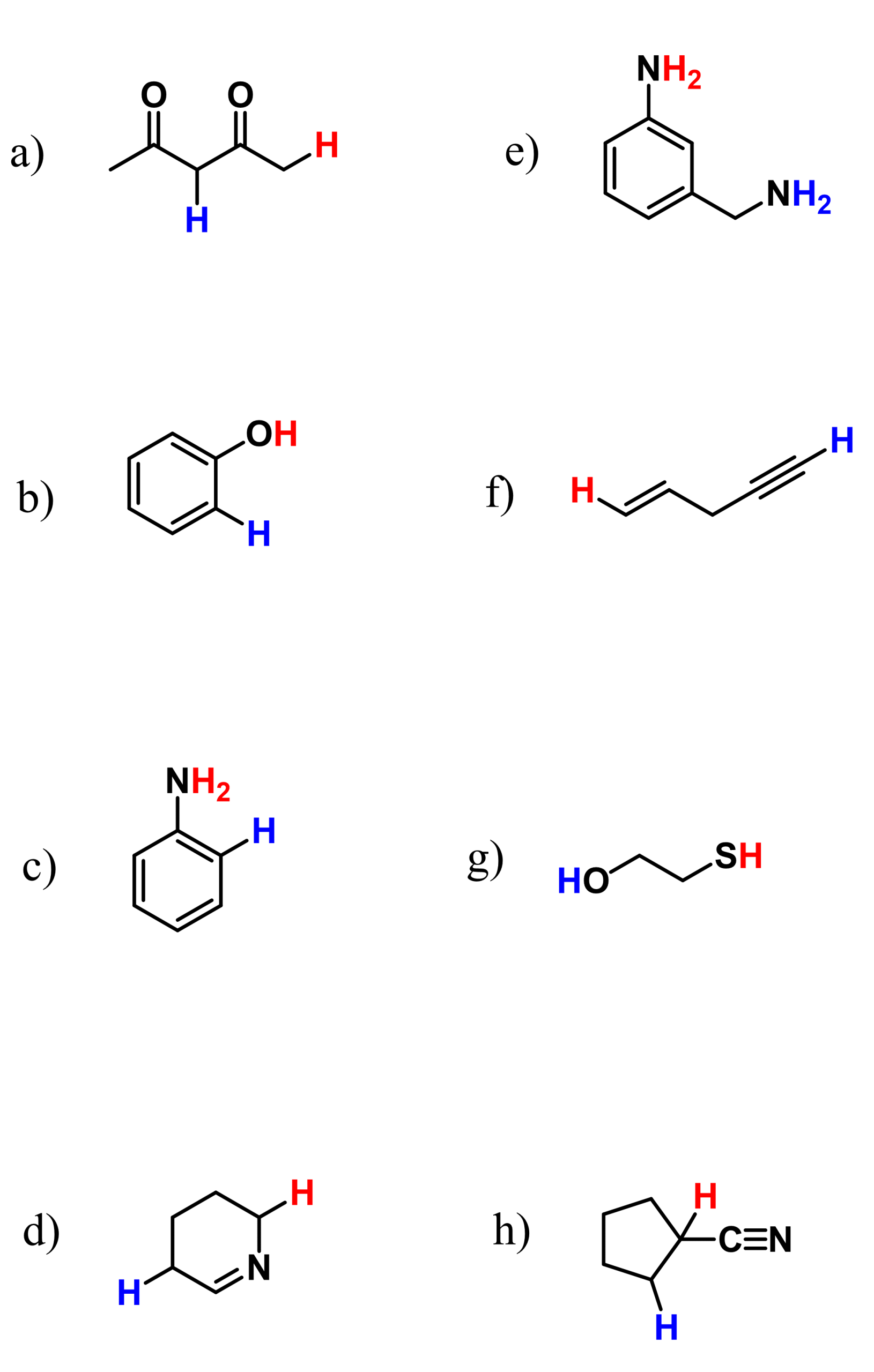

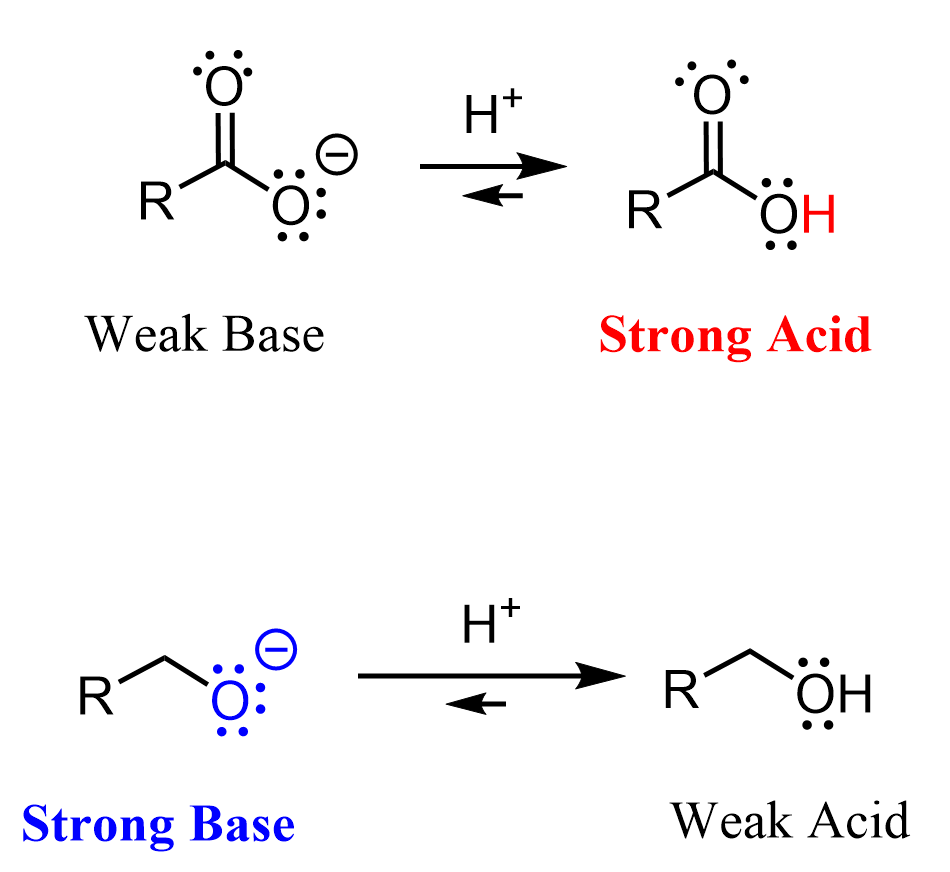

Let’s first describe what a strong base and a strong acid is in the simplest words:

A strong acid, if we are talking about a protic acid and not a Lewis acid in general, is one that has no problem losing an H⁺, which means it can successfully stabilize the negative charge of its conjugate base.

A strong base, on the other hand, is one that “can’t handle” its negative charge and is looking for an electron‑deficient species such as a proton or another Lewis acid.

As an example of a strong base, consider the ethoxide ion (the conjugate base of ethanol), and let’s take acetic acid as an example of a strong acid.

Remember, strong and weak is relative, and we know that acetic acid is much weaker than most inorganic acids, but that is not the point of today’s discussion.

Acidity and Resonance

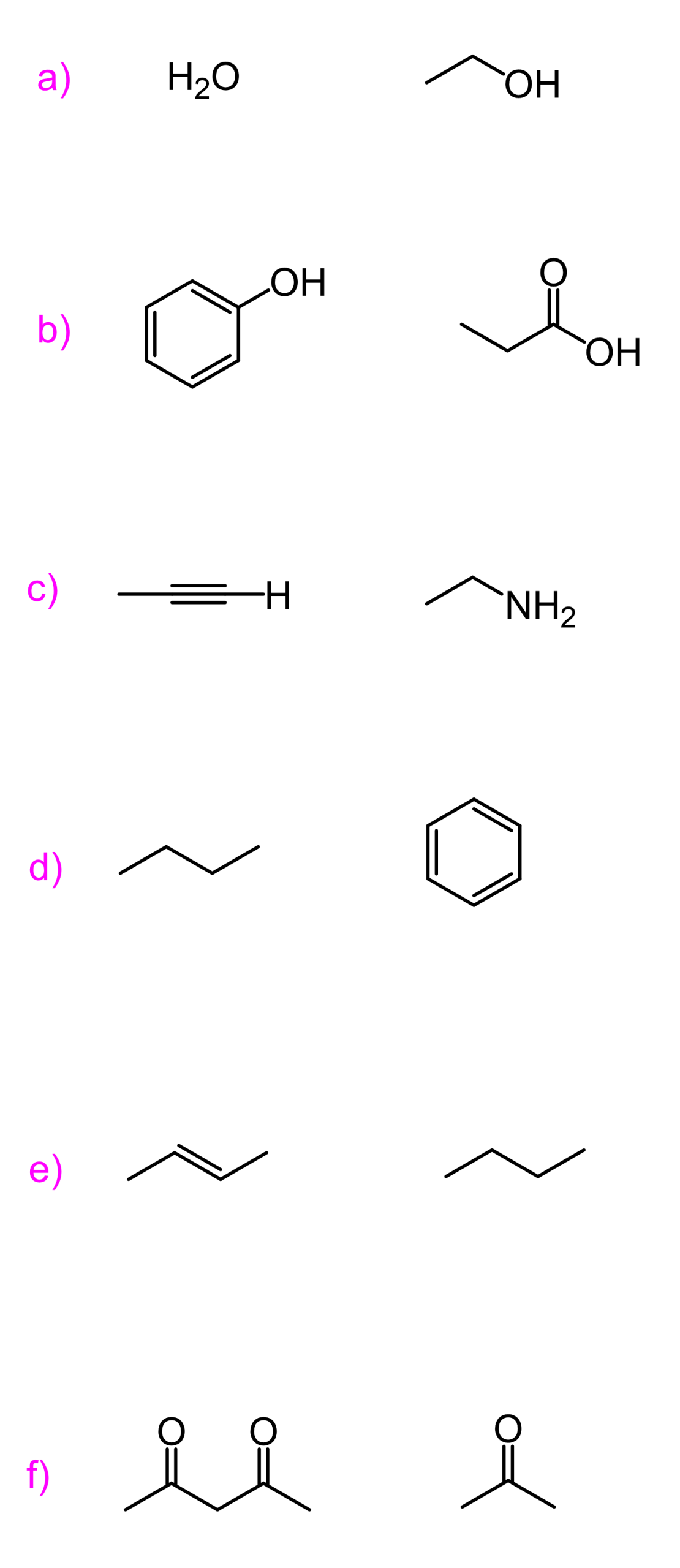

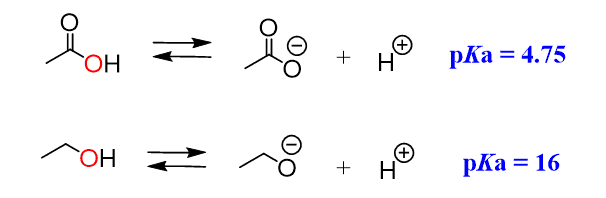

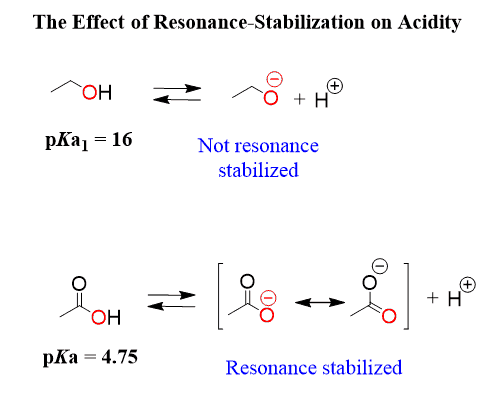

We can see, from the pKa values, that acetic acid is a much stronger acid than ethanol, even though upon dissociation, the negative charge ends up on the same element, which is oxygen:

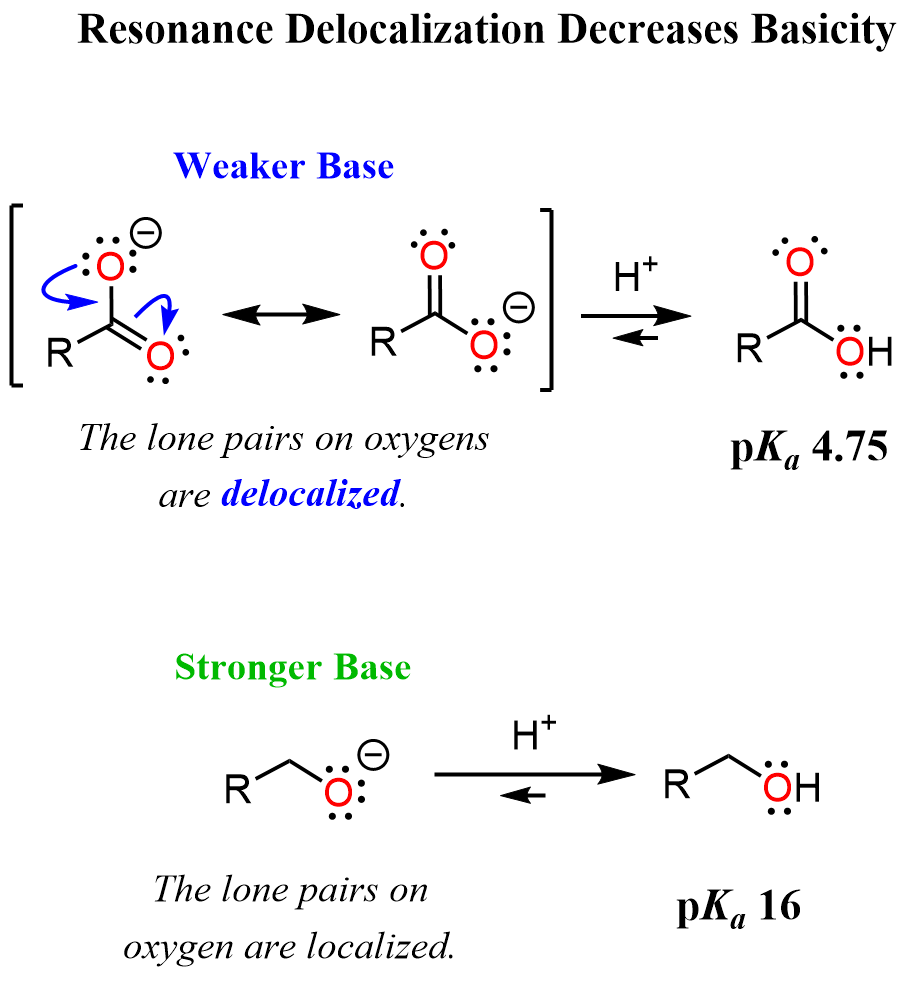

This is because the electrons on the oxygens of carboxylic acid are delocalized (in resonance with the other oxygen) and the negative charge is handled by both atoms, while the oxygen in the alcohol handles the negative charge alone:

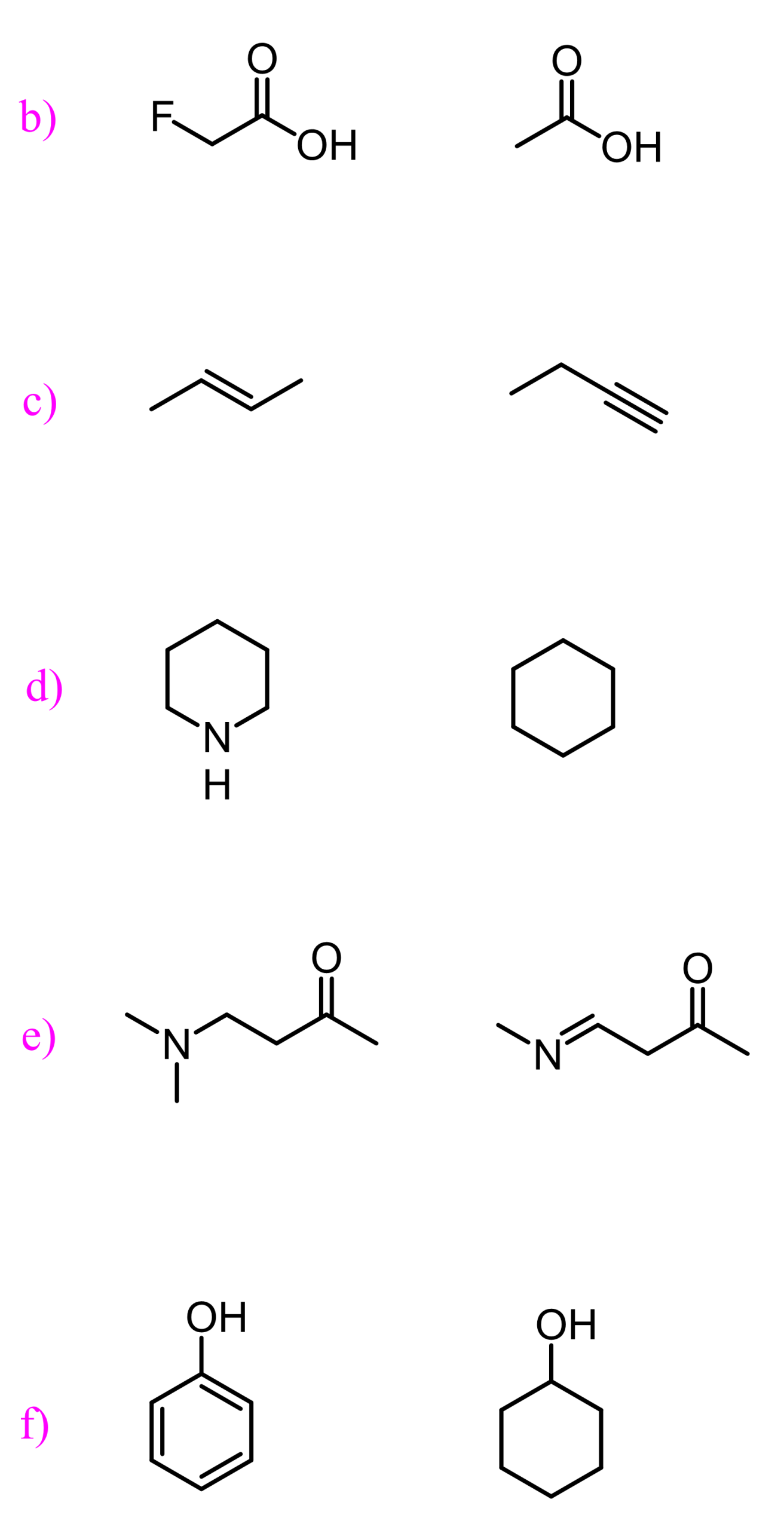

Another example of the resonance stabilization of the conjugate base, thus making the acid stronger, is phenol. Compared to cyclohexanol, it is again about a million times more acidic, which is again because of resonance stabilization of the conjugate base. Although this is a bit more complicated, as we also say that the lone pairs on phenol are not delocalized over the benzene ring, as that would disturb the aromaticity, but that is another topic, and a lot of you have probably not talked about aromatic compounds yet.

To keep this fair, another factor contributing to the increased acidity of phenol is the hybridization of the carbon atoms in the aromatic ring. These are sp2 hybridized and sp2 hybridized carbon atoms are more electronegative than sp3 carbons because they have more s character.

As a result, they have an electron-withdrawing inductive effect while the aliphatic carbons are electron donors. So, the sp2 carbon is more helpful in stabilizing the negative charge on the oxygen via an electron-withdrawing inductive effect (Recall the ARIO).

In general, the more s character, the more electronegative the atom is. These are the percentages of the s orbital (s-character) in each hybrid orbital:

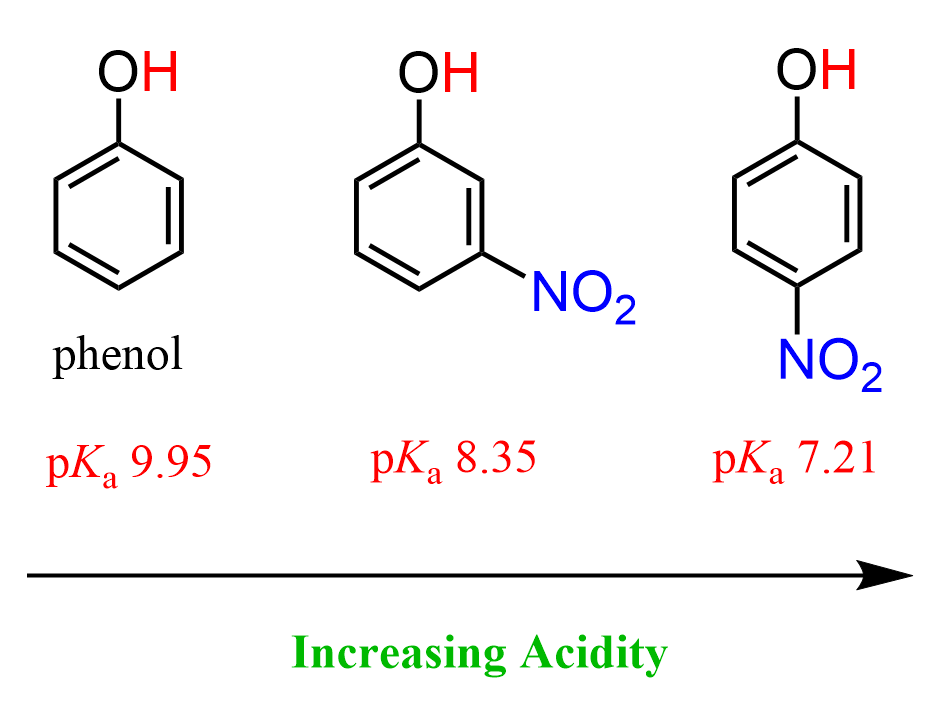

To have all these parameters identical and see what would be the effect of resonance electron withdrawing, we can also compare the acidity of phenol with nitrophenols. The nitro group contains a N=O pi bond, and it is a resonance-withdrawing group like, for example, different carbonyl derivatives, such as aldehydes, ketones, carboxylic acids, etc. This pi bond allows for a resonance stabilization of the negative charge that is formed upon the deprotonation of the OH group.

Both 3-nitrophenol (m-nitrophenol) and 4-nitrophenol (p-nitrophenol) are more acidic than phenol.

Notice that p-nitrophenol is also more acidic than m-nitrophenol, and that has to do with the fact it the nitro group in meta position can only stabilize the negative charge via inductive electron-withdrawing effect, whereas in p-nitrophenol, the negative charge is stabilized by both inductive and resonance effects.

You do not need to worry about the terms “meta”, para, “aromatic etc., if you have not reached the chapter of aromatic chemistry, which is an organic 2 topic.

The take-home message for you here is that resonance-withdrawing groups can stabilize the conjugate base by delocalizing its lone pairs, thus increasing the acidity of the compound. Once again, recall that the weaker/more stable the conjugate base, the stronger the acid.

Can Resonance Decrease Acidity?

This again is an Organic 2 topic, so feel free to skip it if you are on the acid-base and resonance chapters.

Yes, resonance-donating groups can decrease the acidity by supplying additional electron density to the atoms bearing the negative charge. And even before getting to the conjugate base, think about it this way: if a group pushes some electron density to, for example, an oxygen, it will be more reluctant to lose the proton connected to it and become negatively charged.

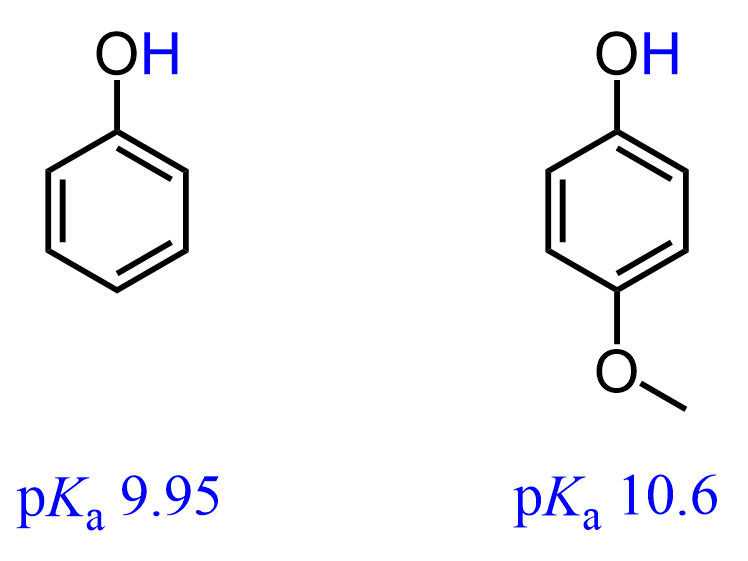

For example, 4-Methoxyphenol is less acidic than the phenol itself. Compare their pKa values:

This is because one of the lone pairs on the methoxy oxygen is in resonance with the π electrons of the aromatic ring, which allows it to donate additional electron density to the negatively charged oxygen:

This is an example of a positive mesomeric effect (+M) that ranges through several π bonds.

Both effects indeed exist, and the oxygen is electron-withdrawing by inductive, and electron-donating by mesomeric effect:

What you need to remember is that the resonance effect is generally more predominant, and thus, the electron-donating effect, in this case, is what predominates. Check the article “Resonance and Inductive Effects” for a more detailed discussion of this topic.

Resonance Effect on Basicity

We said the ethoxide ion will be considered as an example of a strong base, and we can see that by again comparing its stability with that of the acetate or any carboxylate ion. The lone pairs on the oxygen in the acetate ion are delocalized with the pi bond of the carbonyl group, which makes them less available to act as a base. On the contrary, the lone pairs in the ethoxide ion are only handled by one oxygen atom. This makes the ethoxide (any alkoxide) ion more basic as the negative charge is poorly stabilized:

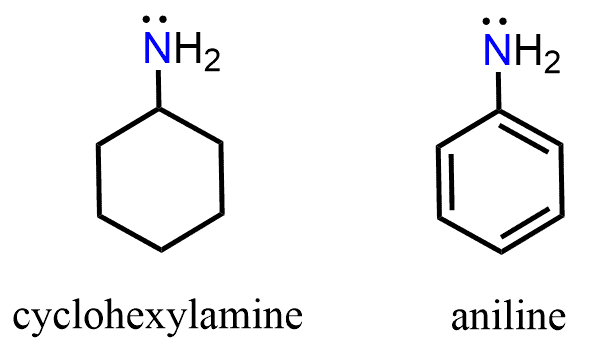

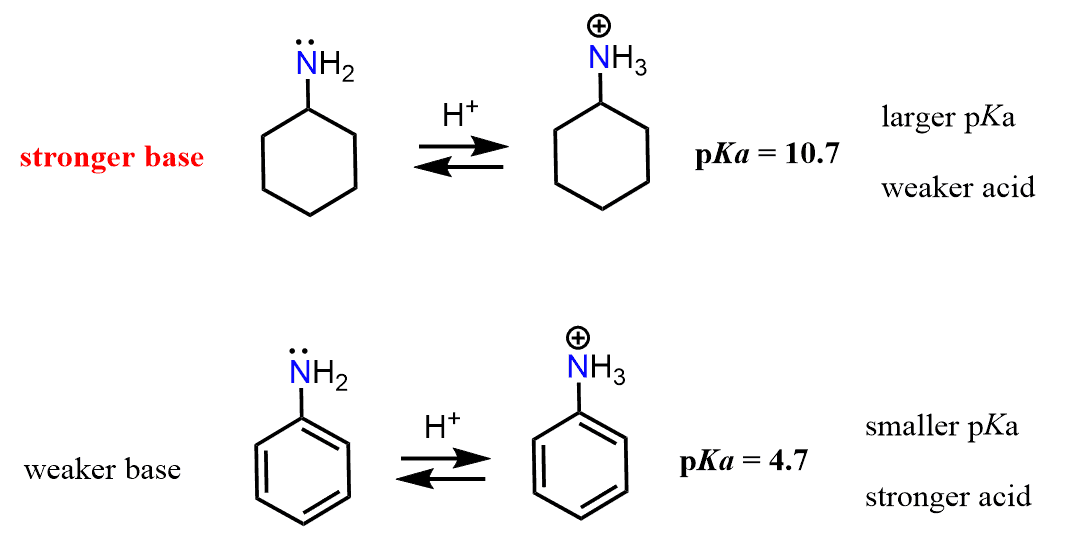

Basicity of Alkyl and Aryl Amines

Let’s compare the base strength of cyclohexylamine and aniline and state from the beginning that the former is a stronger base. So, you can take a moment to try finding an explanation for this observation:

Keep in mind that the base strength of the amine will increase with its readiness to donate the electron pair. Now, the lone pair on the nitrogen in ethylamine is “not doing anything” other than just sitting there, i.e., it is localized. The one in aniline, on the other hand, is next to an aromatic ring, which is a conjugated system, and if this lone pair can be part of the conjugate system, we can predict that it is not going to be as ready to accept a proton. And, in fact, the lone pair of nitrogen in aniline is delocalized on the benzene ring, and that is why aniline is less basic than ethylamine or most alkyl amines for that comparison.

And here as well, the pKa values support this reasoning. Because the pKa of CH3CH2NH3+ is higher than the pKa of C6H5NH3+, CH3CH2NH2 is a stronger base than C6H5NH2.

Like in the case of phenol, the sp2 hybridization of the nitrogen in aniline also contributes to its weaker basicity.

Basicity of Amines and Amides

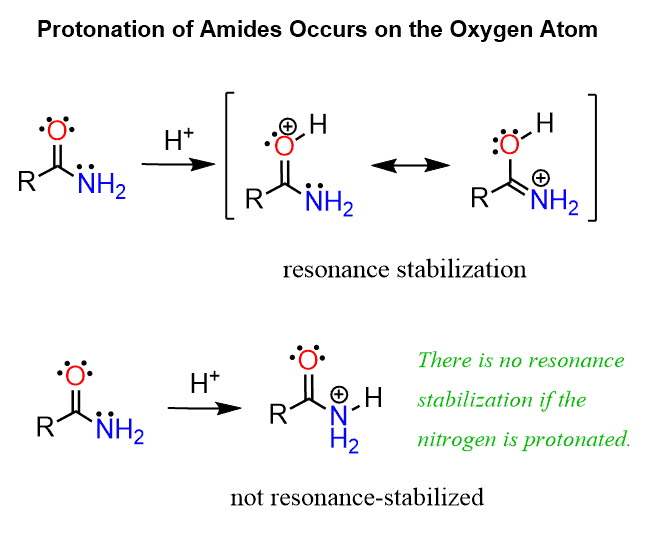

If we compare the structures of amines and amides, we can see that they are similar to what we discussed for the basicity of alkoxide (RO–) and carboxylate (RCOO–) ions. Amides are generally weaker bases than amines. The pKa of the conjugate acid of a typical amide is about 0.5-1, and there are two factors contributing to this decreased basicity. One is what we have already mentioned in a few examples, and that is the delocalized nature of the lone pair on nitrogen:

Because of these resonance configurations, the protonation of amides occurs on the oxygen rather than the nitrogen atom. Compare how the oxygen is resonance-stabilized by the lone pair of the nitrogen when it is protonated and the lack of this stabilization if the nitrogen were to be protonated:

The second factor decreasing the basicity going from amines to amides is the electron-withdrawing effect of the carbonyl group in the amide. Remember, the entire alpha carbon chemistry is based on this effect of the carbonyl group, which makes the ɑ proton significantly more acidic than in other hydrocarbons.

Basicity of Heterocyclic Aromatic Amines

This, once again, may not be something you talked about in the chapter on acid-base chemistry, so feel free to skip it if it sounds completely foreign. Although, to be fair, it is a discussion about resonance delocalization, or more accurately, the lack thereof, when there is no good alignment of p orbitals.

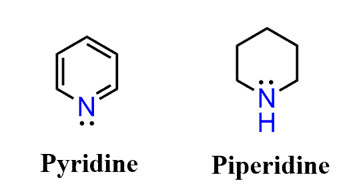

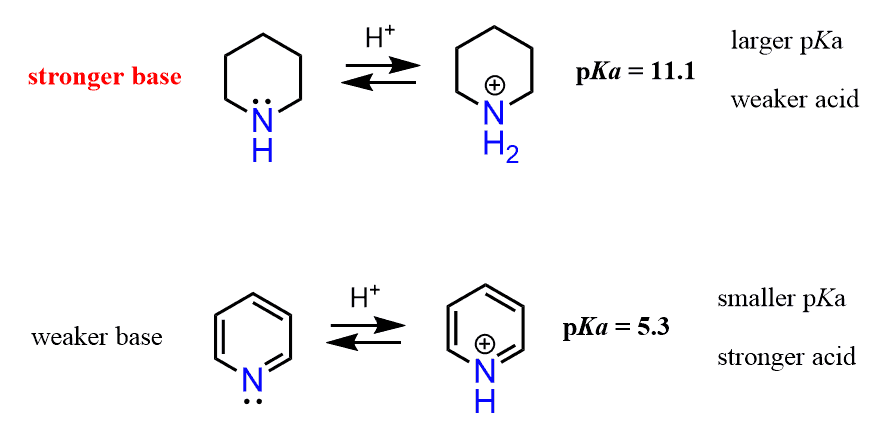

Let’s compare the basicity of pyridine and piperidine. One is an aromatic amine, and the other is a cyclic aliphatic amine.

From what we have discussed so far, it should look to you that pyridine is going to be the weaker base because of the aromatic ring. And that prediction is in fact accurate – pyridine is a lot weaker of a base than piperidine.

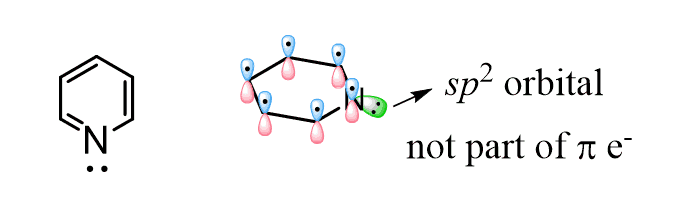

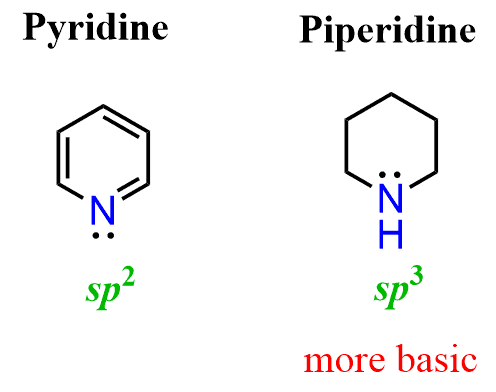

However, the effect of the aromatic ring here is not the same as in aniline. The big difference here, compared to the effect of the aryl ring on the basicity of aniline, is that the lone pair of pyridine is not delocalized over the aromatic system. It is localized since the electrons are in the sp2 orbital, and this orbital is at 90o to the p orbitals of the ring and cannot be part of the conjugated system.

Remember, in order to be conjugated, the orbitals must be parallel and not perpendicular. Now, if the lone pair is localized, what makes pyridine less basic than the one in piperidine?

The answer to this question is the hybridization of the nitrogen. As we mentioned earlier, sp2 orbitals have more s character than sp3 orbitals and therefore, they are more electronegative, which in turn makes them less basic. Notice that the nitrogen in piperidine is sp3 hybridized and thus it is more basic:

The next scenario would be an aromatic amine where the lone pair of the nitrogen is part of the aromatic system, i.e., it is delocalized.

One such good example is pyrrole.

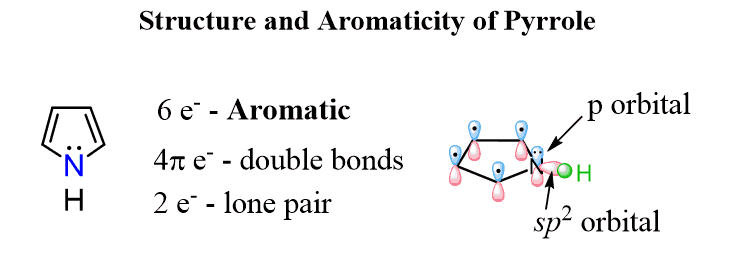

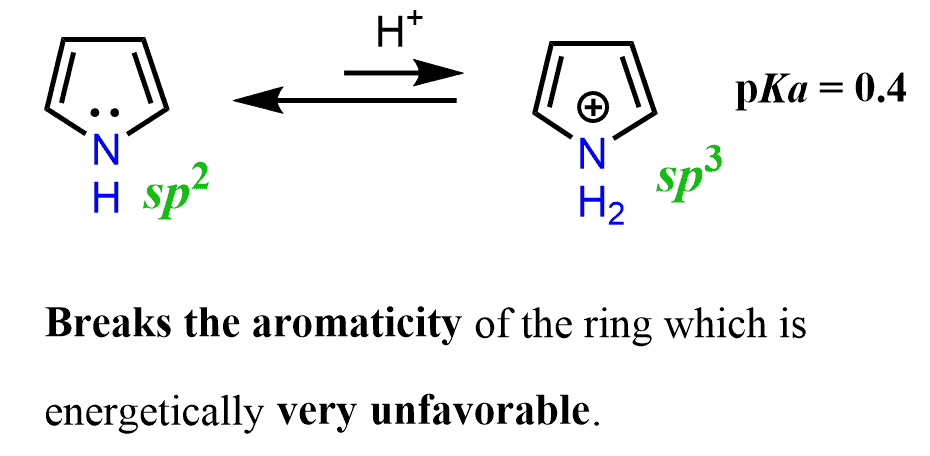

The nitrogen here looks to be sp3 based on the steric number (s.n. = 4: 3 bonds and a lone pair) but because the molecule “wants” to be aromatic”, it changes the hybridization to sp2 thus placing the lone pair in a p orbital and forming a cyclic, planar, fully conjugated system of 6 electrons:

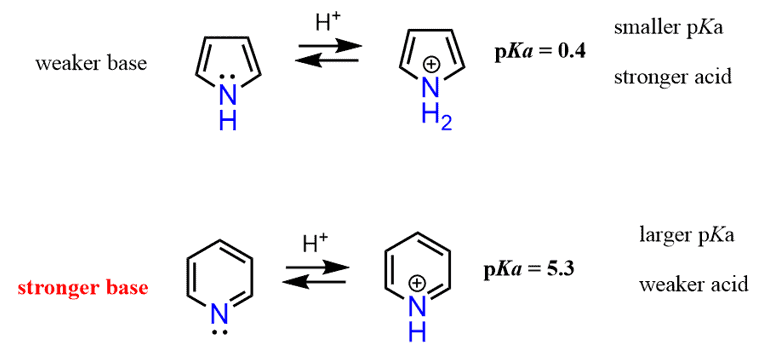

The lone pair on pyrrole, therefore, is delocalized, thus making a five-membered aromatic ring, and as expected, pyrrole is a much weaker base than pyridine.

Not only does the protonation of pyrrole occur less readily, but also the resulting structure breaks the aromaticity of the ring, which is energetically very unfavorable.

We have a more thorough discussion on the basicity of amines, which is more advanced and better-suited for the chapter on amines, as at that point, you’d have most of the chapters, including aromatic chemistry, covered. So, check that out as well if you are towards the middle or end of your organic chemistry 2 class.

Can Resonance Increase Basicity?

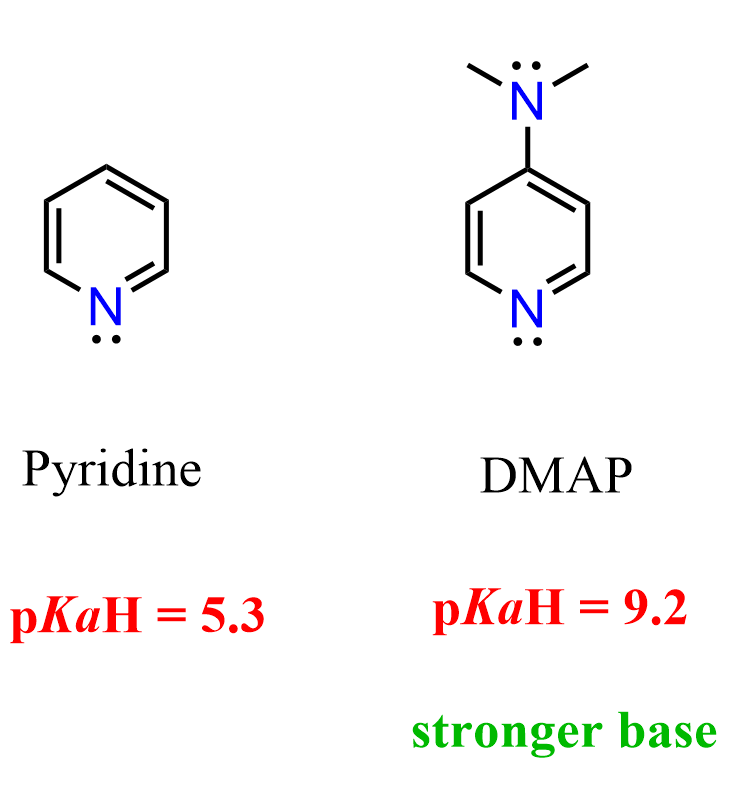

We’ve seen that the lone pair on the nitrogen in pyridine is delocalized over the aromatic system, and the pKₐH of pyridine is about 5.3. So, what happens if we add an electron-donating group such as a dimethylamino group to the ring?

The resulting compound is called 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), and it is quite a bit more basic than pyridine with a pKₐH of around 9.2.

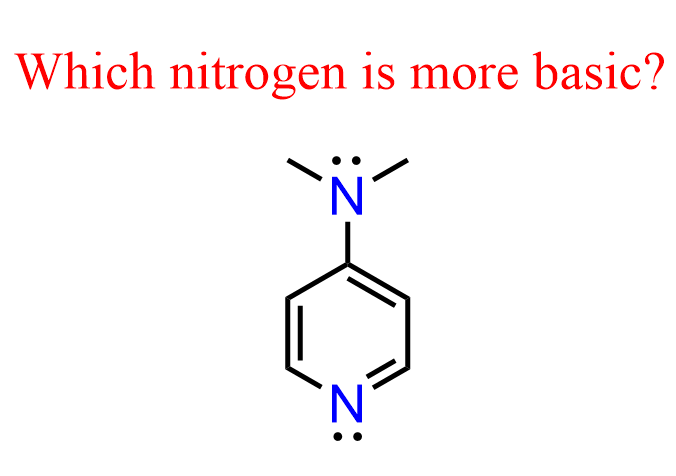

Perhaps the first question you wanted to answer is: Which nitrogen in DMAP is the base in this comparison?

What do you think?

To confirm that it’s the one in the ring, try protonating the dimethylamino group and see if the resulting structure can be stabilized. Remember what you know about significant and insignificant resonance forms.

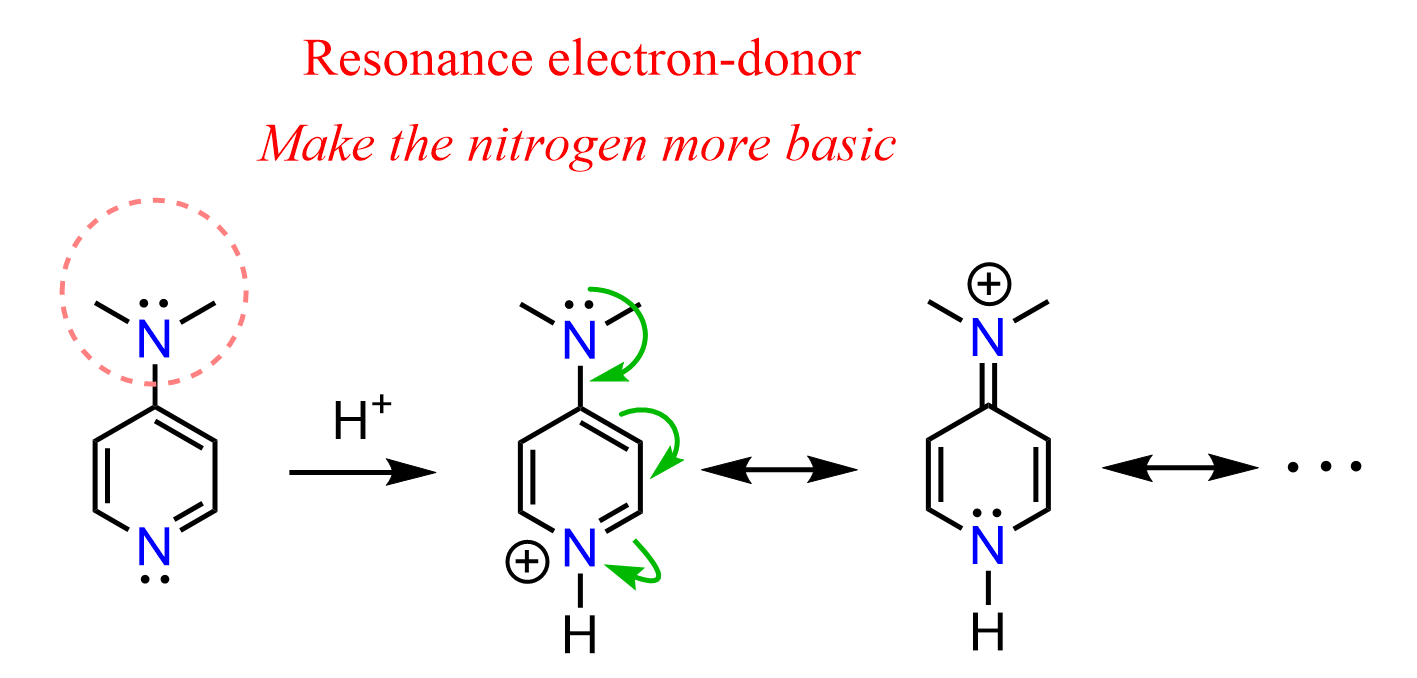

This increase in basicity is a result of the electron-donating resonance effect of the dimethylamino group, which stabilizes the protonated form of DMAP and makes it easier for the molecule to accept a proton. In other words, it makes DMAP a stronger base than pyridine.

We can see how the positive charge on the nitrogen is better delocalized thanks to the additional resonance contributed by the dimethylamino group by drawing the conjugate acid of DMAP:

This example shows that, as expected, electron-donating groups increase the basicity by stabilizing the conjugated acid of the base.

Inductive Effect on Acidity and Basicity

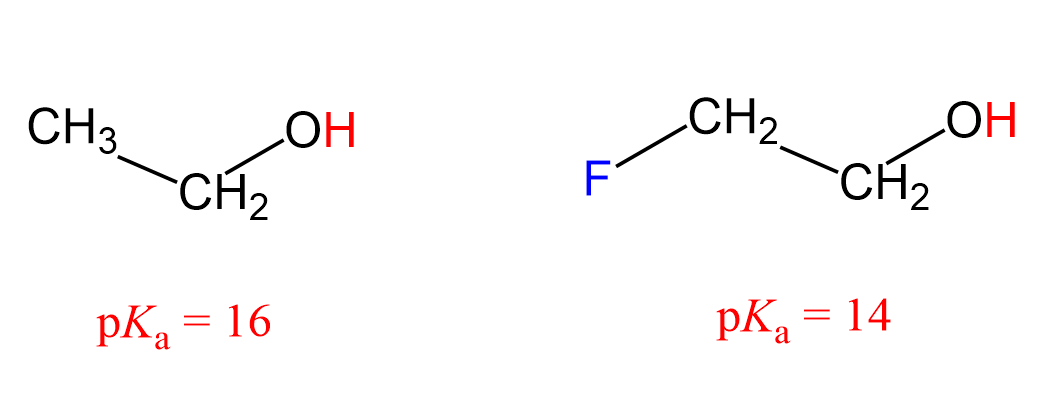

Basicity and acidity can also be affected by inductive effects. For example, 2-fluoroethanol is a stronger acid than ethanol, as seen from their pKa values:

What makes 2-fluoroethanol a stronger acid? The acid strength increases with better stabilization of the negative charge of its conjugate base, so what happens here is fluorine pulls the electron density from the negatively charged oxygen, thus stabilizing the conjugate base of the alcohol.

The way it works is that the F-C bond reduces the electron density of the carbon, which in turn does the same to the other carbon, and finally, the carbon connected to the oxygen helps it handle the negative charge by reducing its electron density:

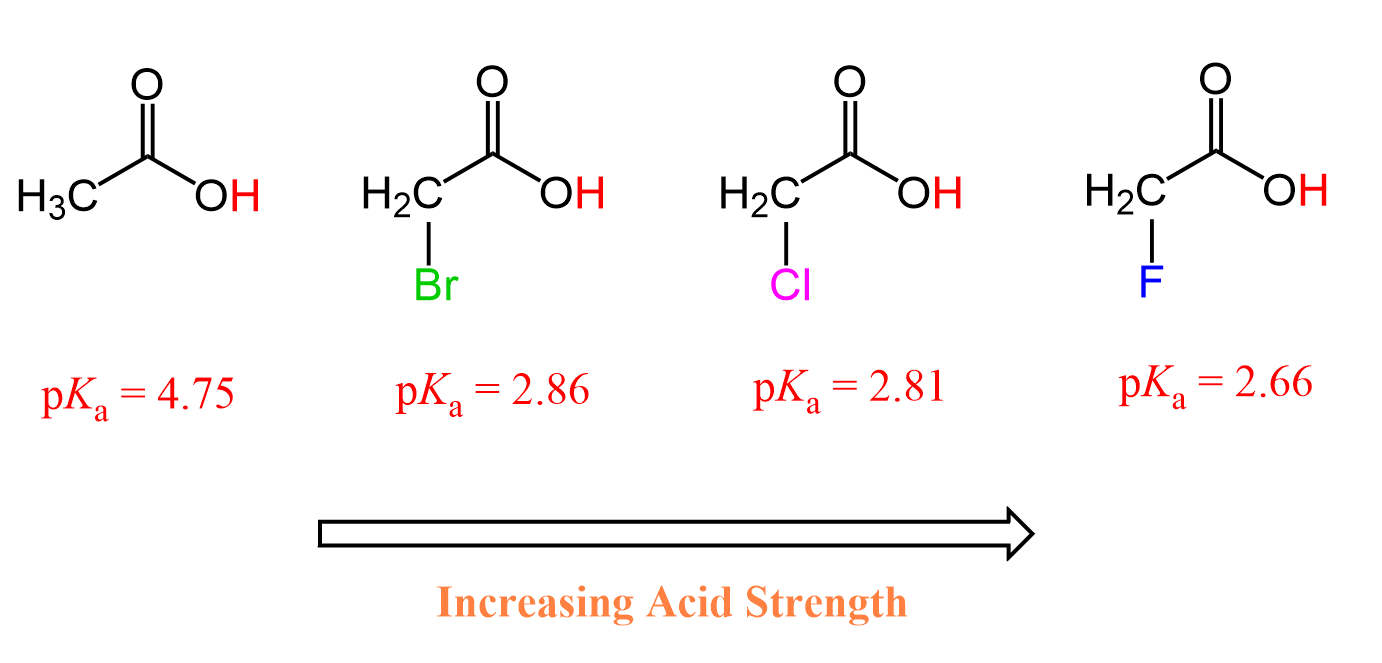

This pattern is very common and very well-studied for carboxylic acids. The presence of a halogen increases their acidity through the electron-withdrawing inductive effect. The greater the electronegativity of the halogen, the greater the inductive effect and thus the stronger the acid.

Fluoroacetic acid is stronger than chloroacetic acid, which is stronger than bromoacetic acid, which, in turn, is stronger than acetic acid by itself because the electronegativity of these halogens decreases in this order: F > Cl > Br.

Summary

Summarizing what we have discussed about the effect of resonance on acidity and basicity, we can say that:

Resonance has a significant impact on both acidity and basicity, and it usually works in favor of increased acidity and reduced basicity.

- In acids, resonance stabilizes the conjugate base by delocalizing the negative charge over multiple atoms. This makes it easier for the acid to lose a proton (H⁺), thereby increasing acidity.

- In bases, resonance stabilizes the lone pair by spreading it across multiple atoms. This reduces the base’s ability to donate the lone pair, which makes the base weaker or less reactive.

So, as a pattern, remember that resonance delocalization usually:

- Increases acidity (by stabilizing the conjugate base)

Decreases basicity (by stabilizing the lone pair and making it less available)

This is why molecules like phenol are much more acidic than cyclohexanol, and why amide groups are less basic than simple amines.

We have also discussed the inductive effect on acidity and basicity. The general pattern is the same: if it is an electron-donating effect, that would increase the basicity and decrease the acidity, whereas an electron-withdrawing effect increases the acidity and decreases the basicity.

Electron-donating groups (EDGs) push electron density toward a molecule, which:

- Increases basicity (makes lone pairs more available)

- Decreases acidity (makes it harder to lose a proton, since the conjugate base would be less stable)

Electron-withdrawing groups (EWGs) pull electron density away, which:

- Decreases basicity (lone pairs are less available)

- Increases acidity (conjugate base is stabilized by the withdrawal of electron density)