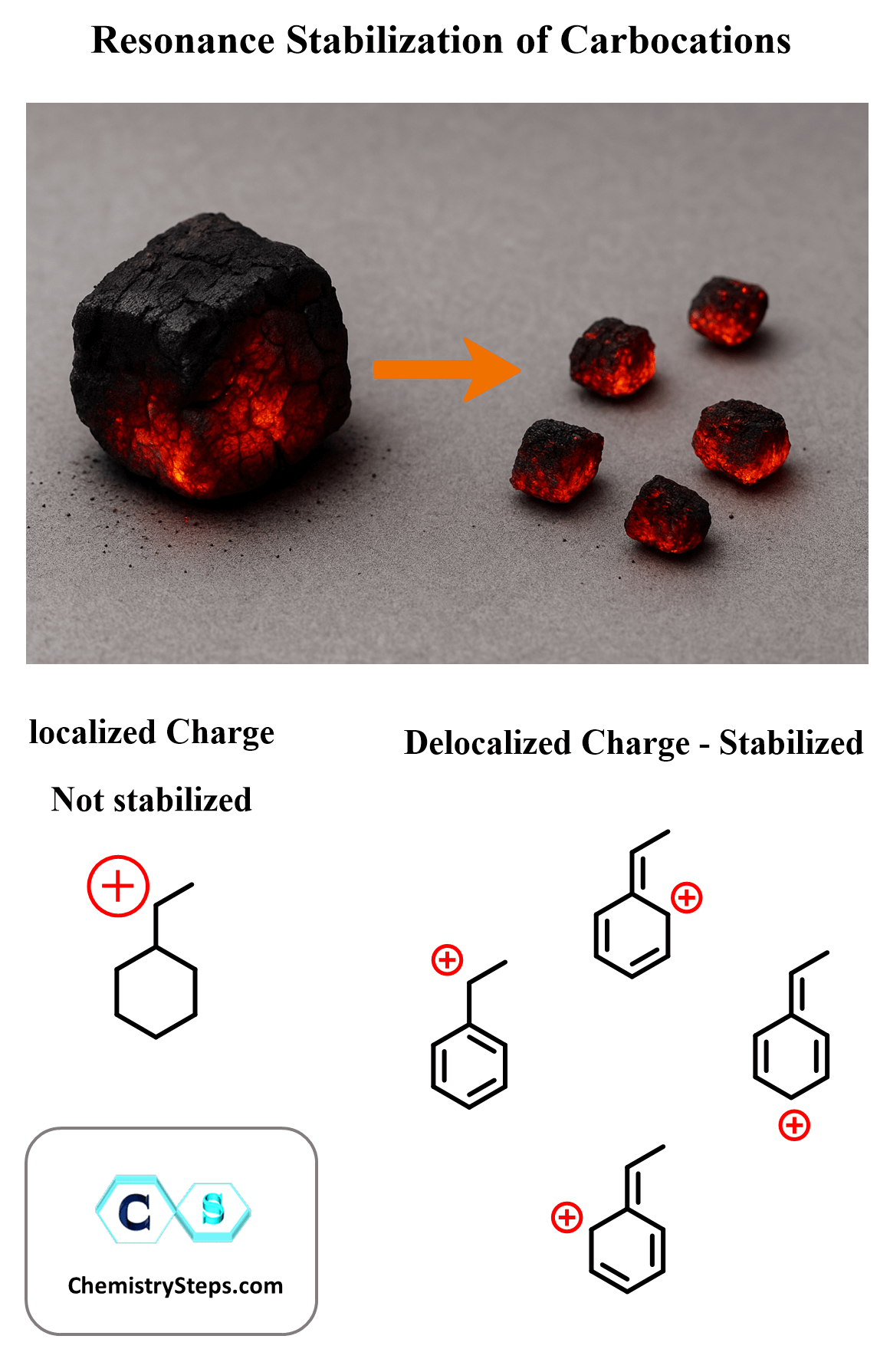

Another way of dealing with this is breaking the positive charge into pieces and spreading them around. Think of a carbocation like a single burning coal – intensely hot and unstable, concentrating all the energy (or in chemistry terms, the positive charge) in one place. Now imagine breaking that coal into several glowing pieces and spreading them out. The heat is still there, but it’s distributed more evenly across space, making the system less intense and more stable overall.

This is exactly what happens in resonance stabilization: the positive charge of the carbocation is not stuck on a single atom, but delocalized over multiple atoms through resonance structures. Just like spreading the heat prevents one coal from burning out too fast, resonance prevents any one atom from bearing the full burden of the positive charge.

Ok, let’s now see how we can suppress or break down the positive charge chemically. For this, we need electron-donating groups, which can be either inductive or resonance donators. Check out this article on the Inductive and Resonance Effects to refresh these concepts. In short, the inductive effect is the pushing or pulling electron density through single bonds, whereas the resonance effect is the same principle achieved with the help of lone pairs or pi bonds.

Let’s start with the inductive Effect

Alkyl Groups and Carbocation Stability

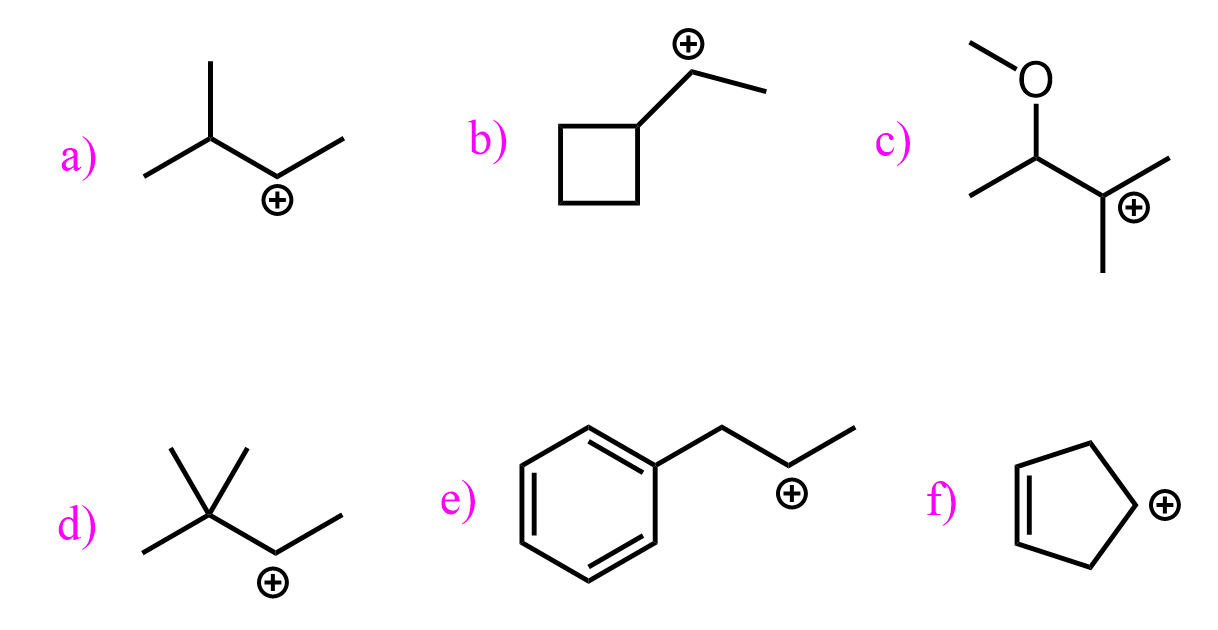

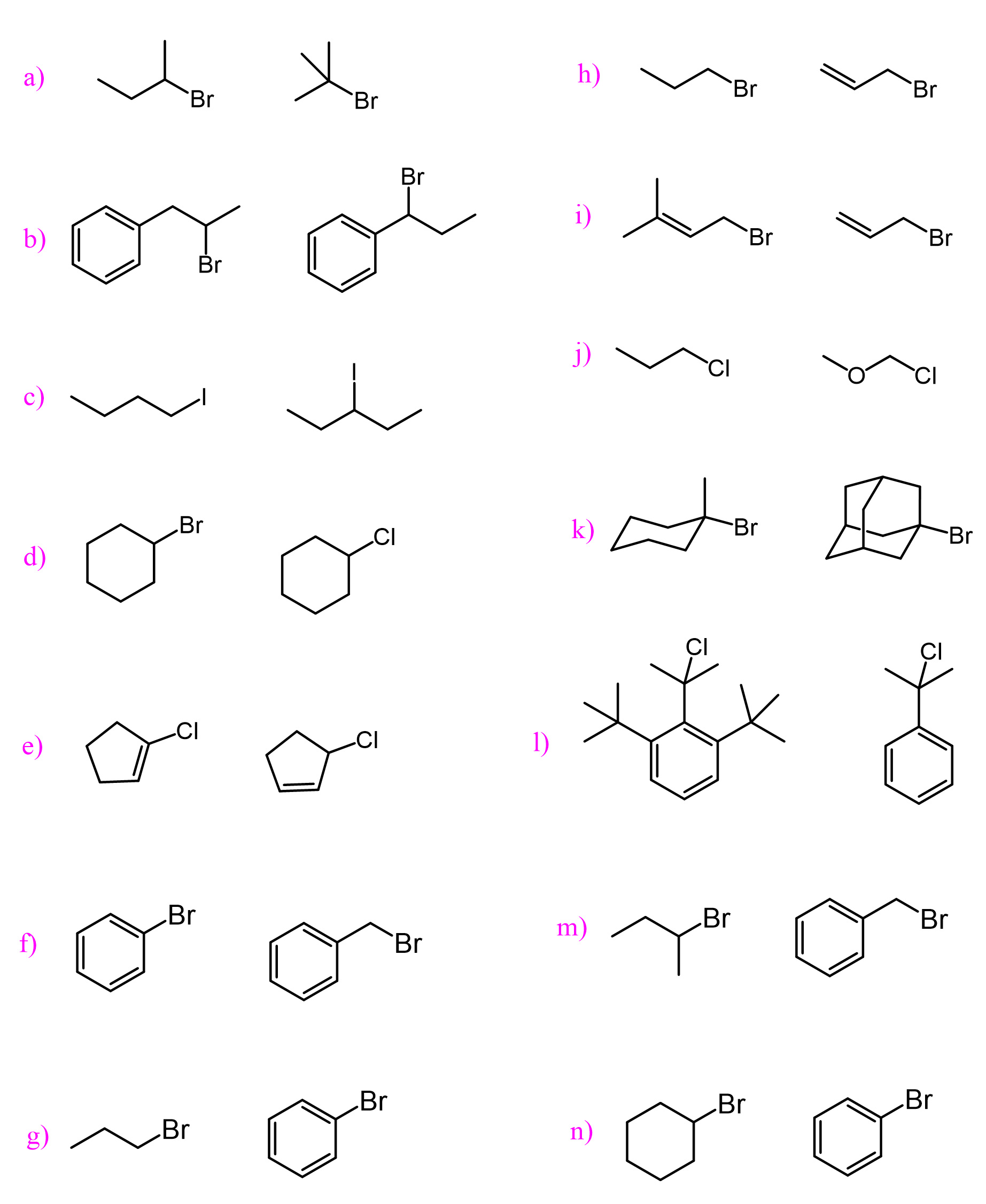

Alkyl groups are electron-donating groups (EDG) via the inductive effect, so the more of them we have on the positively charged carbon, the more stable the carbocation becomes. Therefore, tertiary alkyl halides are more stable than secondary and primary alkyl halides.

Another way alkyl groups stabilize the positively charged carbon atom is through hyperconjugation. Hyperconjugation is the charge-stabilization by pushing some electron density of the adjacent σ bond to the empty p orbital of the carbocation:

The more alkyl groups, the more C-H bonds donate electron density to the empty p orbital of the carbocation, making it more stable.

It does not have to be a C-H bond, but what is important is that the sp2 orbital is parallel with the electron-donating sigma bond. We can see this when comparing conjugated and isolated dienes (two bonds). The overlapping p orbitals on adjacent atoms allow the electrons of conjugated pi bonds to be delocalized over four or more atoms:

On the contrary, the delocalization breaks when p orbitals are separated by and sp3-hybridized carbon because it does not have an unhybridized p orbital capable of participating in the electron flow.

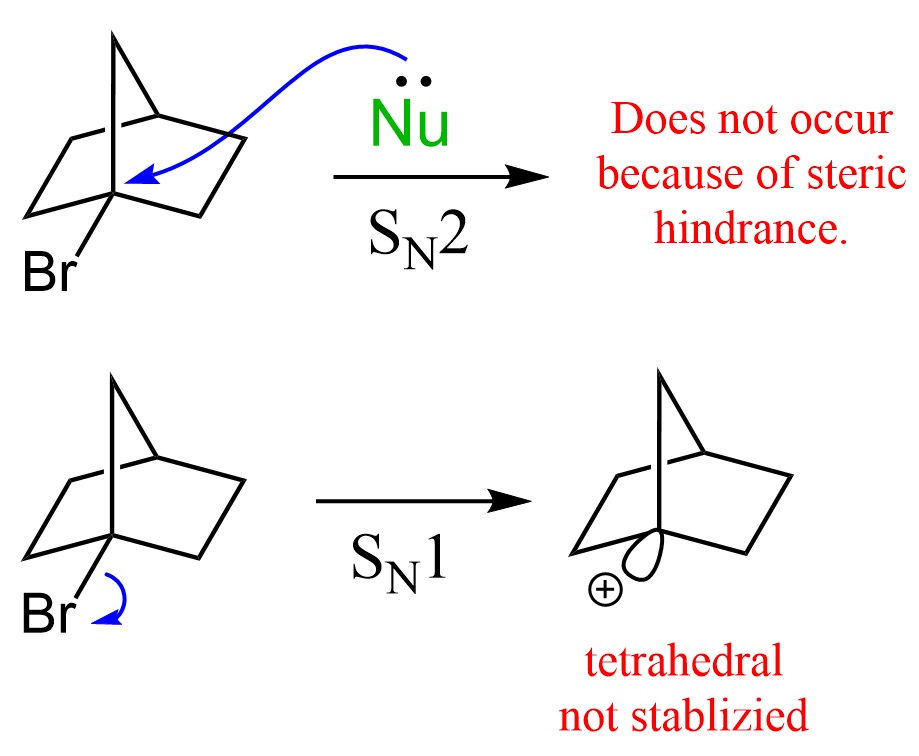

A great example illustrating this is the unreactive nature of bicyclic alkyl halides, where the carbon connected to the halogen is locked in a tetrahedral geometry. This means that it cannot be planar and thus stabilized by neighboring alkyl groups. For example, the following bicyclic alkyl halide does not react either by the SN1 (for the reasons we just mentioned) or SN2 mechanism because of the steric hindrance:

With these principles in mind, let’s now discuss the reactivity of carbocations

Carbocations and Reactivity of Alkyl Halides

You may have already covered in class that tertiary alkyl halides undergo SN1 and E1 reactions while primary alkyl halides undergo SN2 and E2 reactions. Check the article “Deciding Between SN1, E1, SN2 and E2 Reactions” to refresh or learn these patterns.

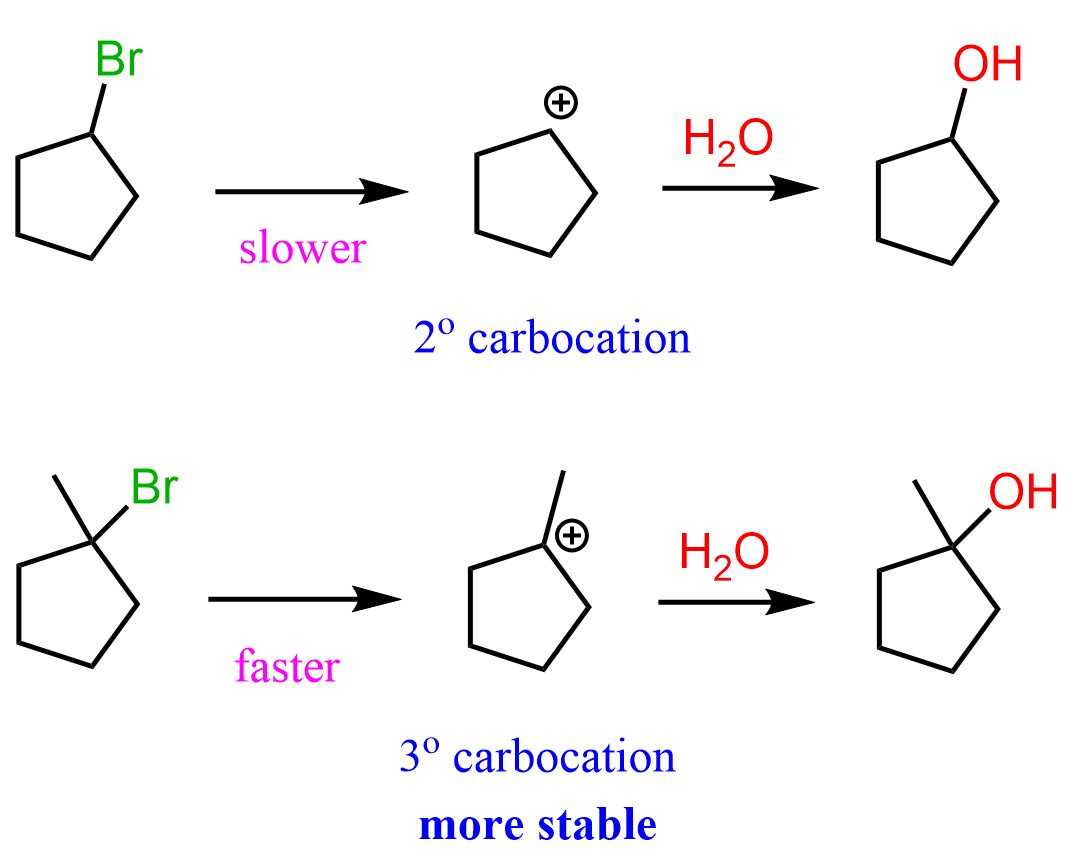

For now, we will only briefly mention that the reason for this is that the SN1 and E1 reactions are unimolecular mechanisms and proceed via the formation of carbocations. Importantly, this is the rate-determining step of these reactions, and the more stable the carbocation, the faster they occur. For example, tertiary alkyl halides can be hydrolyzed more easily than secondary alkyl halides because the corresponding tertiary carbocation, formed in the first step, is more stable.

The same is true for E1 reactions – the more stable the intermediate carbocation, the faster the reaction. Remember, most often the E1 and SN1 reactions are competing, and a mixture is obtained:

Heat and formation of substituted alkenes are generally used to favor the E1 path.

Once again, primary alkyl halides do not undergo SN1 or E1 reactions because they are too unstable to form.

Resonance Stabilization of Carbocations

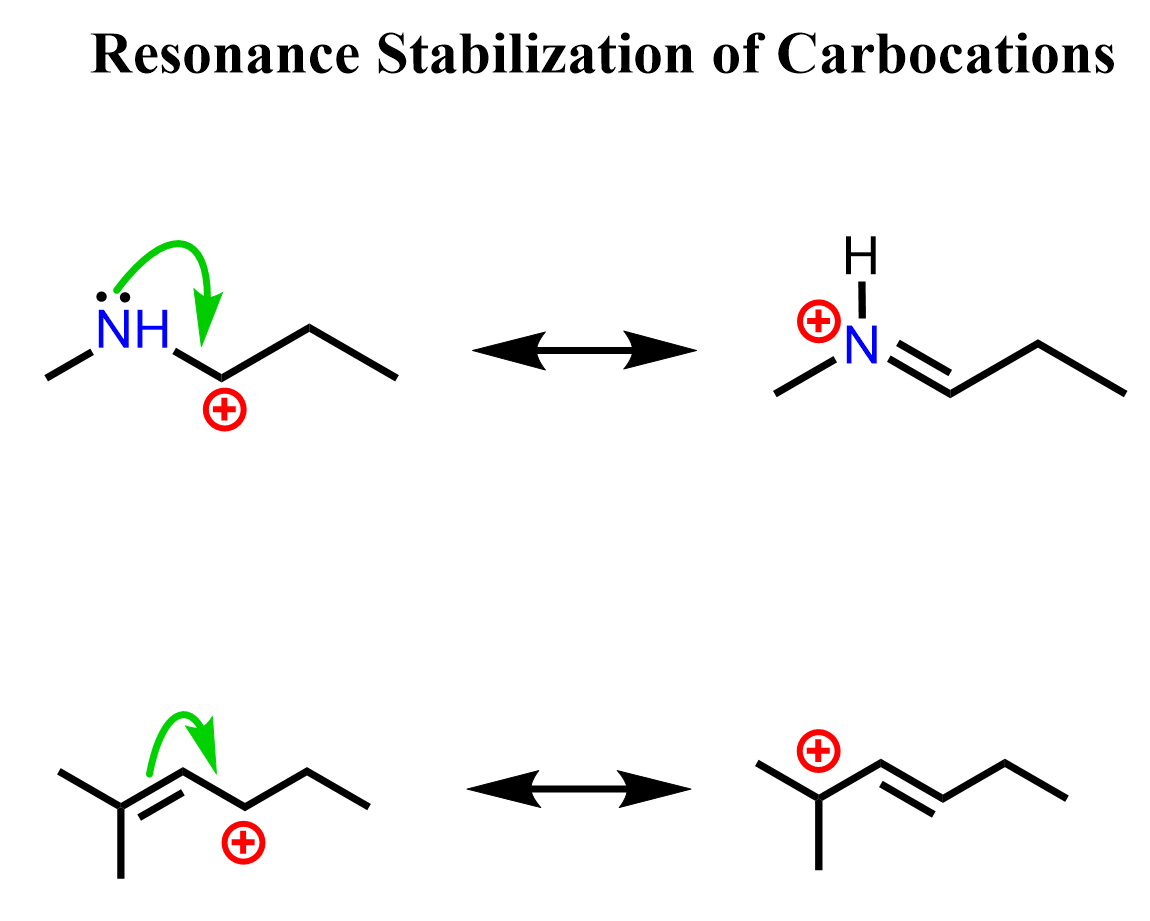

To understand how resonance affects the stability of carbocations, make sure you remember the principle of localized and delocalized electrons mentioned at the beginning of the semester. In short, delocalized electrons are those that can participate in resonance transformations.

If there is an atom with lone pairs next to the positively-charged carbon atom, it can donate one of the lone pairs to the empty p orbital, thus fulfilling the octet of the carbon. Remember, a complete octet stabilizes the molecule. This can also be electrons of a pi bond. For example, see how the electrons of nitrogen and the pi bond can stabilize an adjacent carbocation:

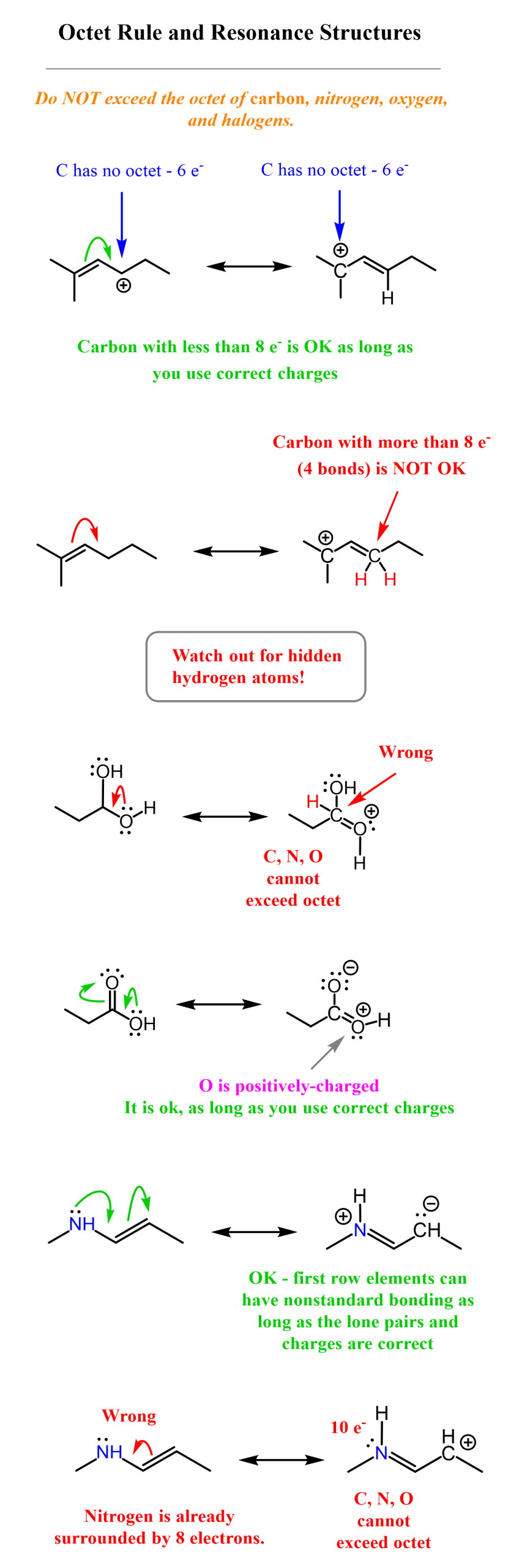

To identify and draw the correct resonance stabilization of carbocations, you need to know the rules for drawing resonance structures. This is mainly about not exceeding the octet on carbon and other second-row elements, and not breaking or making single bonds when drawing resonance forms. Here are some examples of correct and incorrect resonance transformations, and you can check the linked article for more details.

Benzylic Carbocations

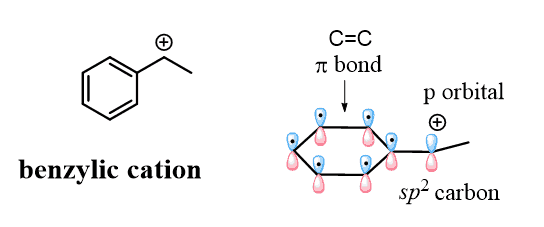

Resonance stabilization is the reason why benzylic halides are very reactive in SN1 and E1 reactions. The pi electrons of the ring delocalize the charge from the carbon atom, thus stabilizing it, making the rate-determining step of these reactions faster.

Notice that benzylic halides are also very reactive in SN2 and E2 reactions, and SN1 and E1 reactions occur only if weak nucleophiles and bases are used.

The carbocations are sp2-hybridized, and the empty p orbital of the positively charged carbon is nicely aligned with the p orbitals of the aromatic system, which makes the cation resonance-stabilized:

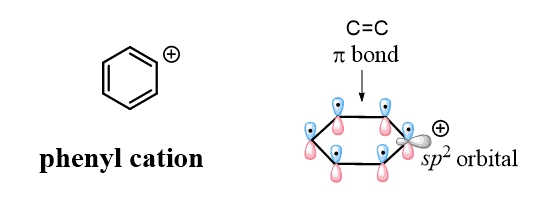

Don’t confuse the benzylic carbocation with the phenyl carbocation. Yes, they are both sp2 carbons, but unlike the benzylic carbon, the positive charge of the phenyl cation is a result of the empty sp2 orbital, which lies perpendicular to the conjugated aromatic system and cannot be resonance stabilized:

This is the reason, for example, why aryl and vinyl halides do undergo SN1, E1, and Finkelstein-Crafts alkylation (Organic 2 topic) reactions:

To bring all types of carbocations together, you can memorize (it’s fairly intuitive, though) the following pattern of carbocation stability:

Methyl < Primary < Secondary < Tertiary < Allylic ≈ Benzylic

Carbocation Stability and Rearrangement Reactions

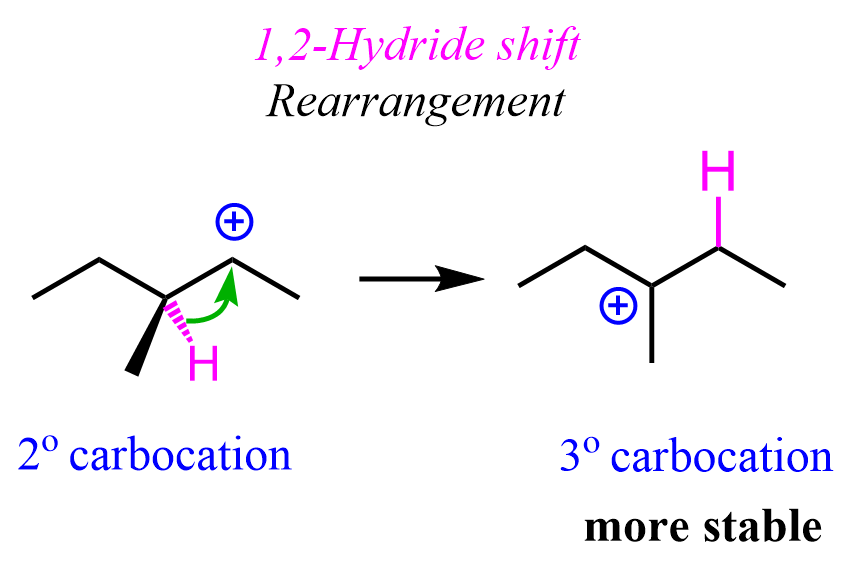

Because less substituted carbocations are less stable than more substituted ones, they tend to undergo rearrangements to become better stabilized. These are either hydride shifts, methyl shifts, or ring-expansion rearrangements.

This is often an undesirable outcome, as it makes the product unpredictable and, in the case of chiral substrates, results in the loss of chirality.

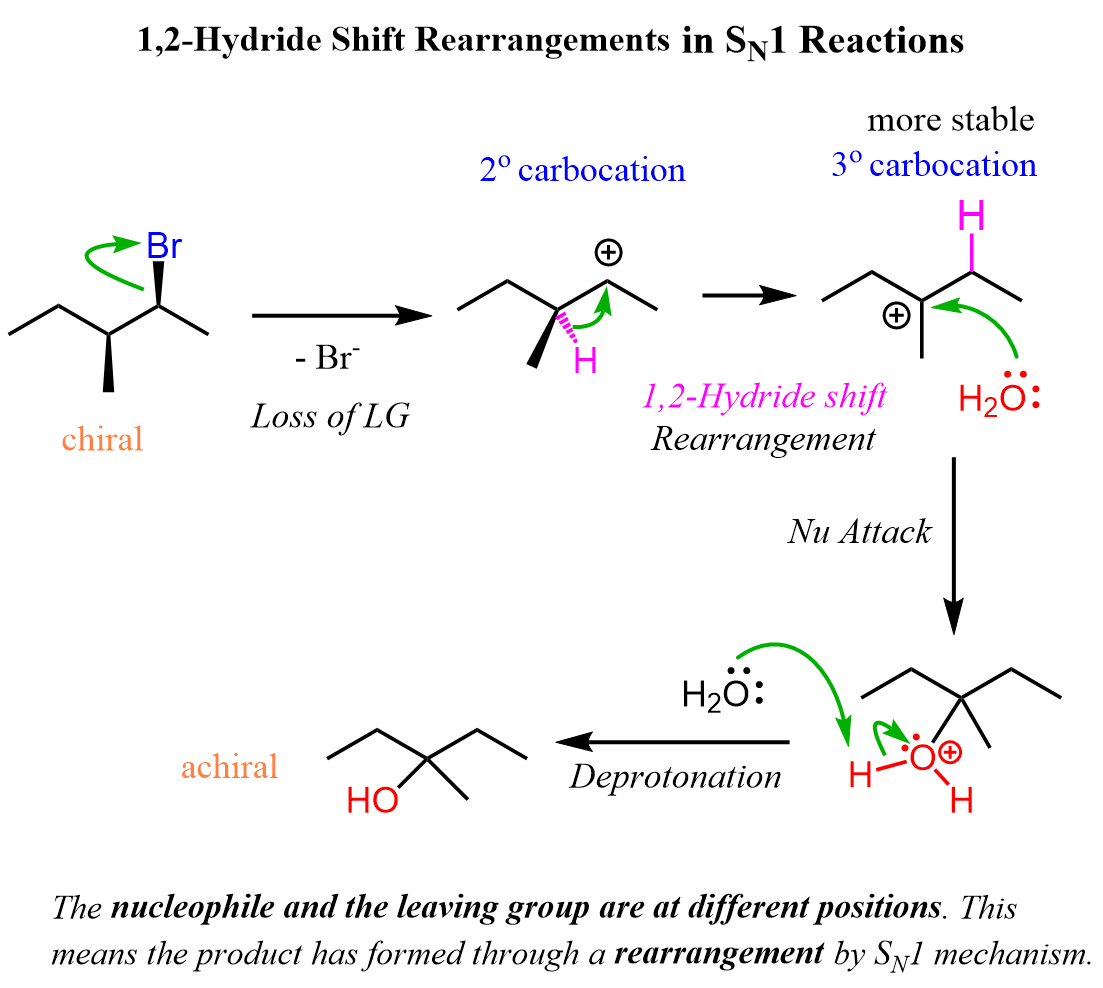

For example, the following chiral alkyl halide gives a rearrangement product as a result of the secondary carbocation rearranging into a tertiary carbocation:

Notice that the chirality of the middle carbon is lost upon the hydride shift because carbocations are sp2-hybridized and only have three atoms connected to the positively charged carbon. Because of symmetrical structures, the nucleophilic attack of water produces an achiral alcohol. There can be other stereochemical outcomes of SN1 reactions, and we cover that in a dedicated post, which you can find here.

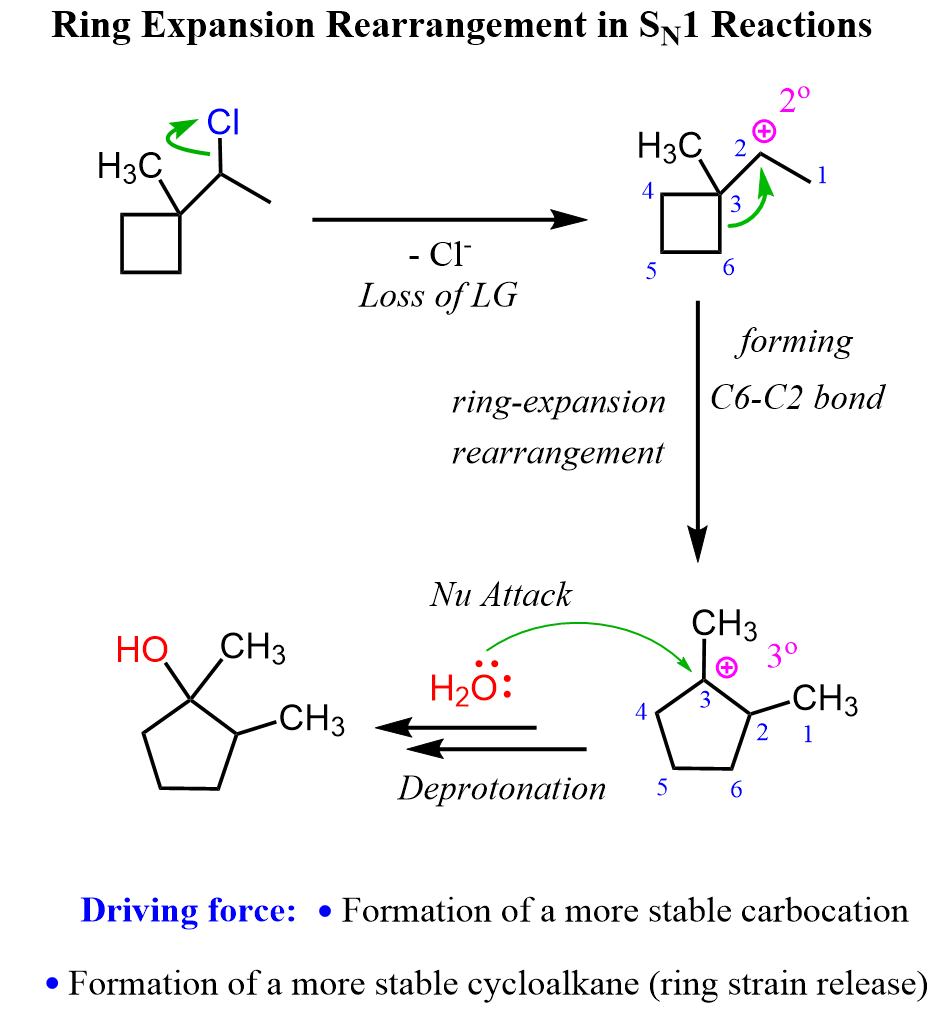

Ring Expansion Rearrangements in SN1 Reactions

A common type of carbocation rearrangement is the ring expansion of 4 or 5-membered cycloalkanes. The driving force in these reactions is both the increased stability of carbocations (2o-3 o) and the ring itself. Remember, a 4-membered ring has quite a high ring strain, which is released when expanded to a 5-membered ring. Reaction 8 is an example of ring-expansion rearrangement in an SN1 reaction:

For cyclopentanes, even though they are very stable molecules, they are still associated with a little ring strain. This, combined with the possibility of rearrangement from secondary to tertiary carbocation, facilitates the ring expansion rearrangement of 5-membered rings to cyclohexenes.

Rearrangements in Alkene Addition Reactions

You may not have started the chapter on alkenes, so feel free to skip this section and focus more on the substitution and elimination reactions.

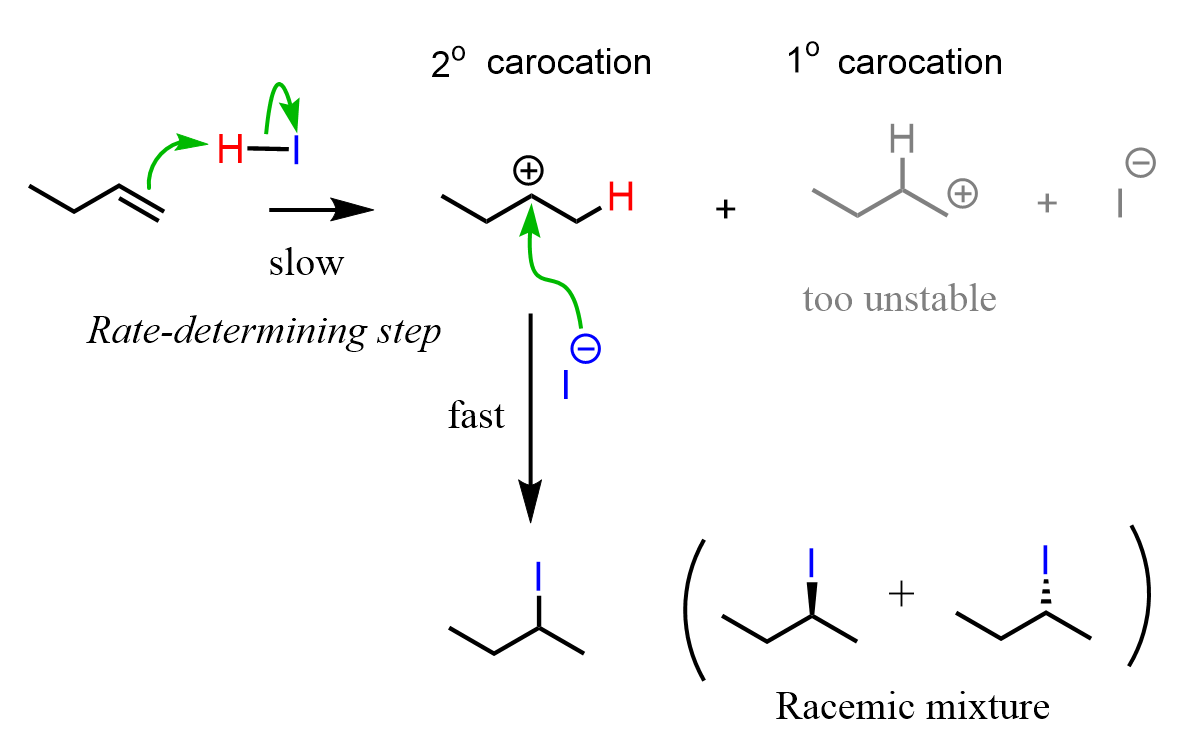

Formation of intermediate carbocations is also common in electrophilic addition reactions of alkenes. This lays the foundation for Markovnikov’s rule, which states that in addition reactions of alkenes, the hydrogen adds to the less substituted carbon of the alkene because that leads to the formation of a more substituted carbocation.

As a result of this hydrogen addition, the halogen ends up on the more substituted carbon of the double bond.

Like in the case of SN1 and E1 reactions, however, sometimes the product of these reactions is not what we expect.

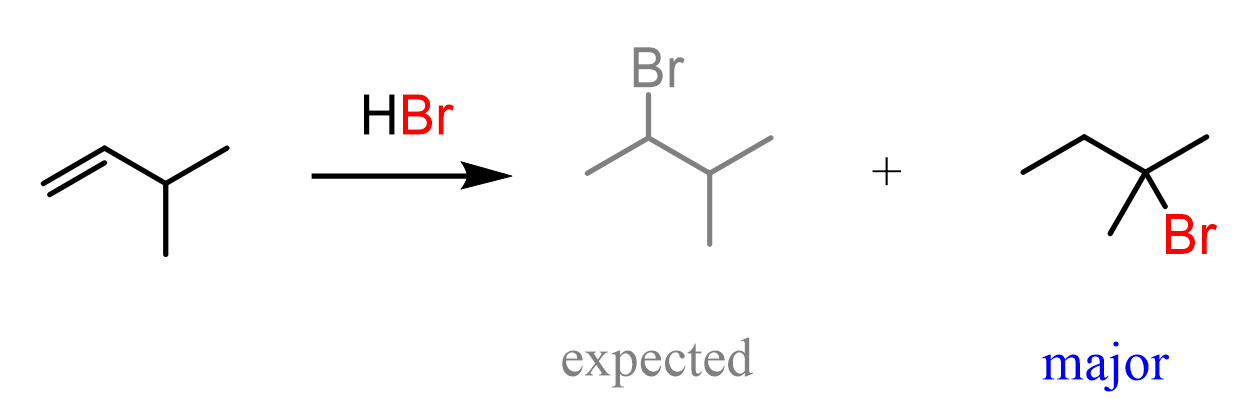

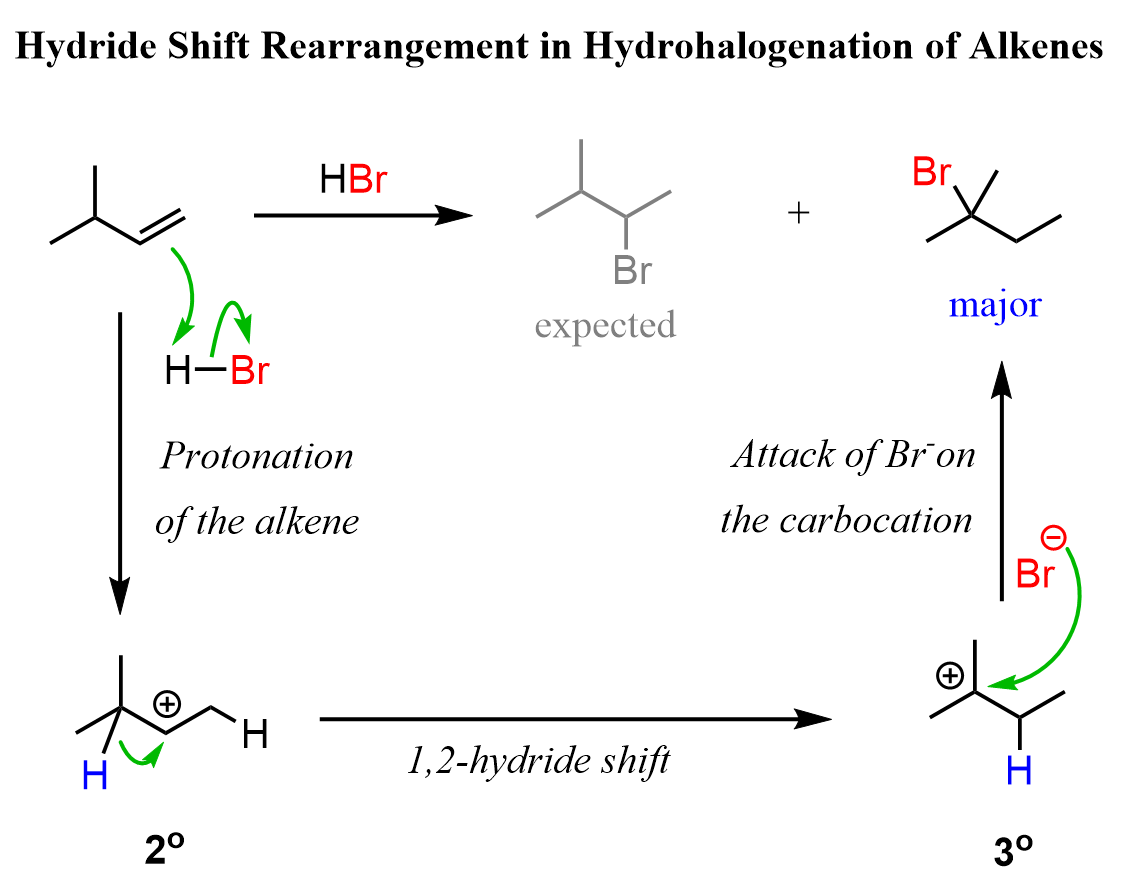

For example, when the following alkene is treated with HBr, based on Markovnikov’s rule, we might expect the Br to add to the middle carbon because it leads to the formation of a more stable secondary carbocation.

In the first step, we know that the hydrogen addition will form a secondary carbocation because it is more stable than the possible primary carbocation. This is true; upon protonation, the secondary carbocation is formed; however, before reacting with the bromide ion, it undergoes a 1,2-hydride shift rearrangement to form a more stable tertiary carbocation.

Once the tertiary carbocation is formed, it is attacked by the bromide, resulting in a tertiary alkyl halide as the major product of the reaction:

Check this article for more details and examples on Rearrangements in Alkene Addition Reactions.

To summarize,

Remember that carbocations are unstable, electron-deficient species, and their stability plays a crucial role in determining the rate and outcome of many organic reactions, such as SN1, E1, and electrophilic addition to alkenes.

- More substituted carbocations are more stable due to inductive, resonance effects, and hyperconjugation.

- Resonance stabilization can greatly enhance carbocation stability when lone pairs or pi bonds are available to delocalize the positive charge.

- Benzylic and allylic carbocations are especially stable due to resonance.

- When possible, carbocations rearrange (via hydride shifts, alkyl shifts, or ring expansions) to form more stable carbocations, which can lead to unexpected products.

- In alkene additions, Markovnikov’s rule applies because the intermediate carbocation forms on the more substituted carbon. However, rearrangements are possible, which can lead to unexpected products.

Keep these ideas in mind as you work through reaction mechanisms, and you’ll find predicting outcomes much easier.

Let me know in the comments if you have any questions.