Nucleophile and Electrophile – The Terminology

From general chemistry, we know that covalent bonds between atoms are formed by sharing two electrons. So, let’s imagine separating these atoms by giving both electrons to only one of them. One becomes an electron-rich species, and the other becomes an electron-deficient species:

In simpler terms, we can say that one is negatively charged and the other is positively charged. What happens to particles with opposite charges? They attract each other because of Coulombic forces; therefore, they are going to unite by making the chemical bond again:

This is how chemical reactions work, and you might be surprised, but no matter how deep you go into the subject, it all boils down to how electron distributions create electron-deficient and electron-rich centers in organic molecules, causing them to react in predictable patterns.

So, memorize the simple “Negatives react/attack positives” pattern to get an idea of what is going to happen in a chemical reaction. The “negatives” are nucleophiles, and the “positives” are the electrophiles.

Nucleophiles

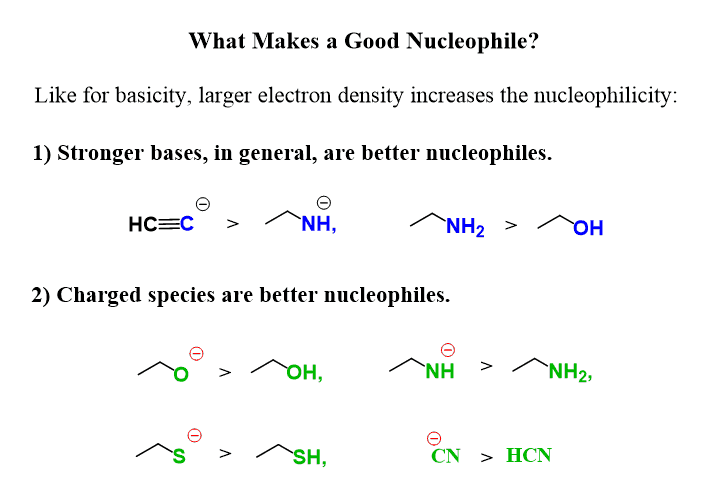

Nucleophiles are species that donate an electron pair to form a new covalent bond. They are attracted to positively charged or electron-deficient atoms-typically carbon atoms connected to electronegative elements like oxygen or halogens. In simple terms, nucleophiles are the “electron-rich attackers” in a reaction.

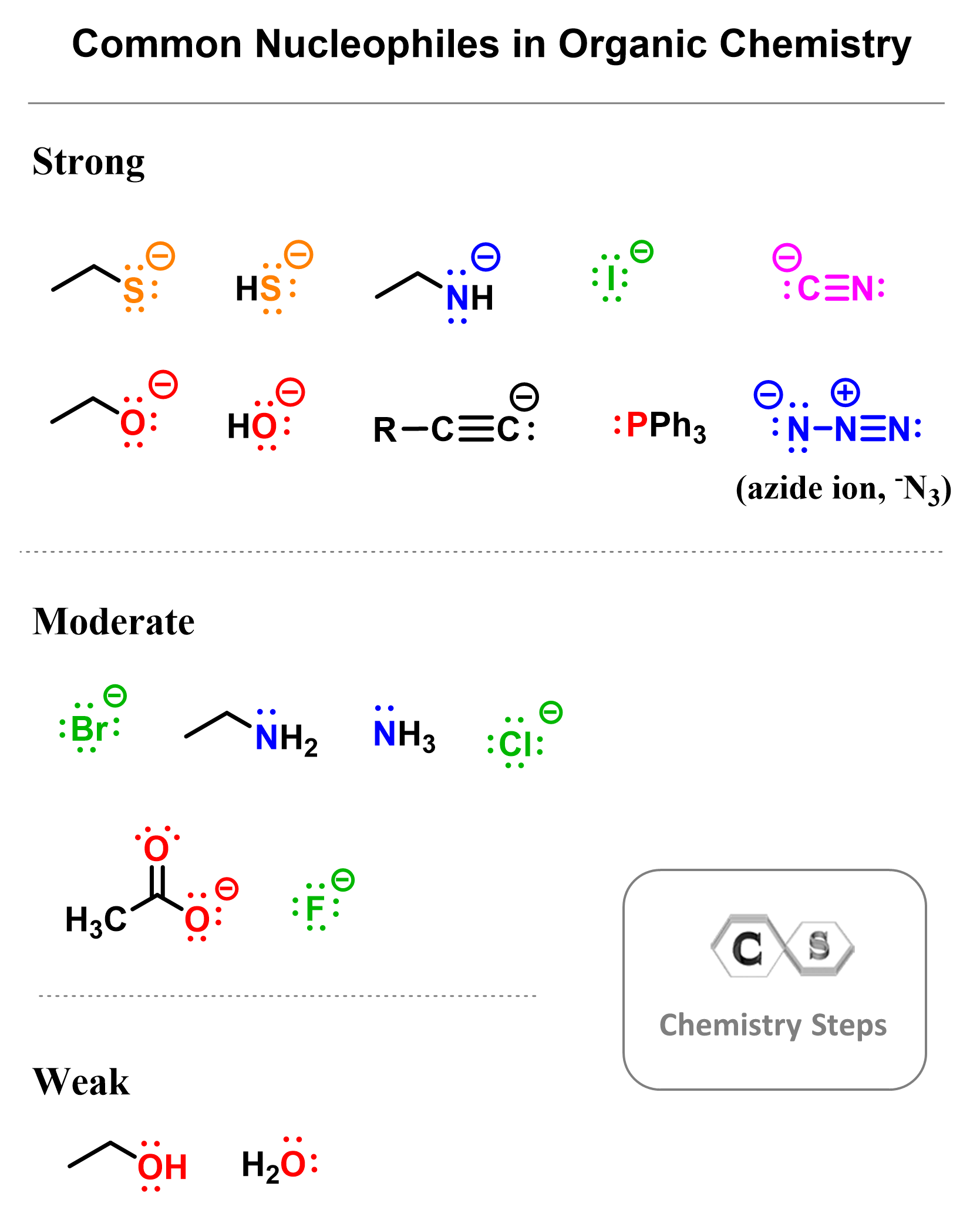

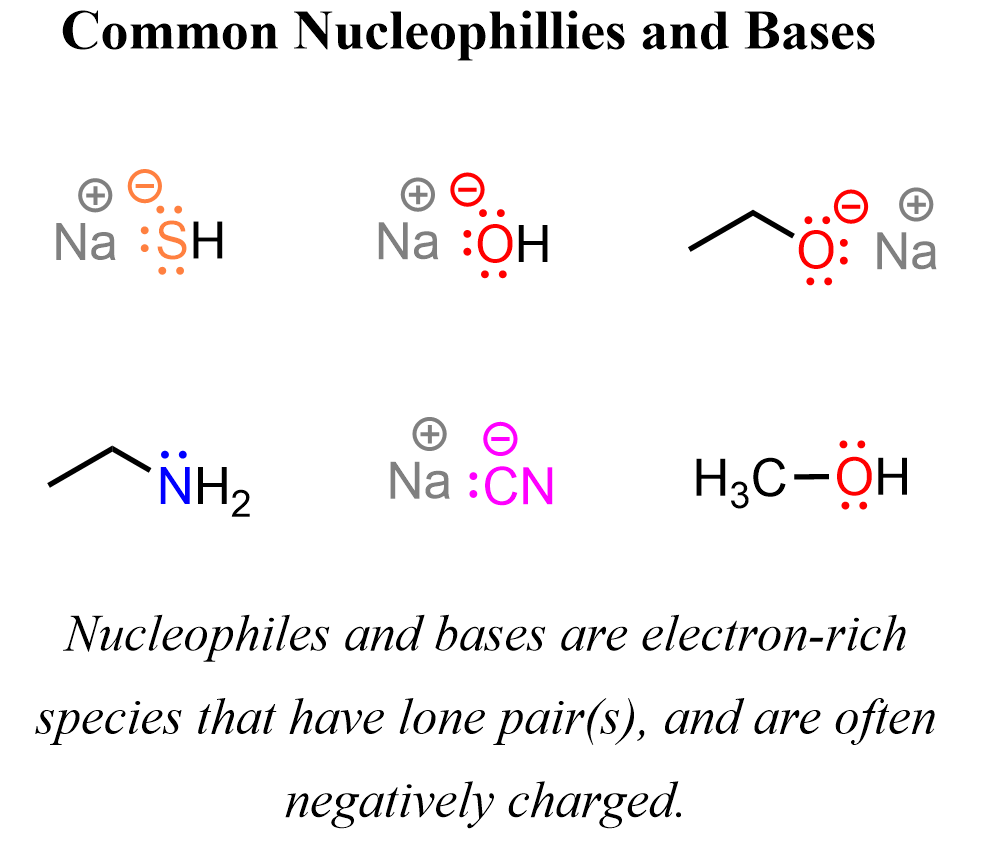

Here are some examples of common nucleophiles in organic chemistry:

Notice that nucleophiles do not have to be negatively charged – they may, but it is not a requirement. On the other hand, they all have a lone pair(s) of electrons, which makes them electron-rich and reactive towards an electrophile.

Electrophiles

Electrophiles are species that accept an electron pair to form a new covalent bond. They are electron-deficient and are attracted to negatively charged or electron-rich atoms-typically nucleophiles. In other words, electrophiles are the “electron-loving” or “positive” centers in a reaction.

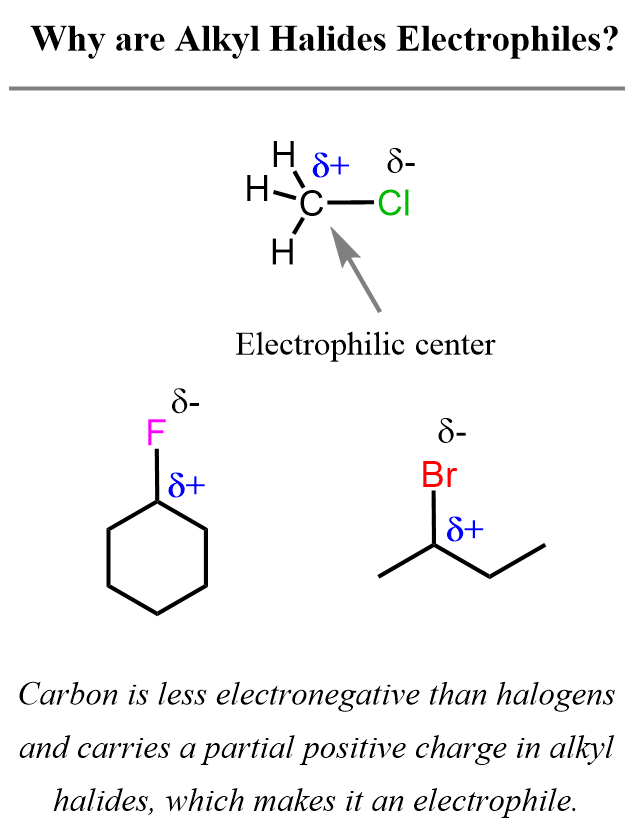

Like the nucleophiles, electrophiles do not have to be positively charged – they may simply contain a carbon atom with a polar covalent bond. This is, in fact, the most common electrophilic structure you will see in organic chemistry 1 – a carbon atom connected to a halogen.

These are called alkyl halides, and they are electrophilic because the carbon-halogen bond is polarized: the halogen is more electronegative and pulls electron density away from the carbon, leaving it partially positive (δ+). That makes the carbon an electron-deficient center, ready to be attacked by a nucleophile.

How Nucleophiles and Electrophiles React

Ok, so the interaction between positively charged and negatively charged species is quite straightforward to understand, and hopefully it continues to be when we switch to “organic chemistry” terms. Instead of saying electron-deficient, positively charged, electron-rich or negatively charged, we call them electrophiles (likes electrons), and nucleophiles (likes the nucleus, which is positively charged).

For example, here is an illustration of a reaction between a nucleophile and an electrophile:

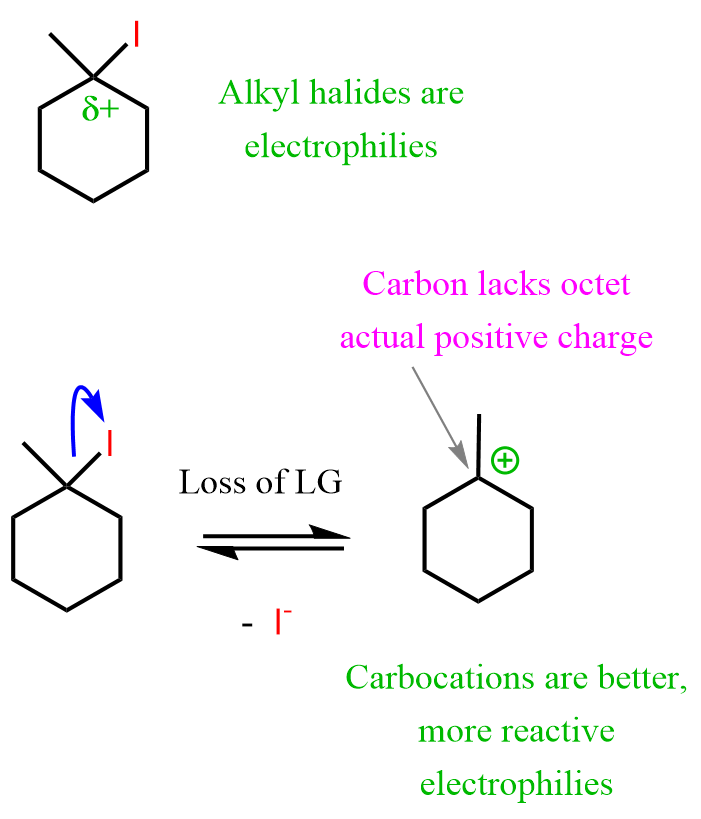

The chloride ion is the nucleophile because it is negatively charged, and the carbocation is the electrophile because it has an electron-deficient, positively charged carbon.

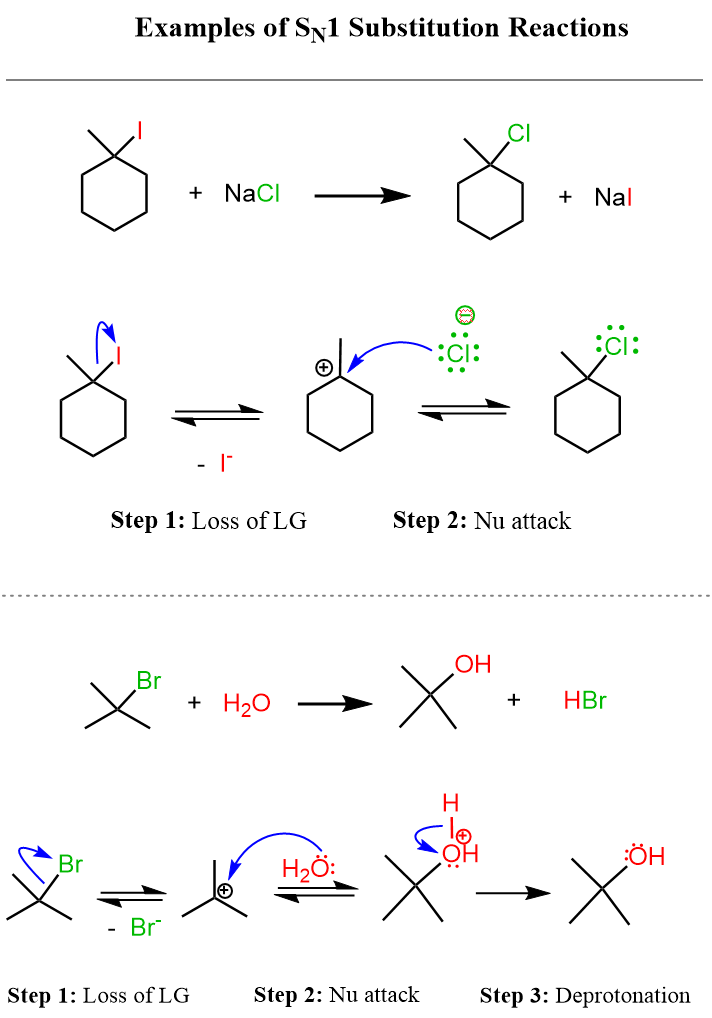

Now, this is a simplified fragment of a typical reaction known as an SN1 nucleophilic substitution reaction. It’s simplified because the carbocation doesn’t exist on its own – the carbon is initially connected to a halogen, and it only becomes positively charged once the bond with the halogen is broken.

Here is the complete mechanism of this SN1 reaction, together with one where water serves as the nucleophile:

You do not have to worry about all the details in these reactions for now if you are just starting learning about nucleophiles and electrophiles. You can read the articles “Substitution and Elimination Reactions” and “Introduction to Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions” to start getting into the details of these reactions.

Curved Arrows

Notice that we show the breaking and making of chemical bonds with curved arrows. These are the language of organic chemistry, and it’s very important to understand how to use them. We have a separate post on Curved Arrows, so check it out if you need to refresh this concept. In short, remember that curved arrows show the movement of electrons, always starting from an electron-rich site (like a lone pair or a bond) and pointing toward an electron-poor site where a new bond will form.

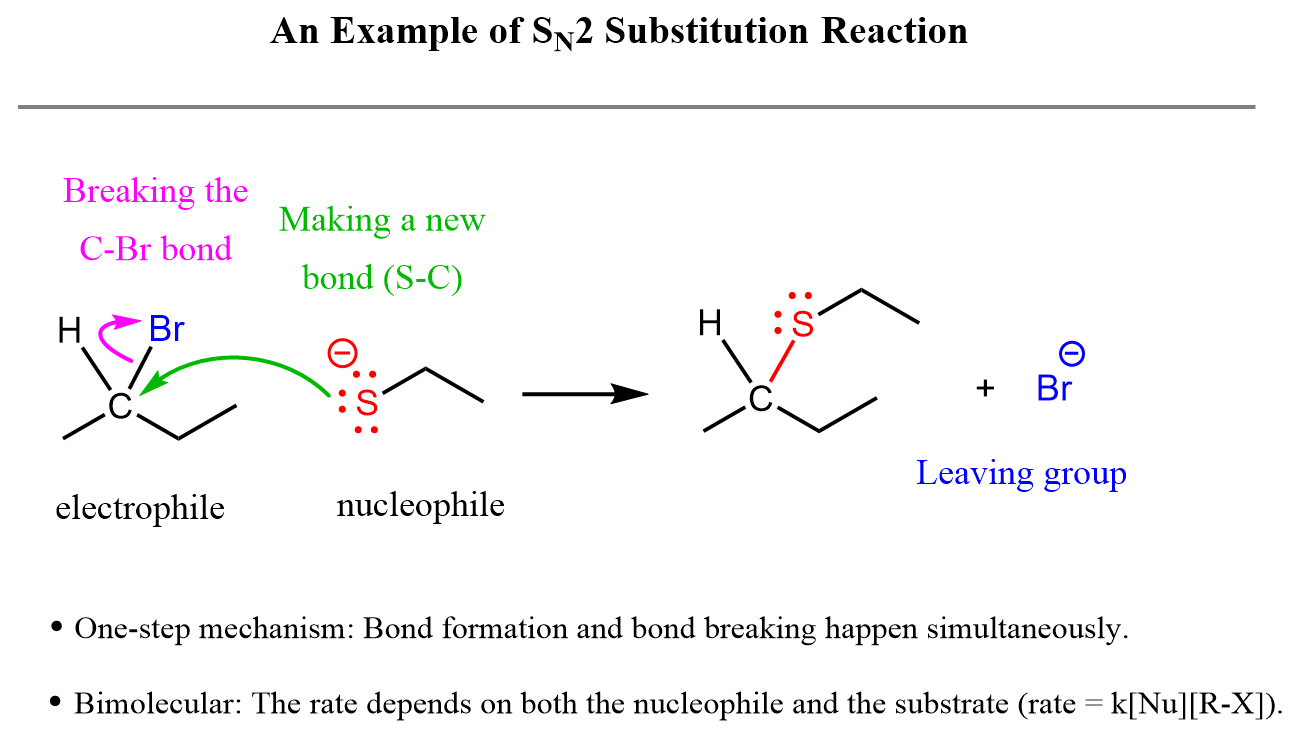

Nucleophile and Electrophile in SN2 Reactions

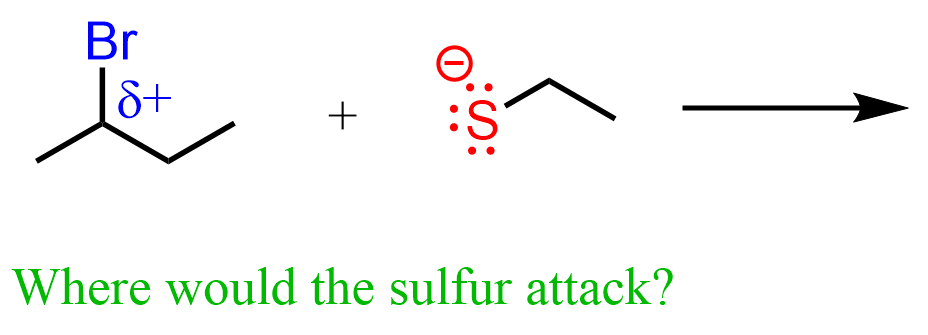

Let’s also consider another reaction between an alkyl halide and a thiolate ion – a nucleophile due to the presence of a negatively charged sulfur.

You may have a good shot guessing what atoms will be attracted if we mix, let’s 2-bromobutane with a thiolate ion (R–S⁻), such as ethanethiolate:

Yes, you are absolutely right, the negatively charged sulfur is going to attack the carbon with a partial positive charge.

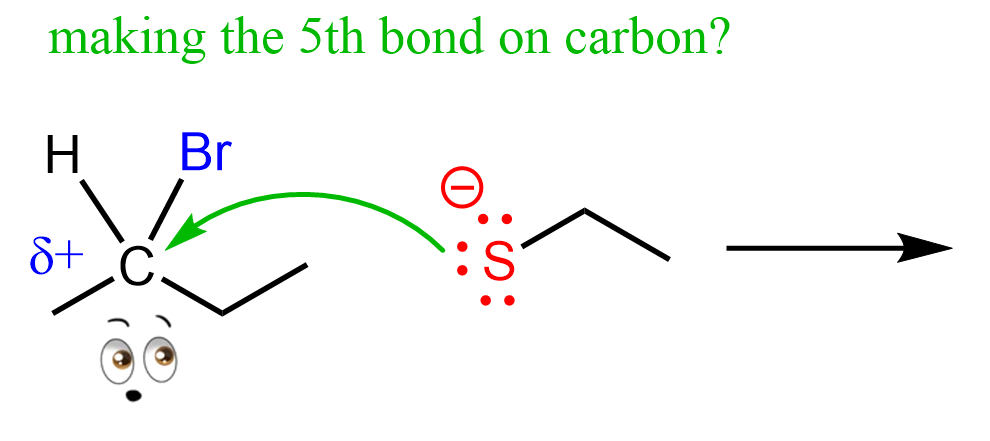

Now, by doing so, it provides electrons to the carbon, which means it is making a new covalent bond. So, what do you think is going to happen to the carbon? Is it going to have five bonds (don’t forget about omitted hydrogens in bond line structures)?

We know that carbon cannot have five bonds, so to make this bond, it must break one of the four bonds that the carbon already has, and it turns out, the easiest is the one with the halogen:

Unlike the ones shown above (SN1), the nucleophile here does not wait for the C–Br bond to break before it attacks the electrophilic carbon atom. Instead, because it is negatively charged, thus a stronger nucleophile it attacks the carbon while it is still connected to the bromine and breaks the C–Br bond by making a new C–S bond.

This is called the SN2 nucleophilic substitution reaction, which is characteristic of strong nucleophiles. You can read more about the principle, mechanism, stereochemistry, and lots of practice problems on the SN2 mechanism here.

Counterions

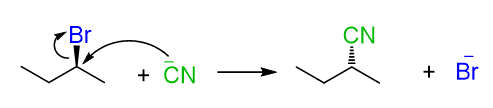

We have mentioned that carbocations do not just exist on their own, and this statement is true for any ions. For example, here is a classical SN2 reaction between 2-bromobutane (electrophile) and cyanide ion (nucleophile) .

Keep in mind that the cyanide ion does not exist in solution by itself – there is always a counterion, most often Na⁺ , because of its affordable pricing.

The reason the counterion is not shown in reaction mechanisms is that it usually does not participate in the reaction; it’s simply present to balance the charge.

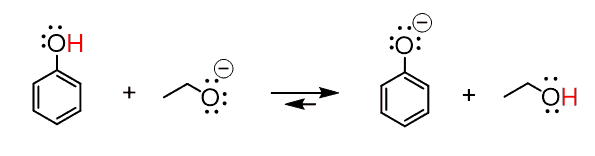

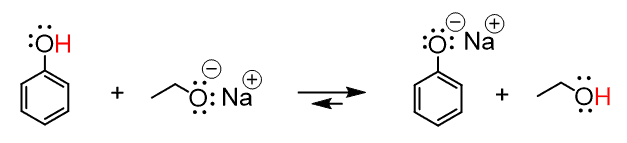

Another example where the counterion is typically omitted is in an acid–base reaction between phenol and sodium ethoxide (NaOEt). Here, Na⁺ is again present in the solution but does not affect the electron flow or outcome of the reaction, so it is left out for simplicity.

Of course, we can also show the reaction by including the counterion:

Here are some of the nucleophiles listed at the beginning of the post with a Na⁺ counterion.

Carbonyl and Nitrile Electrophiles

Other common electrophilic centers are those where the carbon is connected to oxygen or nitrogen through a double or a triple bond, respectively. These are called carbonyl (C=O) and nitrile (C≡N) electrophiles. The carbon in both functional groups is electron-deficient because the more electronegative oxygen or nitrogen atom pulls electron density away from it, creating a partial positive charge on the carbon. This makes the carbon susceptible to attack by nucleophiles.

Reactions involving these electrophiles typically proceed through a nucleophilic addition–elimination mechanism, which is different from the SN1 and SN2 substitution reactions discussed earlier.

Nonetheless, notice what is common in all these reactions: we have a carbon atom connected to an electronegative atom, which makes it partially positively charged, and therefore an electron-rich species (nucleophile) can attack it.

The addition-elimination mechanism and the chemistry of carbonyl and nitrile compounds in general are usually introduced in Organic Chemistry II.

Summarizing Nucleophiles and Electrophiles

In organic chemistry 1, you will hear the terms nucleophile and electrophile quite often. These are most commonly discussed in the context of SN1 and SN2 nucleophilic substitution reactions.

In a broad sense, you can visualize nucleophiles as the “–” (negative )species and electrophiles as the “+” (positive) species in the diagram.

Nucleophiles aren’t always negatively charged-they just need lone pair electrons to attack electrophiles. However, negatively charged nucleophiles are more reactive and are called strong or good nucleophiles.

Electrophiles aren’t always fully positive-they often have a carbon atom made partially positive by a polar covalent bond, such as in alkyl halides.

Most nucleophiles contain an oxygen, sulfur, and nitrogen atom, whether negatively charged or not.

Electron-rich species (nucleophiles) seek electron-deficient centers (electrophiles), following the simple principle: “Negatives react/attack positives.”

Check Also

- Introduction to Alkyl Halides

- Nomenclature of Alkyl Halides

- Substitution and Elimination Reactions

- Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions – An Introduction

- All You Need to Know About the SN2 Reaction Mechanism

The SN2 Mechanism: Kinetics, Thermodynamics, Curved Arrows, and Stereochemistry with Practice Problems - The Stereochemistry of SN2 Reactions

- Stability of Carbocations

- The SN1 Nucleophilic Substitution Reaction

- Reactions of Alkyl Halides with Water

- The Stereochemistry of the SN1 Reaction Mechanism

- The SN1 Mechanism: Kinetics, Thermodynamics, Curved Arrows, and Stereochemistry with Practice Problems

- Steric Hindrance in SN2 and SN1 Reactions

- Carbocation Rearrangements in SN1 Reactions with Practice Problems

- Ring Expansion Rearrangements

- Ring Contraction Rearrangements

- When Is the Mechanism SN1 or SN2?

- Reactions of Alcohols with HCl, HBr, and HI Acids

- SOCl2 and PBr3 for Conversion of Alcohols to Alkyl Halides

- Alcohols in SN1 and SN2 Reactions

- How to Choose Molecules for Doing SN2 and SN1 Synthesis-Practice Problems

- Exceptions in SN2 and SN1 Reactions

- Nucleophilic Substitution and Elimination Practice Quiz

- Reactions Map of Alkyl Halides