The addition-elimination mechanism represents certain types of substitutions where the replacement of the leaving group is achieved in two consecutive steps – addition, and elimination. The most common example is the acyl substitution where one group connected to the carbonyl is replaced with another. For example, acid chlorides can be converted to ester by a nucleophilic acyl substitution of acid chlorides:

The mechanism of acyl substitution is often shown as a single, SN2 type, a step which is incorrect because the orbital alignment of the leaving group does not allow it.

Instead, in the first step, we have a nucleophilic addition to the C=O bond which results in an ionic tetrahedral intermediate. The C=O bond is then restored by expelling the group that best stabilizes the negative charge. In other words, the best leaving group is expelled from the tetrahedral intermediate forming a new carbonyl compound:

The nucleophilic acyl substitution is very common in the reactions of carboxylic acids and their derivatives, and you are going to see it a lot. Below are some examples of nucleophilic acyl substitution via the addition elimination mechanism.

The Reaction of Esters with Grignard Reagents

Reactions of Esters with Amines

Reaction of Carboxylic Acids with Organolithiums

Addition-Elimination Mechanism in Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution

Another example of an addition-elimination mechanism if the nucleophilic aromatic substitution. There are two main mechanisms: addition-elimination or elimination-addition, also known as the benzyne mechanism which is sometimes considered as a separate reaction.

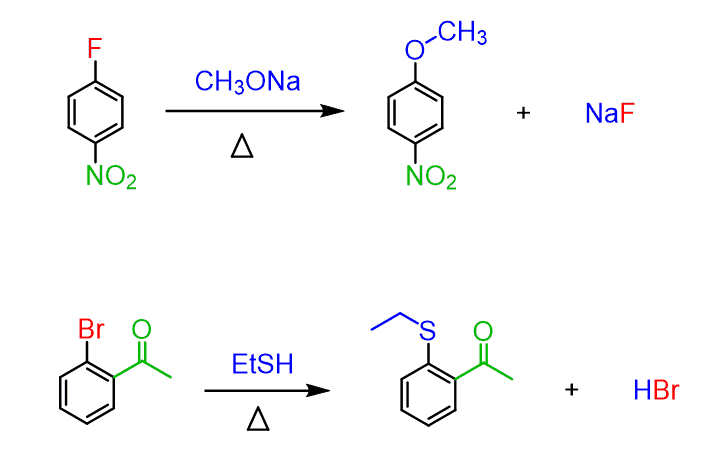

Nucleophilic aromatic substitutions that go via the addition-elimination mechanism are the ones in the left column. Notice that the nitro group is typically used as an electron-withdrawing group even though other groups such as carbonyls can also activate the ring toward a nucleophilic attack.

As for the nucleophile, a variety of charged and neutral strong nucleophiles such as –OH, –OR, –SR, NH3, and other amines can be used.

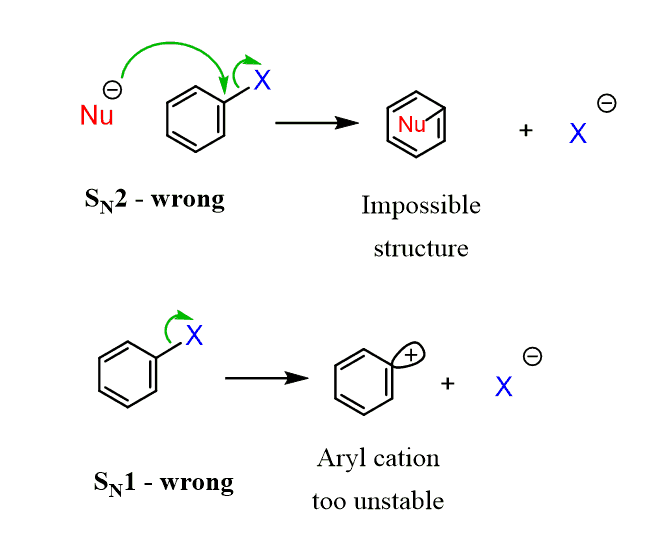

Like in other substitution reactions, the leaving group halide is replaced by a nucleophile. The mechanism of nucleophilic aromatic substitution, however, is different than what we learned in the SN1 and SN2 reactions. The key difference is that aryl halides cannot undergo an SN2 by a backside attack of the nucleophile and, unlike SN1, the loss of the leaving group cannot occur since the phenyl cations are very unstable:

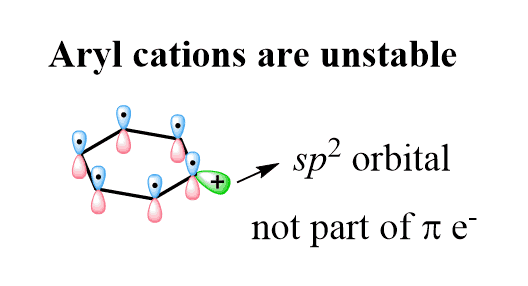

Even though the cation is surrounded by double bonds, it cannot be stabilized because the p orbital, being part of the aromatic ring, is full and the empty orbital is an sp2 orbital perpendicular to the conjugated p orbitals:

So, no SN1 or SN2 in nucleophilic aromatic substitutions!

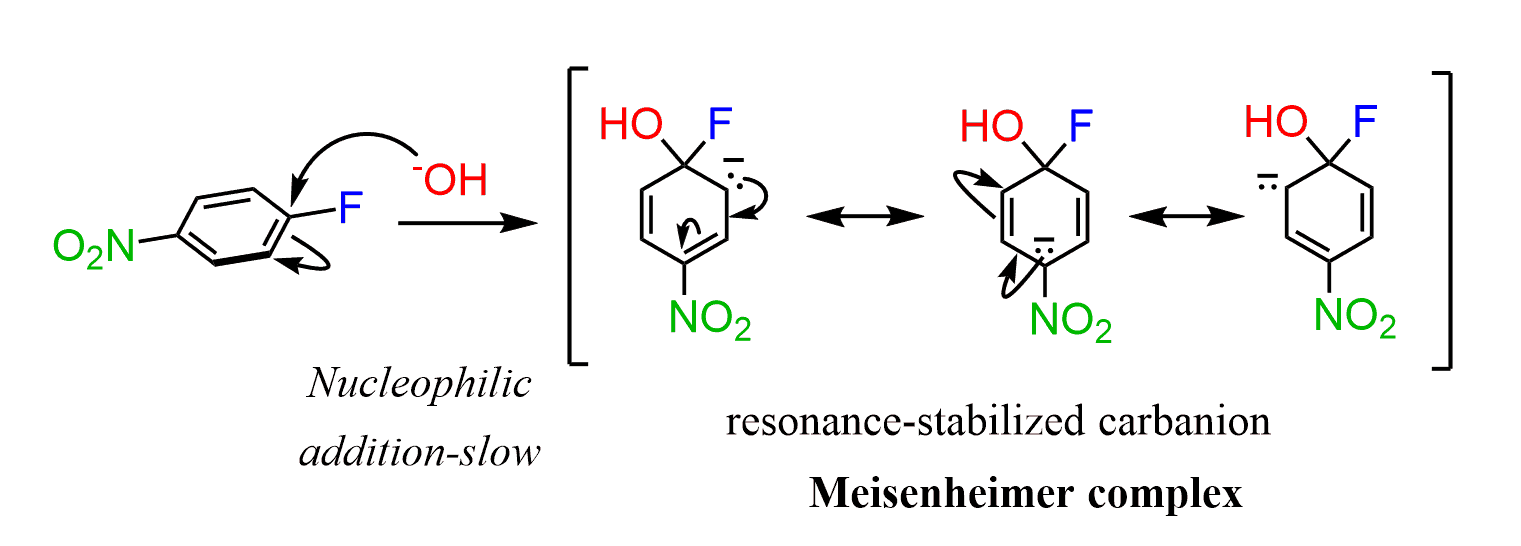

Instead, the reaction occurs either by an addition-elimination mechanism. It starts with the addition of the nucleophile to the aromatic ring generating a resonance-stabilized carbanion.

This addition occurs from either face, almost perpendicular, of the aromatic ring because that’s where the LUMO orbitals are. The resonance-stabilized carbanion is called a Meisenheimer complex:

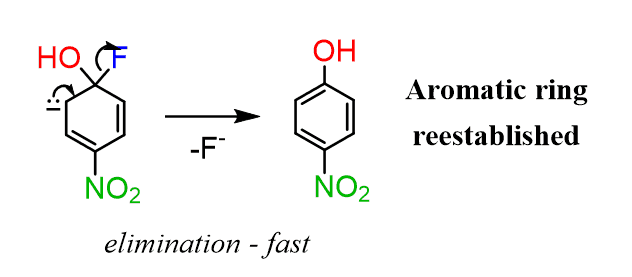

In the next step, the leaving group is eliminated, restoring the aromaticity of the ring:

You may wonder why the ring did not kick out the nucleophile instead of the halide. And this simply has to do with their stability – a better leaving group is better stabilized. That is why the nucleophile must be a stronger base than the leaving group to favor the desired replacement.

You can find more about the mechanism and regiochemistry of nucleophilic aromatic substitution in a separate article here.

Check Also:

- LiAlH4 and NaBH4 Carbonyl Reduction Mechanism

- Fischer Esterification

- Ester Hydrolysis by Acid and Base-Catalyzed Hydrolysis

- What is Transesterification?

- Esters Reaction with Amines – The Aminolysis Mechanism

- Ester Reactions Summary and Practice Problems

- Preparation of Acyl (Acid) Chlorides (ROCl)

- Reactions of Acid Chlorides (ROCl) with Nucleophiles

- Reaction of Acyl Chlorides with Grignard and Gilman (Organocuprate) Reagents

- Reduction of Acyl Chlorides by LiAlH4, NaBH4, and LiAl(OtBu)3H

- Preparation and Reaction Mechanism of Carboxylic Anhydrides

- Amides – Structure and Reactivity

- Naming Amides

- Amides Hydrolysis: Acid and Base-Catalyzed Mechanism

- Amide Dehydration Mechanism by SOCl2, POCl3, and P2O5

- Amide Reduction Mechanism by LiAlH4

- Amides Preparation and Reactions Summary

- Amides from Carboxylic Acids-DCC and EDC Coupling

- The Mechanism of Nitrile Hydrolysis To Carboxylic Acid

- Nitrile Reduction Mechanism with LiAlH4 and DIBAL to Amine or Aldehyde

- The Mechanism of Grignard and Organolithium Reactions with Nitriles

- Carboxylic Acids to Ketones

- Carboxylic Acids and Their Derivatives Practice Problems

- Carboxylic Acids and Their Derivatives Quiz