Alkyl halides can be converted to alcohols by reacting them with water or hydroxide ion. Recall that the hydroxide ion is a good nucleophile, and water is a poor nucleophile; therefore, the conversions occur via SN2 and SN1 mechanisms, respectively.

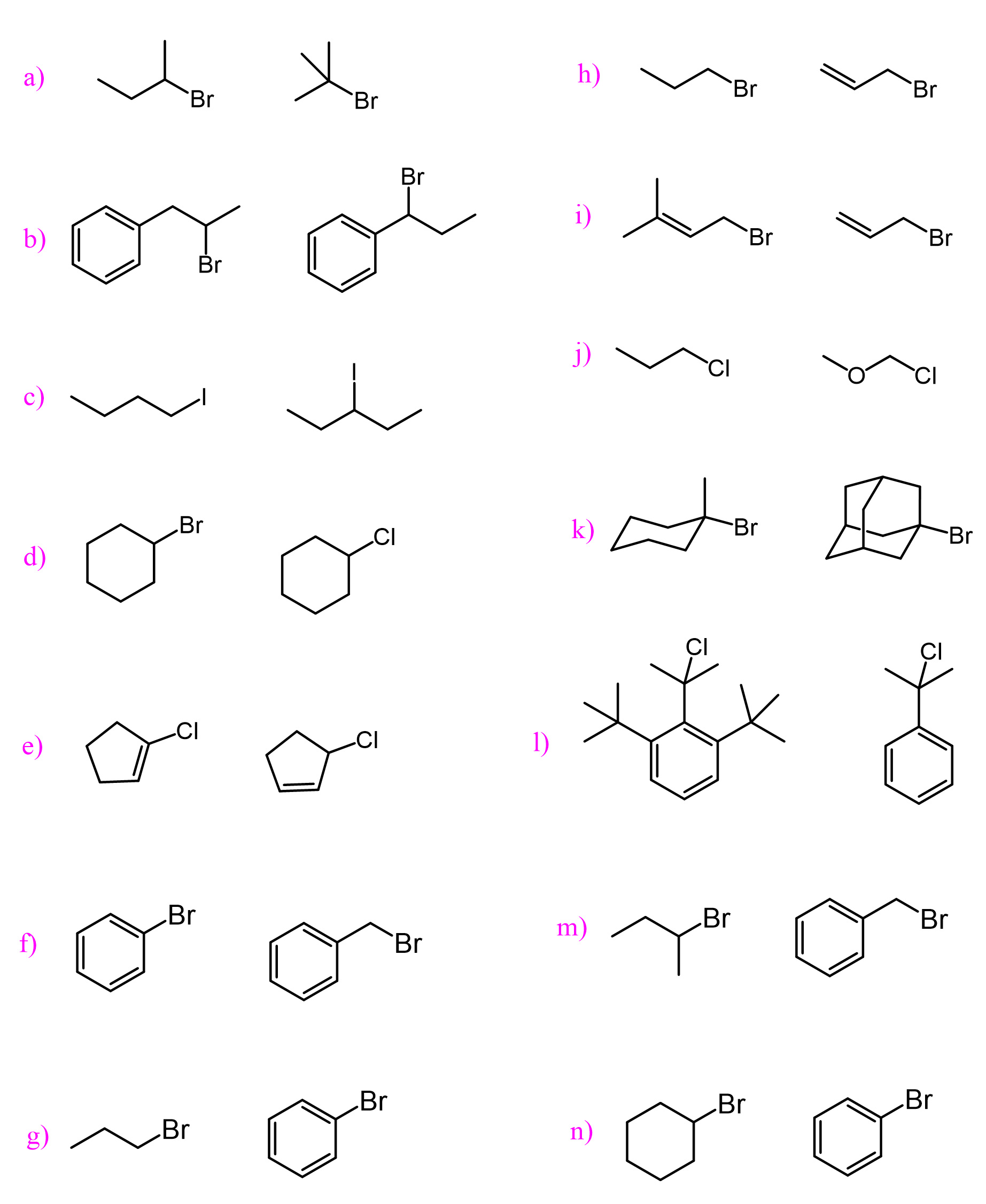

There are a few key parameters to consider when choosing the method for converting an alkyl halide to alcohol. Depending on where your class stands, you may want to read this article about deciding between SN1, SN2, E1, and E2 reactions. To get there, you’d need to have each of these mechanisms converted.

Today’s discussion is specifically about converting alkyl halides to alcohols via SN1 and SN2 reactions. Nonetheless, let’s briefly mention the basic correlation between the structure of the alkyl halide and the preferred substitution and elimination pathways:

Primary – SN2, tertiary – SN1.

NaOH is a good nucleophile and a strong base, so E2 elimination will be the main reaction of secondary alkyl halides.

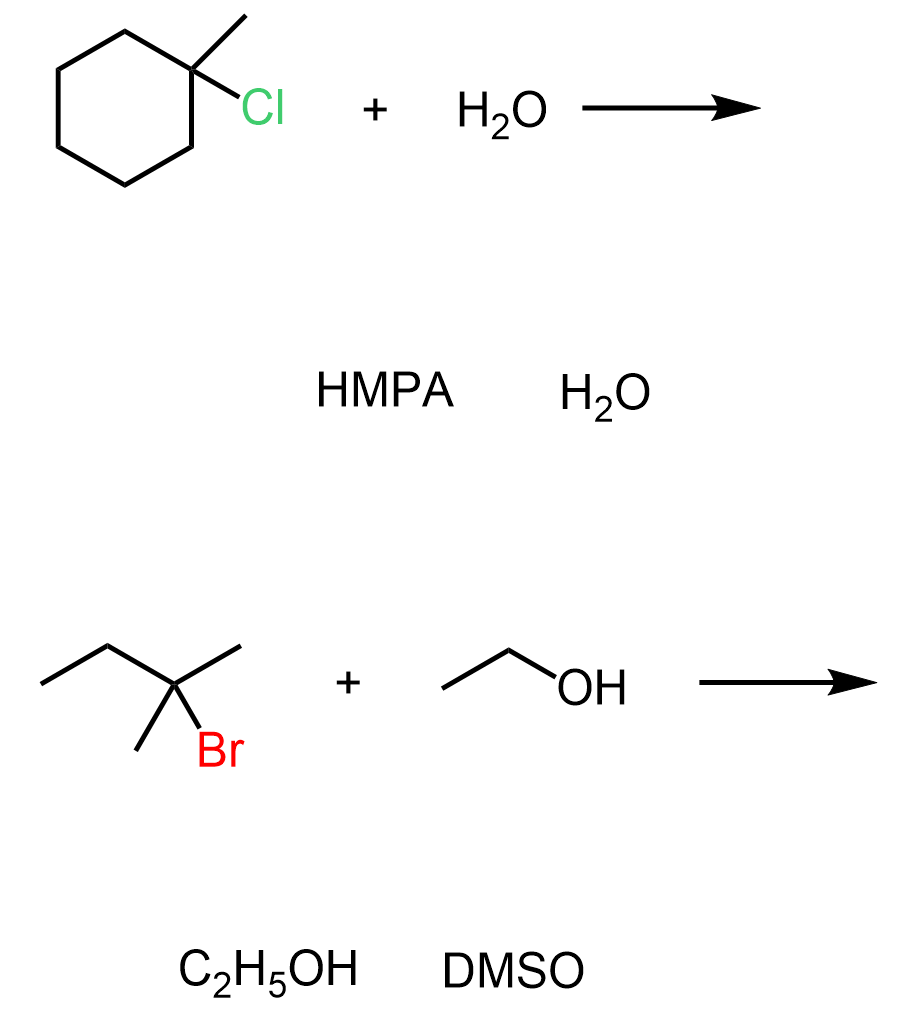

Therefore, for a primary alkyl halide, we’ll use a hydroxide base such as NaOH, while for tertiary alkyl halides, we need a weak nucleophile like water to prevent the undesired elimination path. We can use water to convert secondary alkyl halides to alcohols too. One concern here is the possibility of a rearrangement because the reaction goes via a secondary carbocation that may convert into a more stable tertiary carbocation.

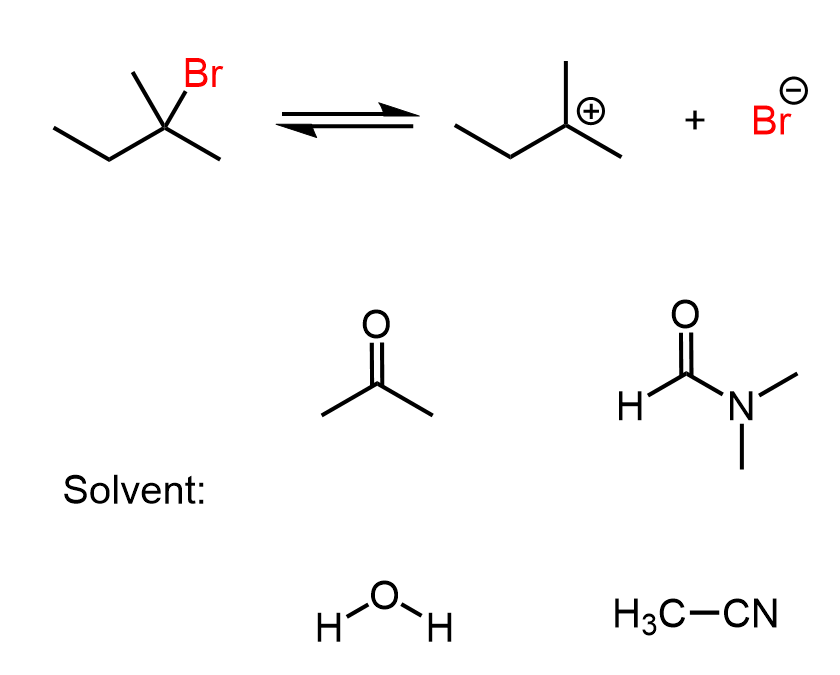

These SN1 reactions, and in any reactions where the solvent itself acts as the nucleophile, are also known as solvolysis.

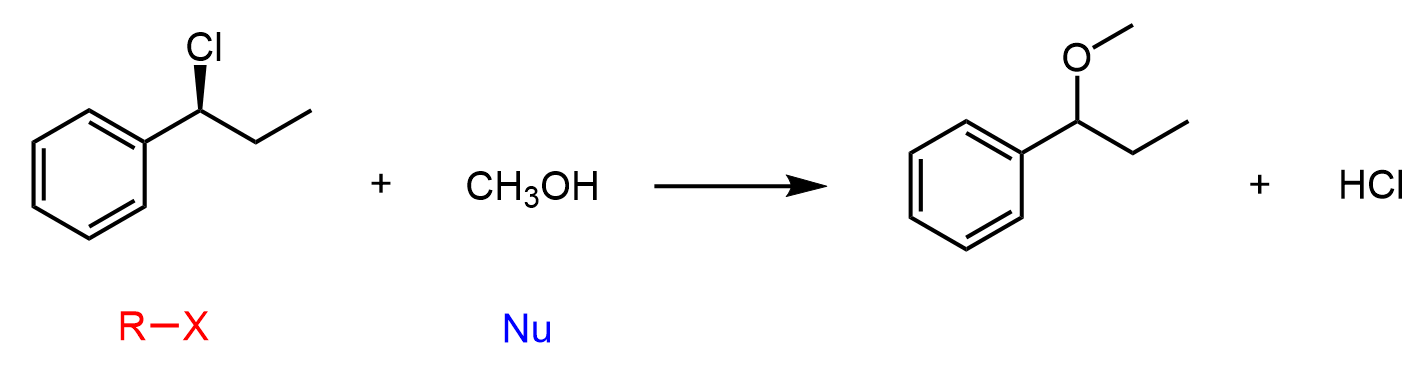

Another common weak nucleophile is an alcohol, and when alkyl halides undergo solvolysis in an alcoholic solvent, the product is typically an ether. This makes solvolysis a useful strategy for forming both alcohols and ethers, depending on the solvent used.

Primary Alkyl Halides to Alcohols

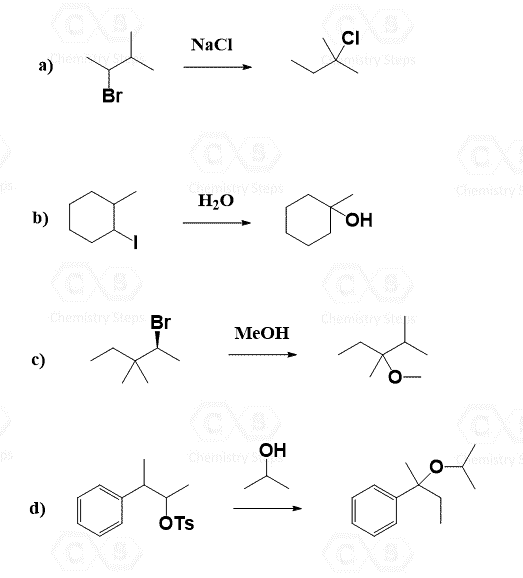

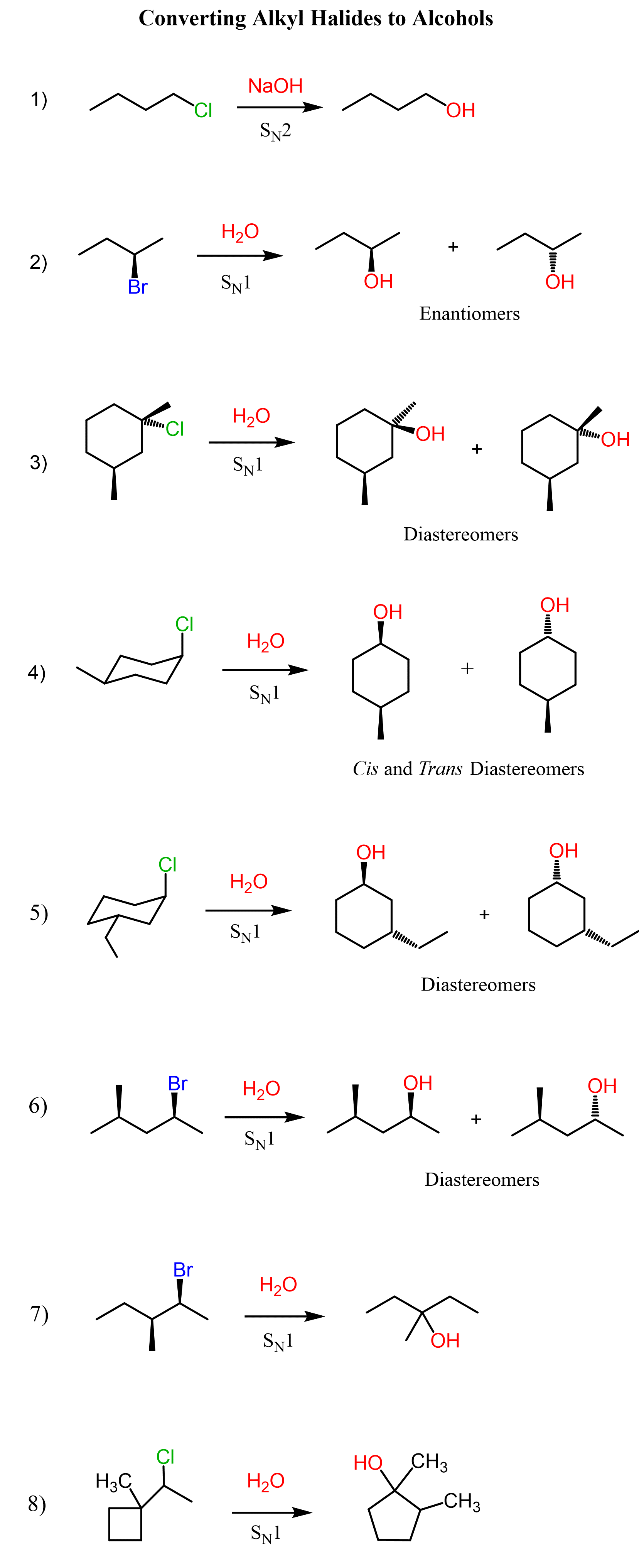

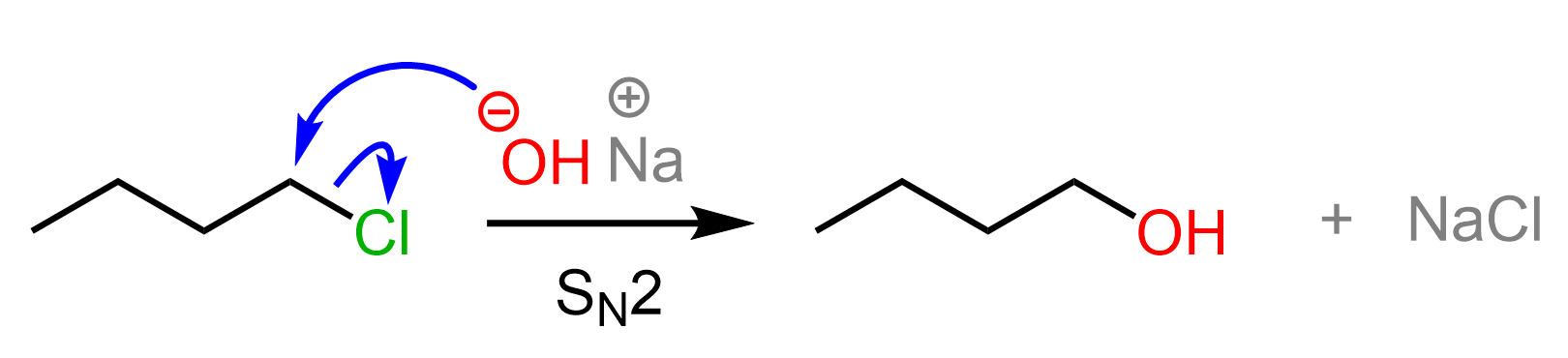

Primary alkyl halides are converted into alcohols by reacting them with a strong hydroxide such as NaOH, KOH, or LIOH. The reaction goes by an SN2 mechanism as the alkyl halide is not hindered, and we have a good nucleophile:

Secondary Alkyl Halides to Alcohols

Let’s first mention that using a hydroxide for converting a secondary alkyl halide to an alcohol is not the best option because they are also strong bases, and therefore, the E2 elimination predominates.

Therefore, the reaction with water (hydrolysis) is preferred. The reaction, in this case, goes via an SN1 mechanism because water is a poor nucleophile:

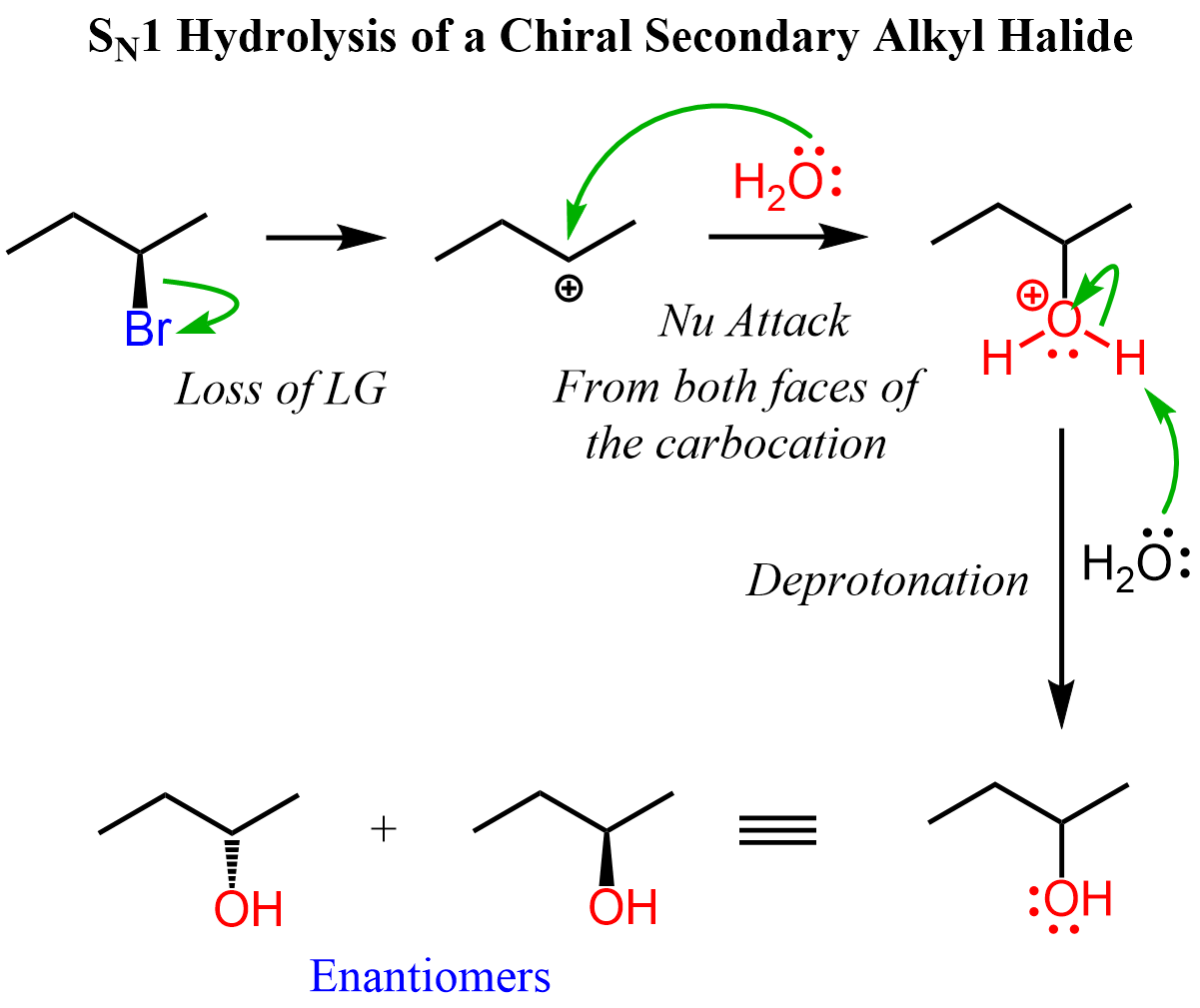

Recall that the SN1 reaction is a stepwise mechanism, and it goes via a carbocation intermediate. The formation of carbocations indicates a couple of possibilities, we need to consider: 1) If a chiral alkyl halide is used, it is racemized into the corresponding alcohols, 2) Whenever possible, a rearrangement will occur.

Let’s see how a chiral alkyl halide gives a racemic mixture of enantiomers on the example of (R)-2-bromobutane with water:

The reason for forming two enantiomers is the planar geometry of the sp2-hybridized carbocation. The nucleophilic attack occurs at both sides of the carbocation, producing the R and S configurations in equal amounts.

Tertiary Alkyl Halides to Alcohols

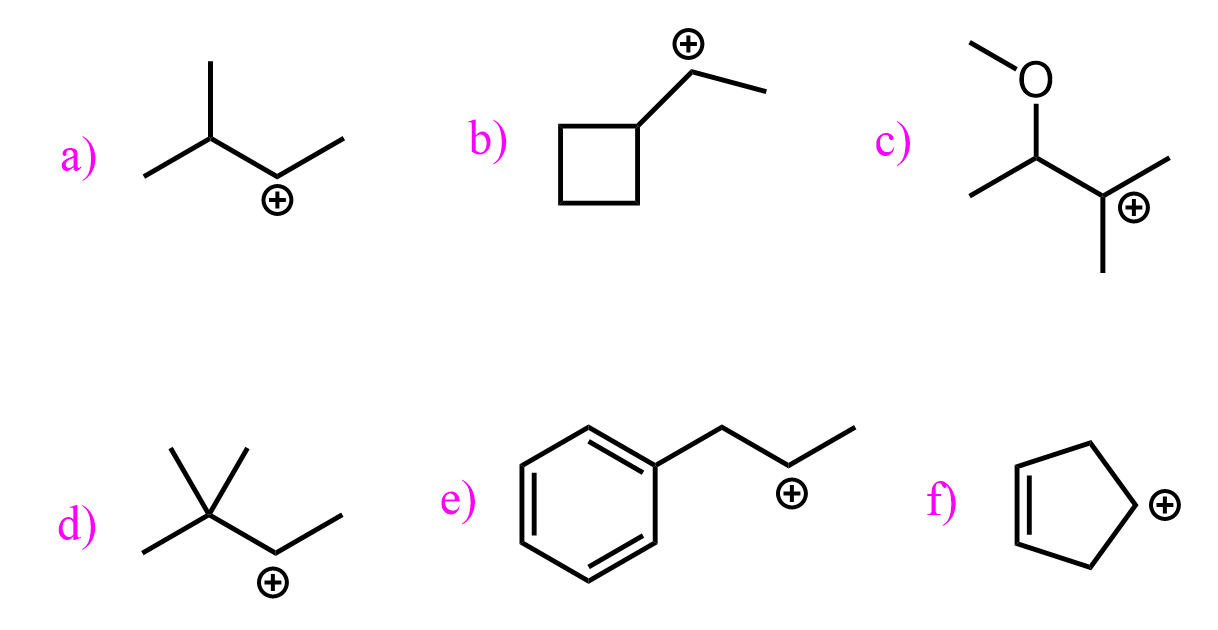

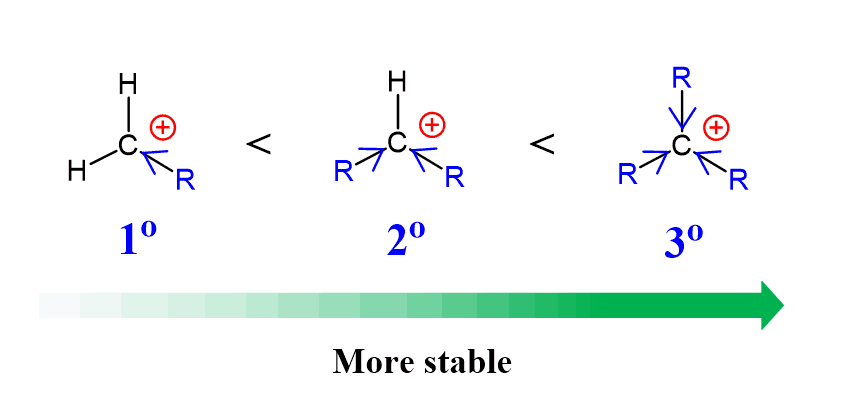

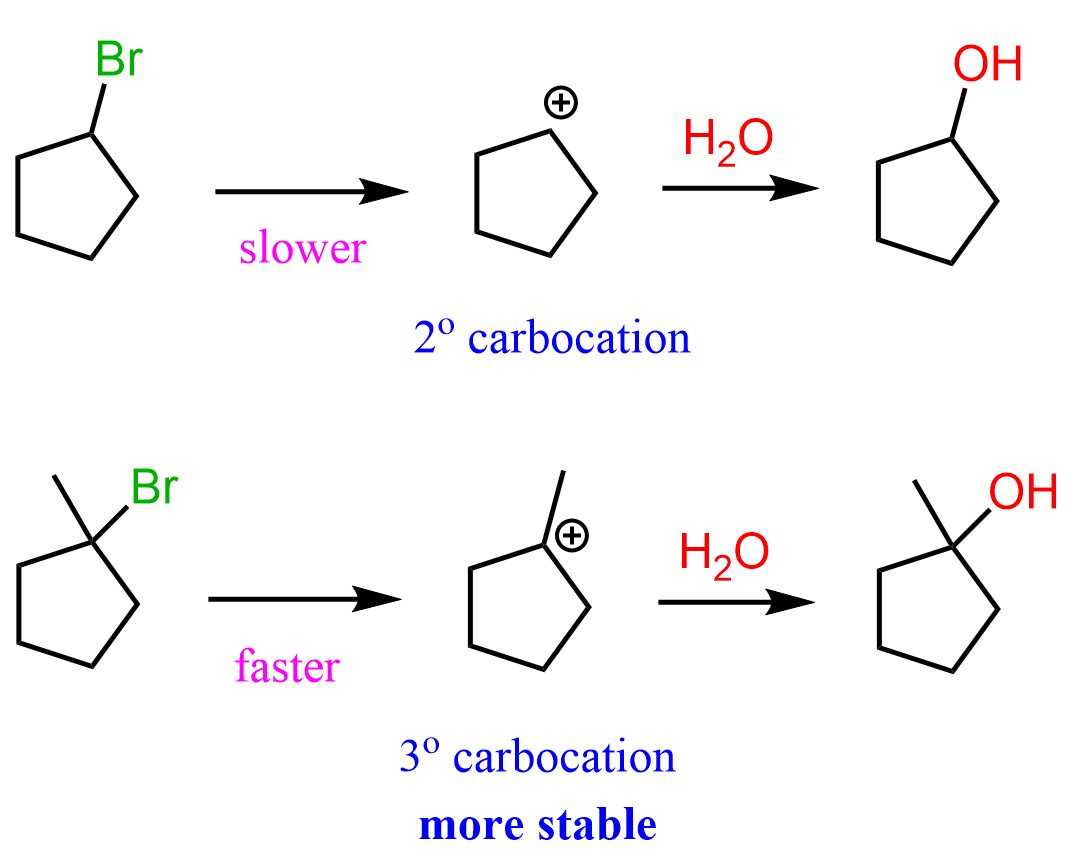

Tertiary halides are the best choice for converting alkyl halides to alcohols when water is used as the nucleophile. The reason for this is the great (relatively – they are still unstable intermediates) stability of tertiary carbocations. Recall that carbocations get more stable with the number of alkyl groups as they stabilize the positive charge on the carbon atom:

Breaking the C-halogen bond is the rate-determining step of the SN1 mechanism, and having a stable carbocation makes the process less unfavorable.

The Stereochemistry of Alkyl Halide Hydrolysis

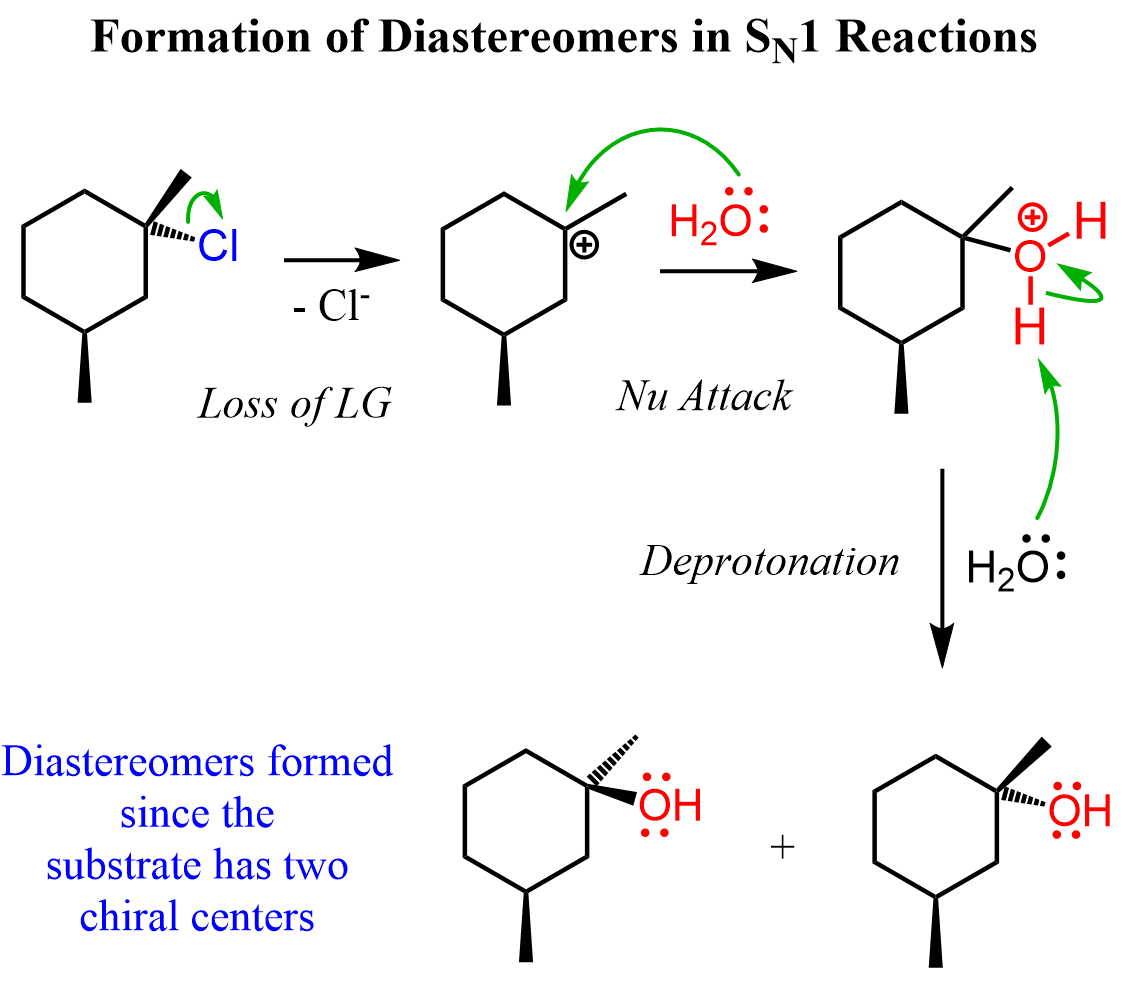

We have seen that in SN1 reactions, an alkyl halide with a chiral reactive center gives a racemic mixture of enantiomers. This is the most common pattern you will see in your class and will be tested on the tests. However, you need to know that the formation of diastereomers is also possible if the alkyl halide contains two chirality centers and only one is part of the reaction. For example, aside from the carbon bearing the leaving group, there is another chiral center in the following alkyl halide. The racemization of the reaction center leads to two diastereomers because the other chiral center is not part of the reaction and keeps its configuration:

So, one may think, why not use a hydroxide to prevent the formation of carbocation and subsequent racemization, i.e., push the reaction to an SN2 substitution.

We need to always remember the competition between elimination and substitution reactions. In this case, we cannot use a hydroxide because the E2 elimination will be the only outcome when reacting a strong base with a tertiary alkyl halide:

Once again, check out this post about choosing between SN1, SN2, E1, and E2 reactions.

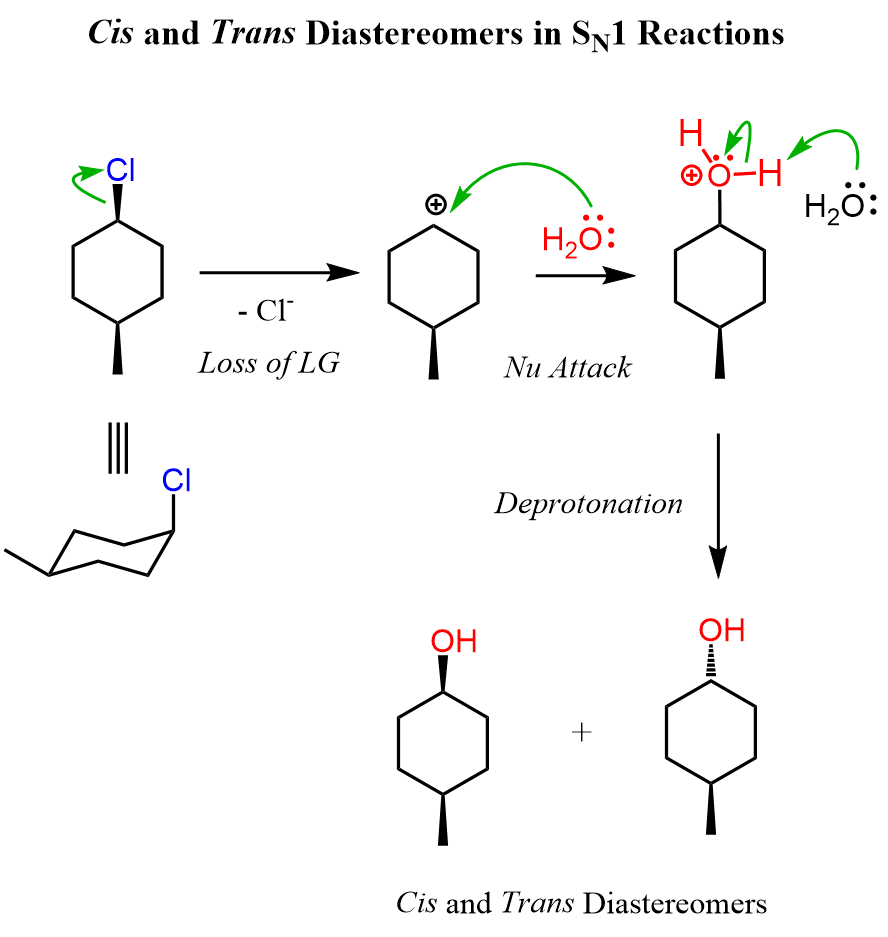

Achiral alkyl halides can also produce a pair of diastereomers in SN1 reactions. For example, compare the following hydrolysis reactions. Both are secondary alkyl halides; however, the difference here is that the first molecule is achiral as it has a plane of symmetry. The two alcohols of the achiral alkyl halide are diastereomers because, remember, diastereomers are stereoisomers that are not mirror images.

We can look at these alcohols as cis and trans isomers because of the relative orientation of the methyl and OH groups. So, keep in mind that cis and trans isomers are diastereomers even if there are no chiral centers in the given molecules.

Let’s also draw the SN1 mechanism of this hydrolysis reaction:

Try to draw the mechanism of reactions 4 and 5 before looking at this one first. Refer to this article for converting cyclohexanes into chair conformations and vice versa.

Rearrangements in the Reactions of Alkyl Halides with Water

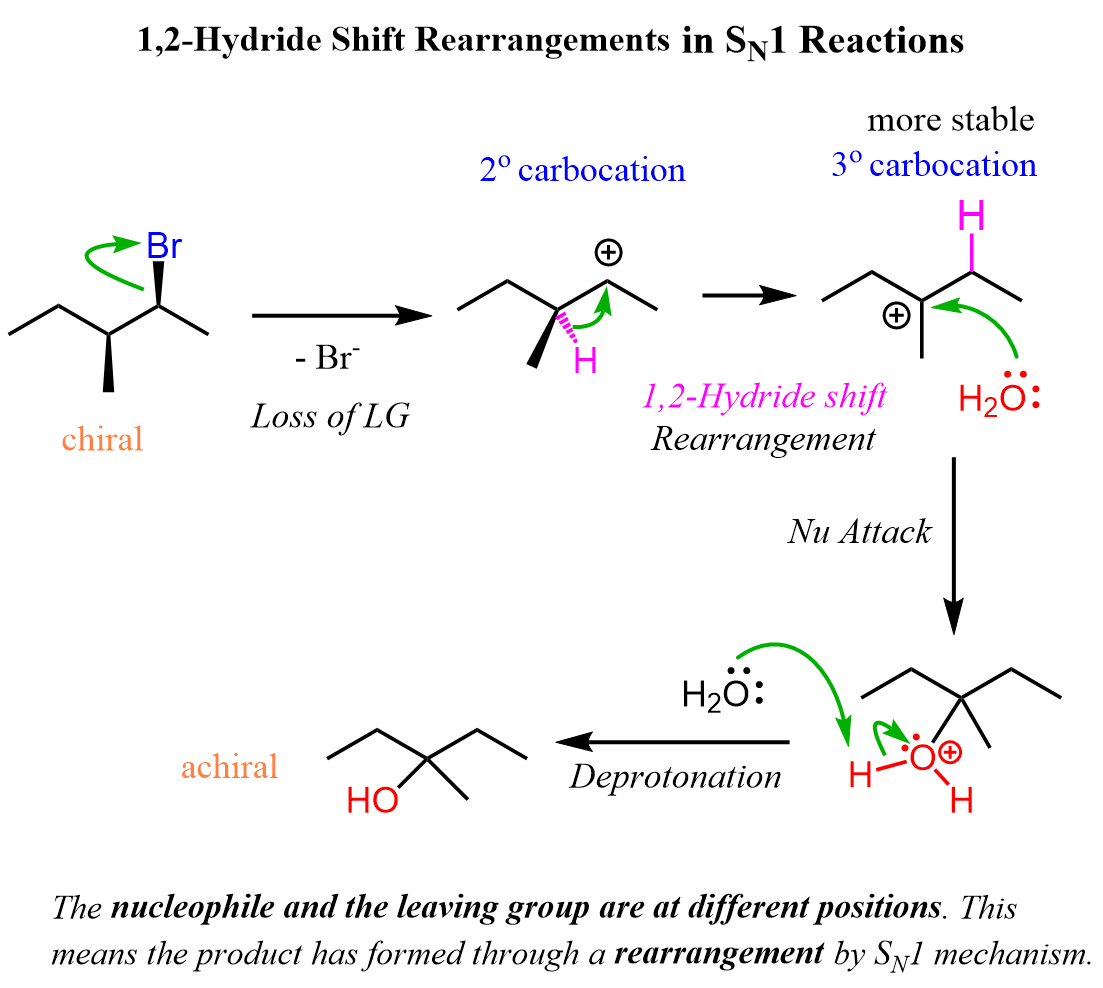

We have talked about the stereochemistry of SN1 reactions and saw that enantiomers and diastereomers can be formed from chiral alkyl halides. Let’s now address the second important consideration about carbocations, which is the rearrangements. Always keep in mind the possibility of a rearrangement when the reaction goes via a carbocation intermediate. We mentioned that the stability of carbocations increases with the degree of substitution, so let’s see how a chiral alkyl halide gives a rearrangement product as a result of the secondary carbocation rearranging into a tertiary carbocation:

Notice that the chirality of the middle carbon is lost upon the hydride shift because carbocations are sp2-hybridized and only have three atoms connected to the positively charged carbon. Because of symmetrical structures, the nucleophilic attack of water produces an achiral alcohol.

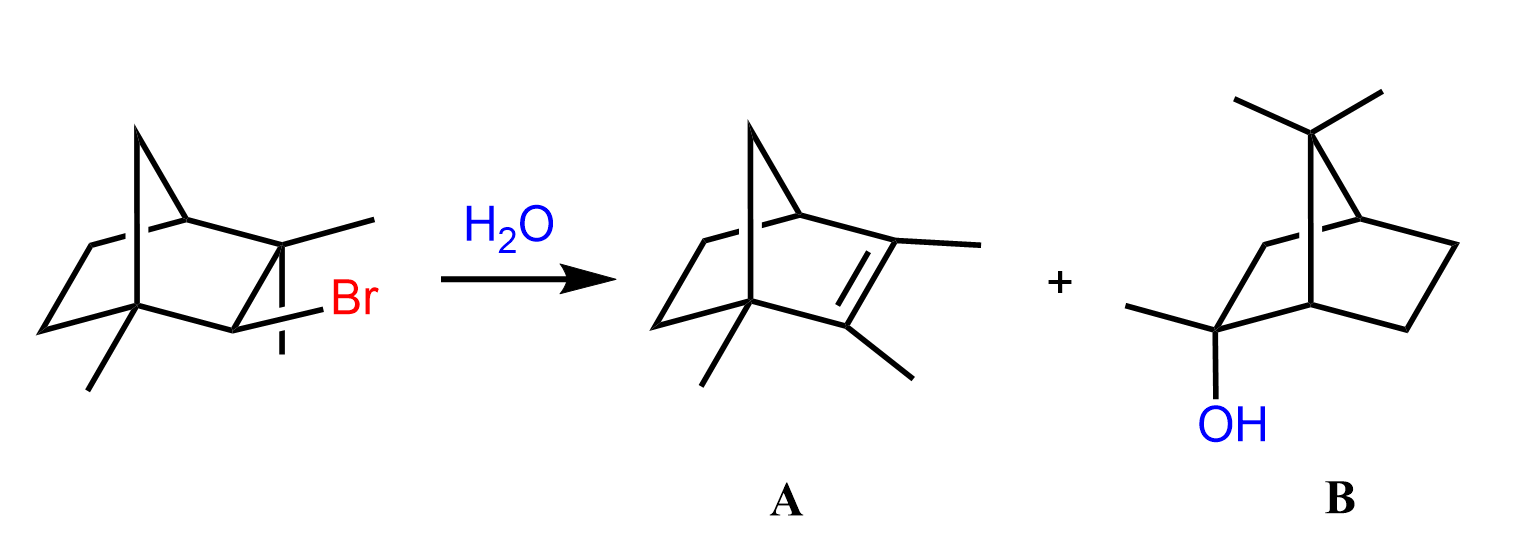

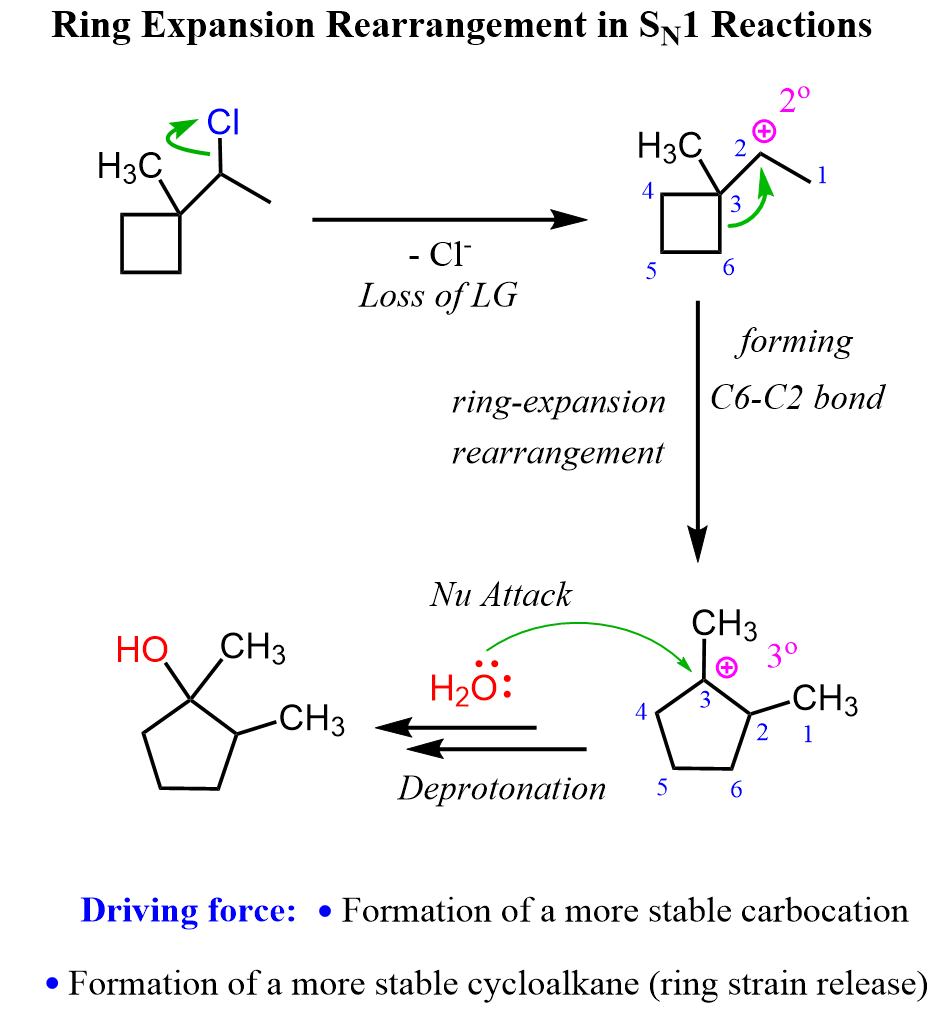

Ring Expansion Rearrangements in SN1 Reactions

A common type of carbocation rearrangement is the ring expansion of 4 or 5-membered cycloalkanes. The driving force in these reactions is both the increased stability of carbocations (2o-3o) and the ring itself. Remember, a 4-membered ring has quite a high ring strain, which is released when expanded to a 5-membered ring. Reaction 8 is an example of ring-expansion rearrangement in an SN1 reaction:

For cyclopentanes, even though they are very stable molecules, they are still associated with little ring strain. This, combined with the possibility of rearrangement from secondary to tertiary carbocation, facilitates the ring expansion rearrangement of 5-membered rings to cyclohexenes.

Summary of Converting Alkyl Halides to Alcohols

Alkyl halides can be converted to alcohols by reacting them with either hydroxides or water. Hydroxides are good nucleophiles and strong bases; therefore, they are best suited for the conversion of primary alkyl halides.

Never use a tertiary alkyl halide with a hydroxide to prepare an alcohol because E2 reaction will predominate, giving the corresponding alkene as the major product. Tertiary alkyl halides are the best candidates for SN1 conversion to alcohols using water as the poor nucleophile.

Secondary alkyl halides can do both SN1 and SN2, however, using a strong base such as the hydroxide ion favors E2 elimination. Therefore, water is used for converting secondary alkyl halides to alcohols via SN1 mechanism.

SN1 reactions proceed via racemization of the chiral center that is part of the reaction. If a new chirality center is formed during the addition of the nucleophile, a pair of enantiomers is obtained. A common exception is when the substrate already contains an additional chiral center that is not part of the reaction. In this case, a pair of diastereomers is formed. Check this article on the most common exceptions in SN1 and SN2 reactions.

Rearrangements will occur whenever possible, so always be aware of them when dealing with unimolecular reactions such as SN1 and E1.

Organic Chemistry Reaction Maps

Never struggle again to figure out how to convert an alkyl halide to an alcohol, an alkene to an alkyne, a nitrile to a ketone, a ketone to an aldehyde, and more! The comprehensive powerfull Reaction Maps of organic functional group transformations are here!