We learn in General Chemistry that the octet rule states that atoms tend to form bonds in such a way that they are surrounded by eight electrons in their outer (valence) shell.

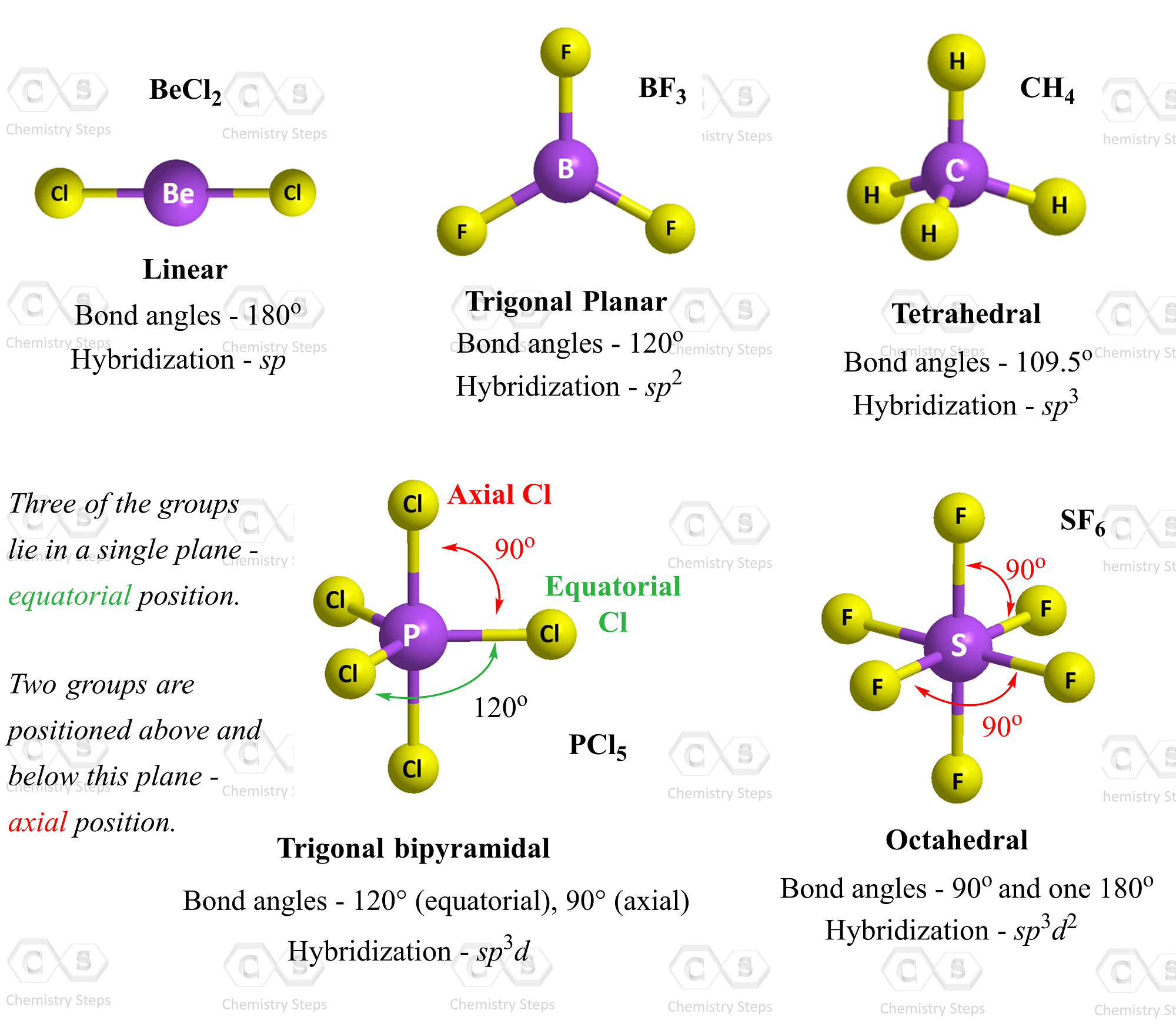

It is a great rule, of course, but let’s for a moment think of how many exceptions we saw starting from hydrogen and getting to 3rd-row elements such as sulfur, phosphorus etc., where geometries like trigonal bipyramidal and octahedral become quite common.

(🤫 A heads up – we are going to forget the geometries with more than four groups ☝️)

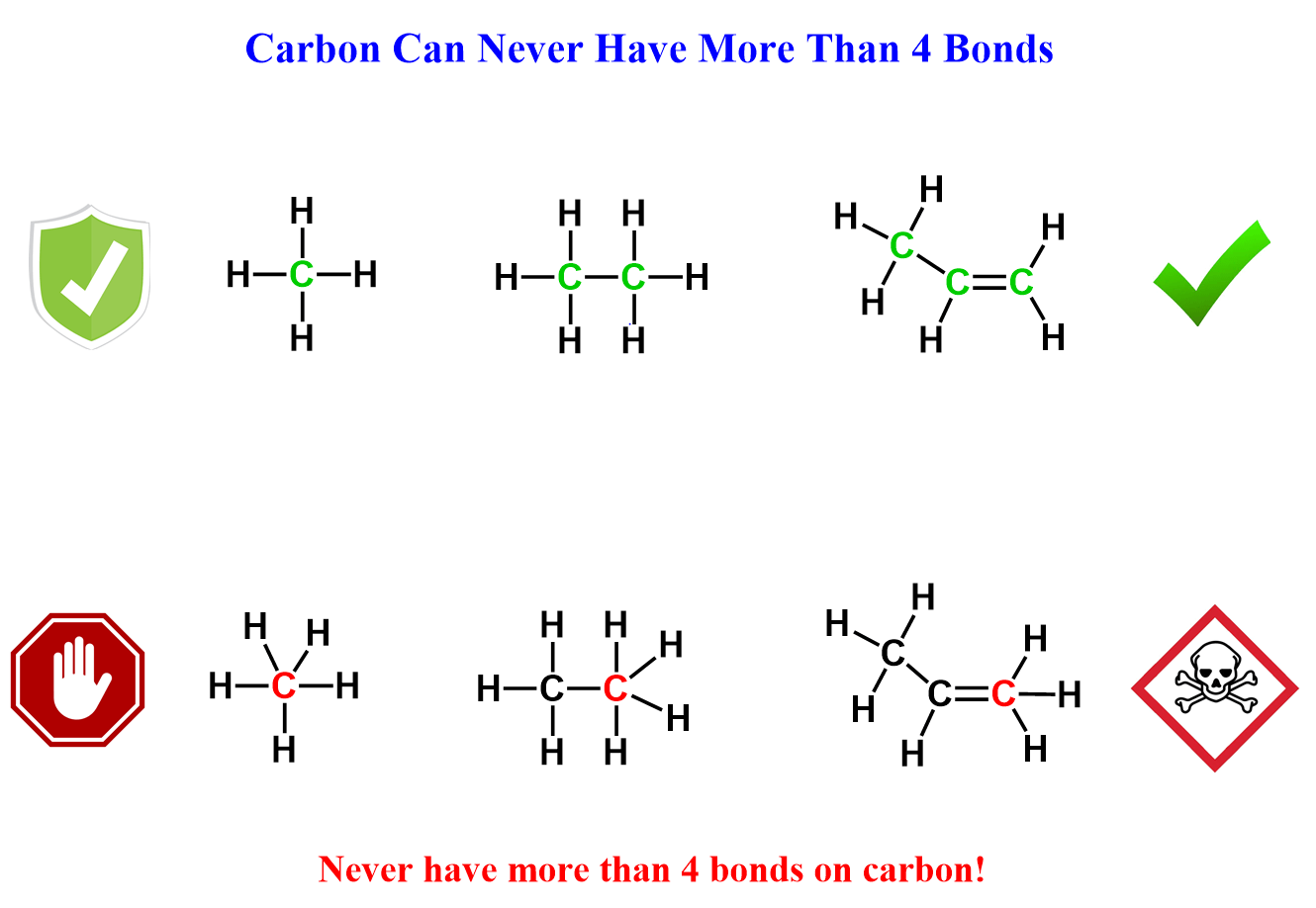

So, like it or not, the octet rule has more exceptions than actual obedience. Organic chemistry is the chemistry of carbon, which, being a second-row element in the fourth group, can only have a maximum of 4 bonds or a sum of bonds and lone pairs making 4.

Therefore, what is important for us to remember is that carbon, and other second-row elements, N, O, F, and the rest of the halogens, can never exceed an octet. That is the octet rule you need to know for organic chemistry.

The implication of this is that carbon can never have more than four bonds, so make this a golden rule for the start of your organic class:

The octet rule of organic chemistry, which we just formulated – C, N, O, F cannot exceed octet, brings another good news.

Geometry of Organic Molecules

In Organic Chemistry, we do not deal much with third-row elements, and the most branched geometry we get to is the tetrahedral. Once again, this is because carbon and the other second-row elements cannot have more than eight electrons around them. For carbon specifically, we have mentioned that it can have a maximum of 4 bonds, or a combination of bonds and lone pairs.

So, make sure to refresh the VSEPR theory up to Steric Number 4 – the tetrahedral geometry:

This also means you will only cover the sp, sp2, and sp3 hybridization models, so go over this post as well.

Bonding Patterns in Organic Chemistry

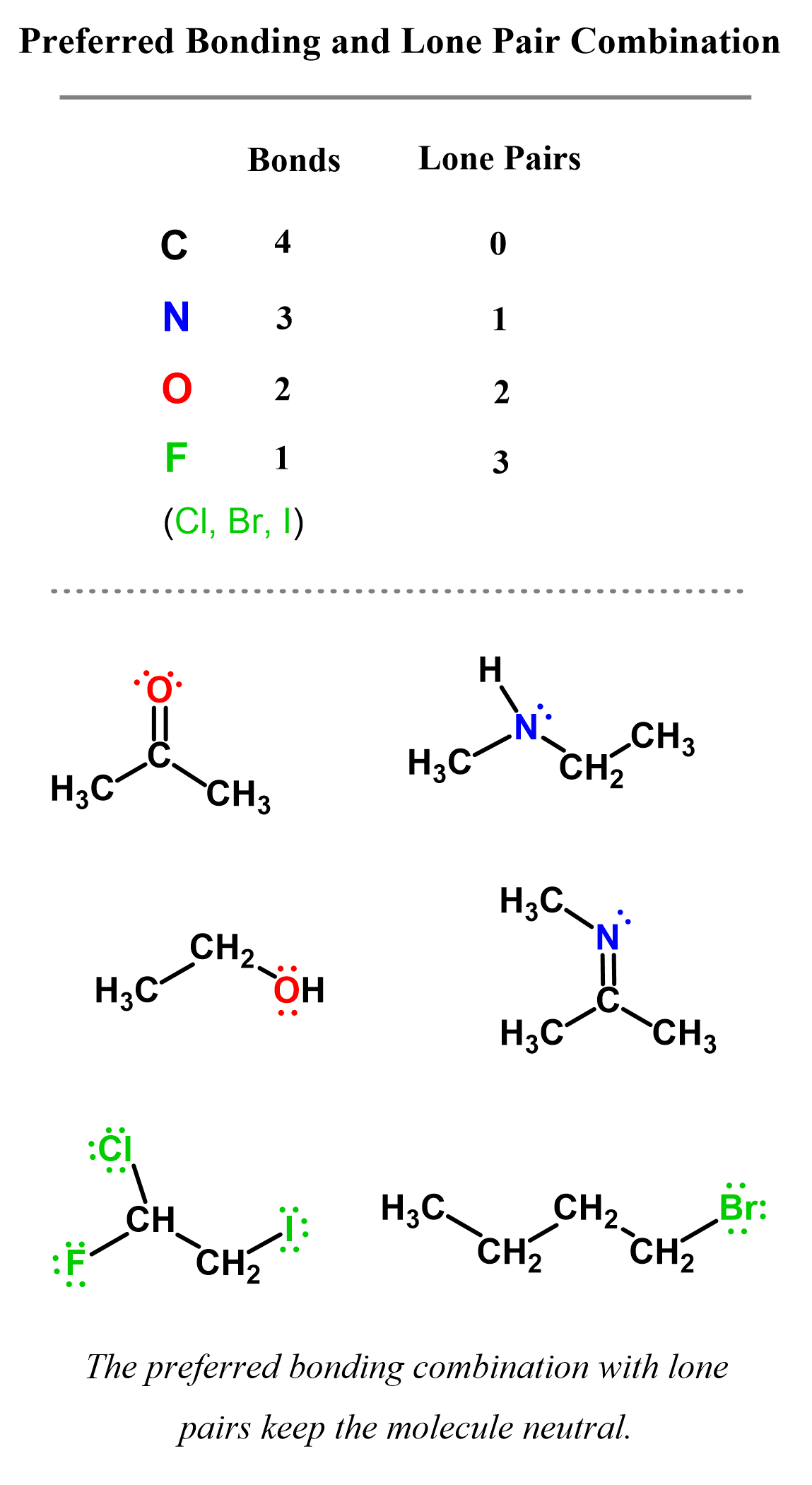

In neutral molecules, carbon always has four bonds, and this can be either four single bonds or a multiple bond, such as a double or triple bond. The image below summarizes the common bonding patterns of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and halogens in neutral molecules:

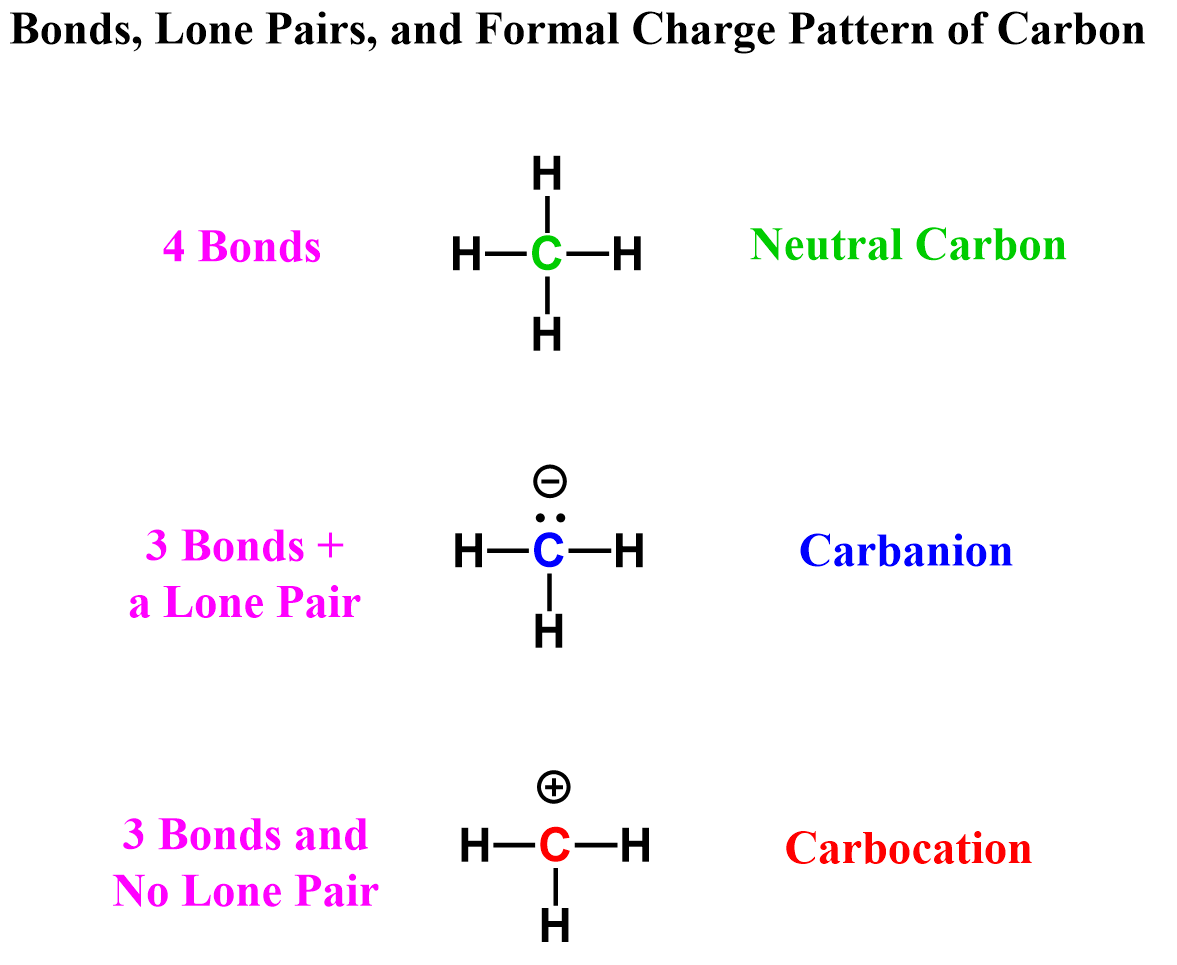

The question is: Can carbon have three bonds?

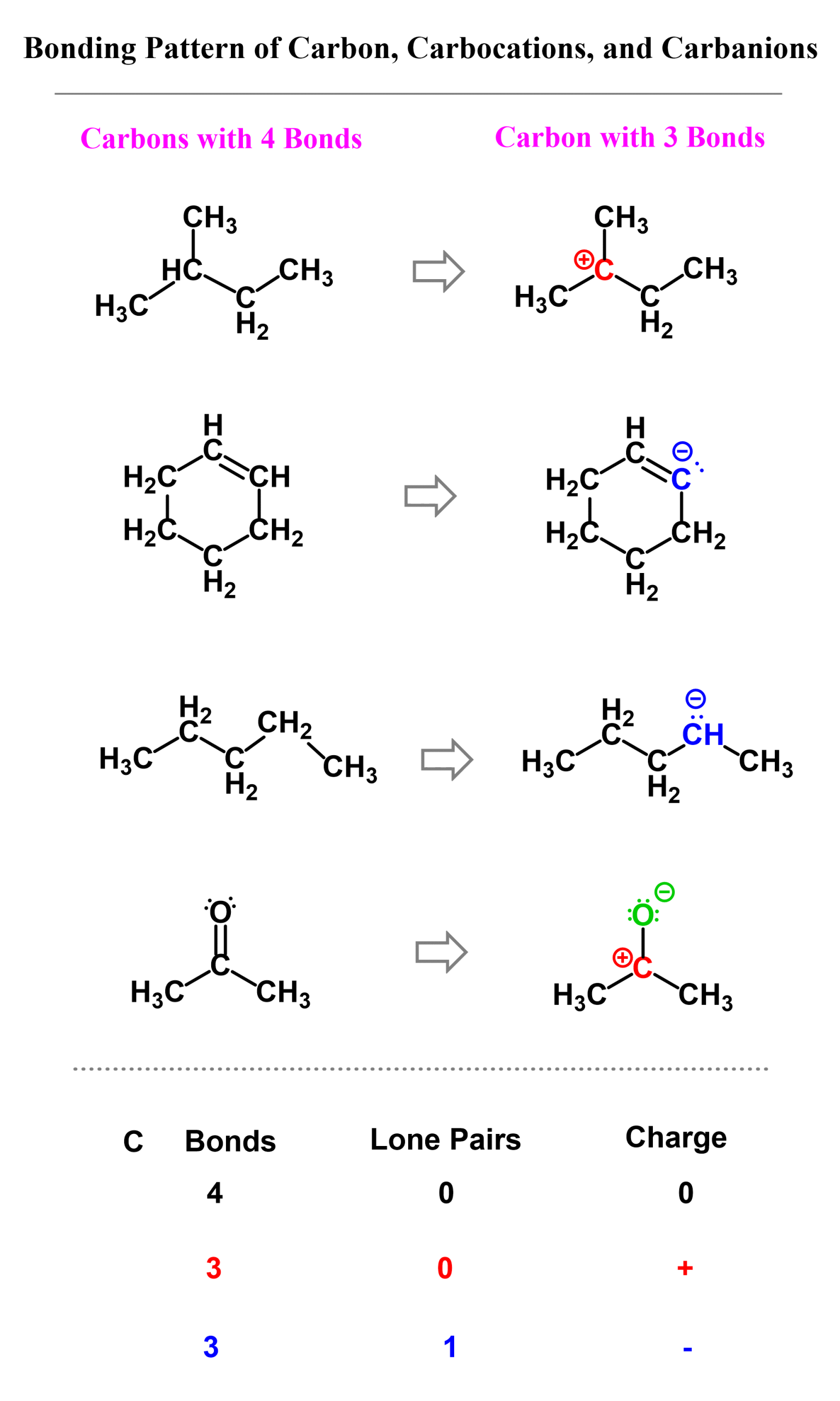

The answer is yes, carbon can have three bonds, but we need to know when and how that happens. In short, this is possible with the right combination of bonds, lone pair, and a formal charge. There are two possibilities for carbon having three bonds, and that is either in carbocations or carbanions.

Both of these follow the octet in that they cannot exceed it! There can be fewer than 8 electrons around the carbon, but never more than that.

In carbocations, there is a carbon that is positively charged because it only has three bonds and no lone pair. Carbocations do not satisfy the octet rule, making them very unstable and reactive. They’ll quickly seek electrons from nearby atoms or molecules and react with them to form new molecules.

Carbanions contain a carbon with three bonds and a lone pair, which makes them negatively charged. Unlike carbocations, carbanions do satisfy the octet rule, but they are still unstable because they carry excess electron density. They’ll look to react with electron-poor species (electrophiles).

Here are some examples of molecules containing carbon atoms with three bonds. Pay attention to the number of lone pairs and formal charges:

Here is also a table that includes the bonding patterns of nitrogen, oxygen, and halogens in organic chemistry. As a side note, remember that hydrogen can only have one bond.

Check the article “Bonding Patterns in Organic Chemistry” for more details and how lone pairs and formal charges come to the rescue when these atoms do not follow their standard bonding patterns.

Check Also

- Lewis Structures in Organic Chemistry

- Bonding Patterns in Organic Chemistry

- How to Determine the Number of Lone Pairs

- sp3, sp2, and sp Hybridization in Organic Chemistry with Practice Problems

- How to Quickly Determine The sp3, sp2, and sp Hybridization

- Bond Lengths and Bond Strengths

- VSEPR Theory – Molecular and Electron Geometry of Organic Molecules

- Dipole-dipole, London Dispersion, and Hydrogen Bonding Interactions

- Dipole Moment and Molecular Polarity

- Boiling Point and Melting Point in Organic Chemistry

- Boiling Point and Melting Point Practice Problems

- Solubility of Organic Compounds

- General Chemistry Overview Quiz

- Bond-Line or Skeletal Structures

- Functional Groups in Organic Chemistry with Practice Problems

- Bond-line, Lewis and Condensed Structures with Practice Problems

- Curved Arrows with Practice Problems

- Resonance Structures in Organic Chemistry with Practice Problems

- Rules for Drawing Resonance Structures

- Bonding Patterns in Organic Chemistry

- Major and Minor Resonance Contributor

- Significant Resonance Structures

- How to Choose the More Stable Resonance Structure

- Drawing Complex Patterns in Resonance Structures

- Localized and Delocalized Lone Pairs with Practice Problems

- Molecular Representations Quiz