In this post, we will talk about the E2 and E1 elimination reactions of substituted cyclohexanes. Let’s start with the E2 mechanism.

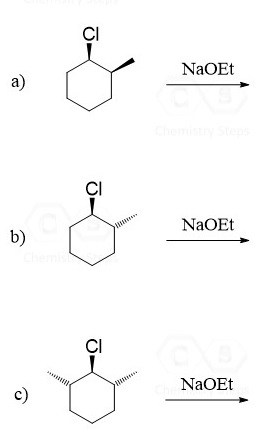

When the following substituted cyclohexane is treated with sodium ethoxide, an E2 elimination is expected to occur, as we have a strong base reacting with a secondary alkyl halide:

The elimination does occur; however, what is interesting is that the alkene is not the Zaitsev’s product:

Remember, the Zaitsev product is the more substituted alkene, and it is expected to be the major product when a sterically unhindered base is used (recall the regioselectivity of the E2 reaction).

The compound has two β positions, and there are two protons on the left and one proton on the right side. Apparently, the β hydrogen on the right cannot participate in an E2 reaction, as seen from the product of the reaction:

So, why is this cyclohexane selective in involving only certain β-hydrogens in elimination reactions?

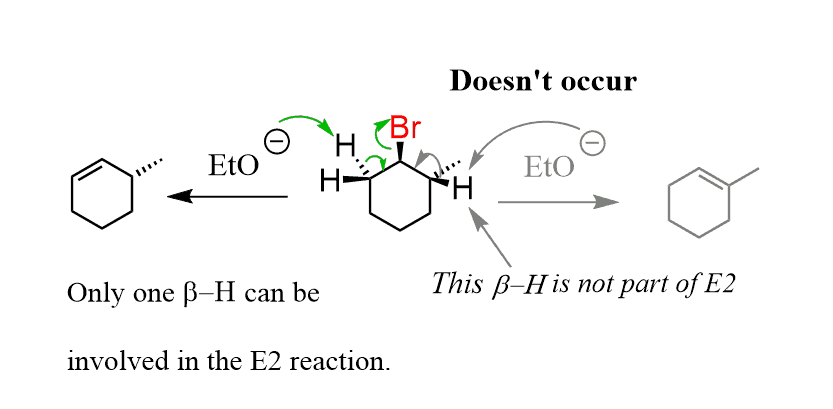

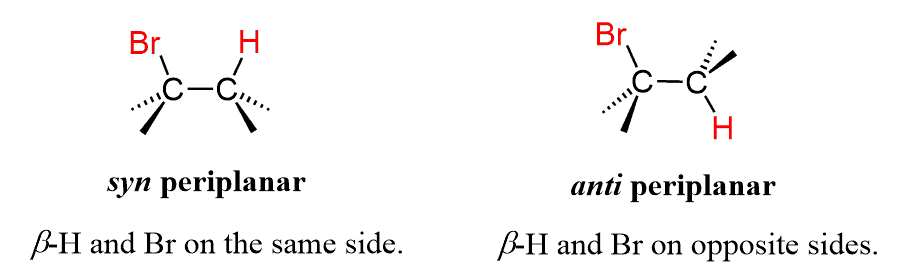

To answer this question, recall first the requirement for an anti-periplanar conformation of the leaving group and the β hydrogen in E2 reactions:

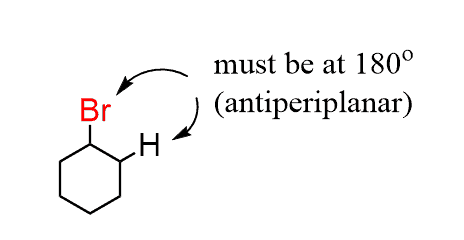

Cyclohexanes are not different, and the anti-periplanar geometry is still needed for them to undergo E2 elimination:

To better demonstrate this alignment of the Br and the β hydrogens, we need to draw the two chair conformations of the cyclohexane:

Notice that the anti-periplanar (180o) alignment of the Br and the β hydrogen is only possible when the Br occupies an axial position. None of the β hydrogens appear to be at 180o to the Br when it is equatorial.

Therefore, the elimination is only possible when the leaving group is in an axial position. And this explains the regiochemistry of the E2 reaction for the cyclohexane we are discussing:

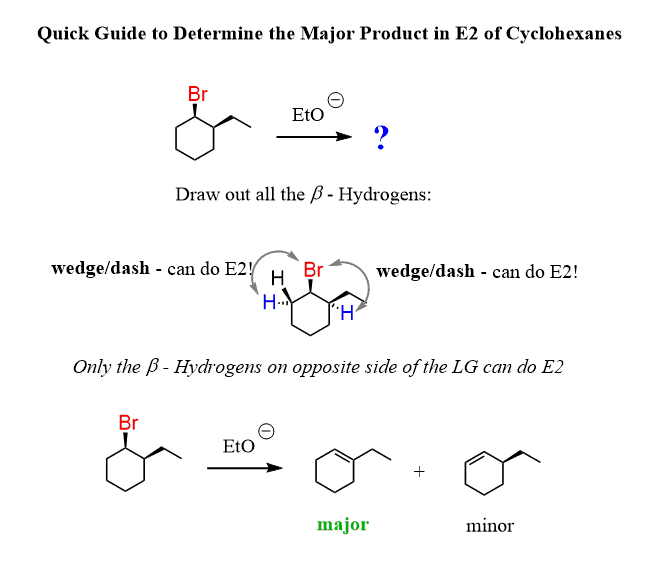

The alignment of the β hydrogen and the leaving group is best shown on the chair conformations, which do take time to draw.

Fortunately, however, you do not need to draw the chair conformations every time when working on an elimination reaction of a substituted cyclohexane.

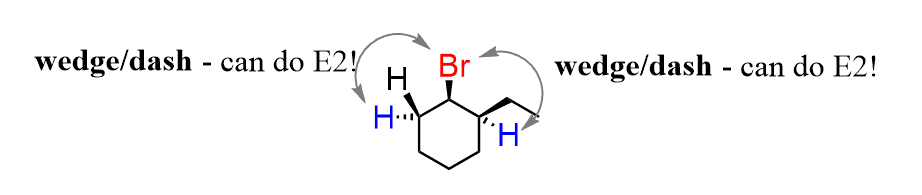

The shortcut here is to remember that the leaving group and the β hydrogen must be on opposite sides of the ring (one on a wedge and the other on a dash or Vice Versa).

For example, the following cyclohexane has two β-hydrogens, and they are both on the opposite sides of the leaving group:

The leaving group is a wedge, and there are dash β-hydrogens on both sides. This means the regioselectivity of the elimination can be determined based on whether an unhindered or a bulky base is used.

Indeed, when treated with a strong sterically unhindered base such as sodium ethoxide, it does form the Zaitsev product as expected from the regioselectivity of the E2 reaction:

On the other hand, if a bulky base such as potassium tert-butoxide is used, the Hoffman product predominates since the sterically hindered base now attacks the more accessible proton, producing the less stable alkene:

To summarize, remember, in the E2 reaction of cyclohexanes, only the hydrogen opposite to the leaving group (wedge/dash or dash/wedge) can participate in the elimination.

The Rate of the E2 Reaction of Cyclohexanes

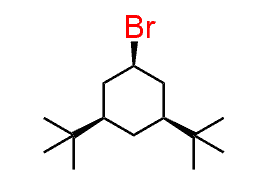

How fast a given cyclohexane undergoes E2 elimination depends on how stable the chair conformation with the leaving group in the axial position is.

For example, let’s compare these two compounds:

Suppose we are asked to determine which compound is expected to react faster in E2 elimination.

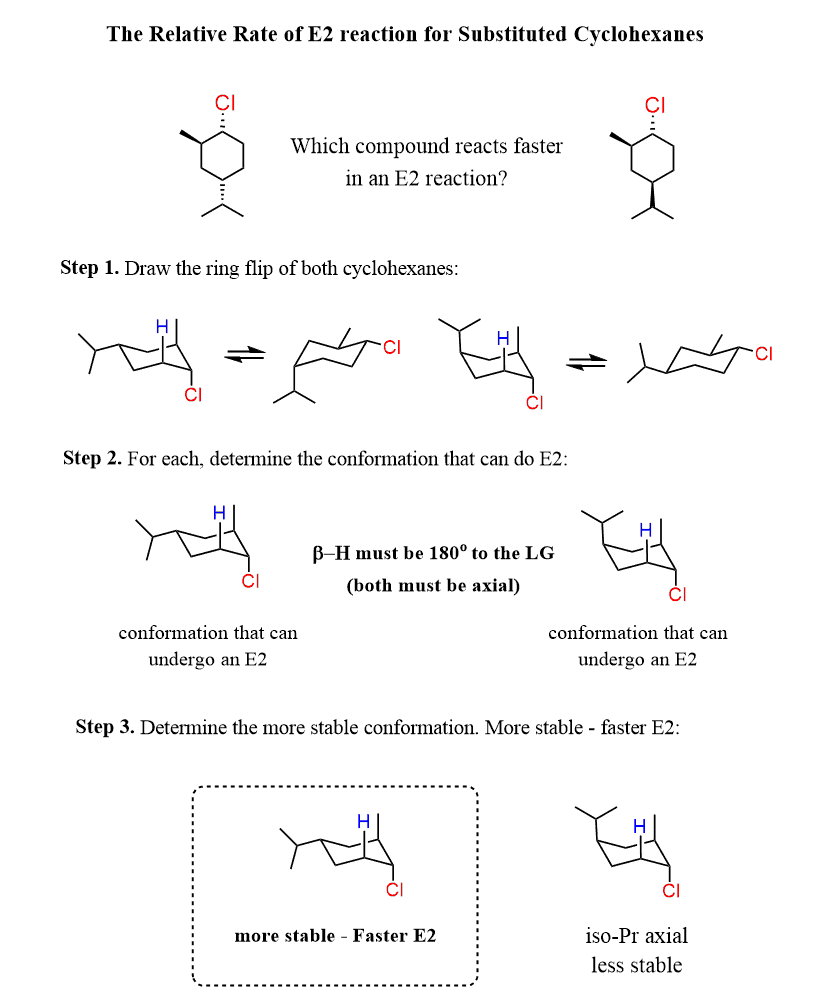

Granted, the base and leaving group are the same, the rate of the reaction will depend on the stability of the chair conformation with a trans diaxial arrangement of the leaving group and the corresponding β-hydrogen.

Let’s summarize this by drawing the ring flip of these cyclohexanes:

When comparing the two chair conformations capable of undergoing E2 elimination, we can see that the first compound puts the large isopropyl group in the equatorial position, while the second one has it in the axial.

This means the first compound will react faster as the conformation with an equatorial isopropyl group is more stable than the one with an axial isopropyl group.

The E1 Elimination of Cyclohexanes

These observations about the elimination reactions of cycloalkanes are not entirely relevant to E1 reactions.

For example, the following cyclohexane will produce the Zaitsev product when treated with a weak base:

This is explained by the difference in the mechanisms of E2 and E1 reactions. Remember, E1 reactions are stepwise, and the first step is the loss of the leaving group, forming a carbocation intermediate.

In the reaction above, the resulting carbocation undergoes a rearrangement, and as a result, the more substituted alkene is formed as the major product:

The rearrangement, however, is not the only reason that the Zaitsev product predominates when a substituted cyclohexane undergoes an E1 elimination.

Let’s consider the following cyclohexane, with an extra methyl group that prevents the rearrangement of the carbocation since it is now a tertiary carbocation:

The difference with the E2 mechanism is that here there is no leaving group, and the β-hydrogen must be aligned with the empty p orbital of the carbocation in order to participate in elimination. This alignment is possible when β-hydrogen is axial. If two β-hydrogens are axial, then the one resulting in the Zaitsev product is removed.

Check out this 65-question, Multiple-Choice Quiz with a 3-hour Video Solution covering Nucleophilic Substitution and Elimination Reactions:

Nucleophilic Substitution and Elimination Practice Quiz