The presence of a lone pair on an atom sometimes brings an exception to the shortcut for determining its hybridization.

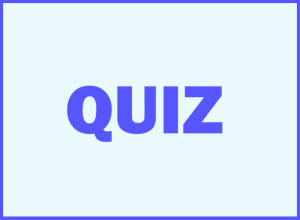

Recall that for a quick and accurate way of determining the hybridization, we count the steric number of the atom – that is, the number of atoms and lone pairs it has.

For example, this is how we quickly determine the hybridization of carbon atoms in the following molecule:

Notice that multiple bonds do not matter; it is atoms + lone pairs for any bond type.

Check this detailed article on hybridization if this looks unfamiliar or if you need a refresher before moving on.

Lone Pairs and Hybridization

A common exception to this strategy is when the lone pair on the atom is delocalized. In other words, it is in resonance with an adjacent pi (π) bond.

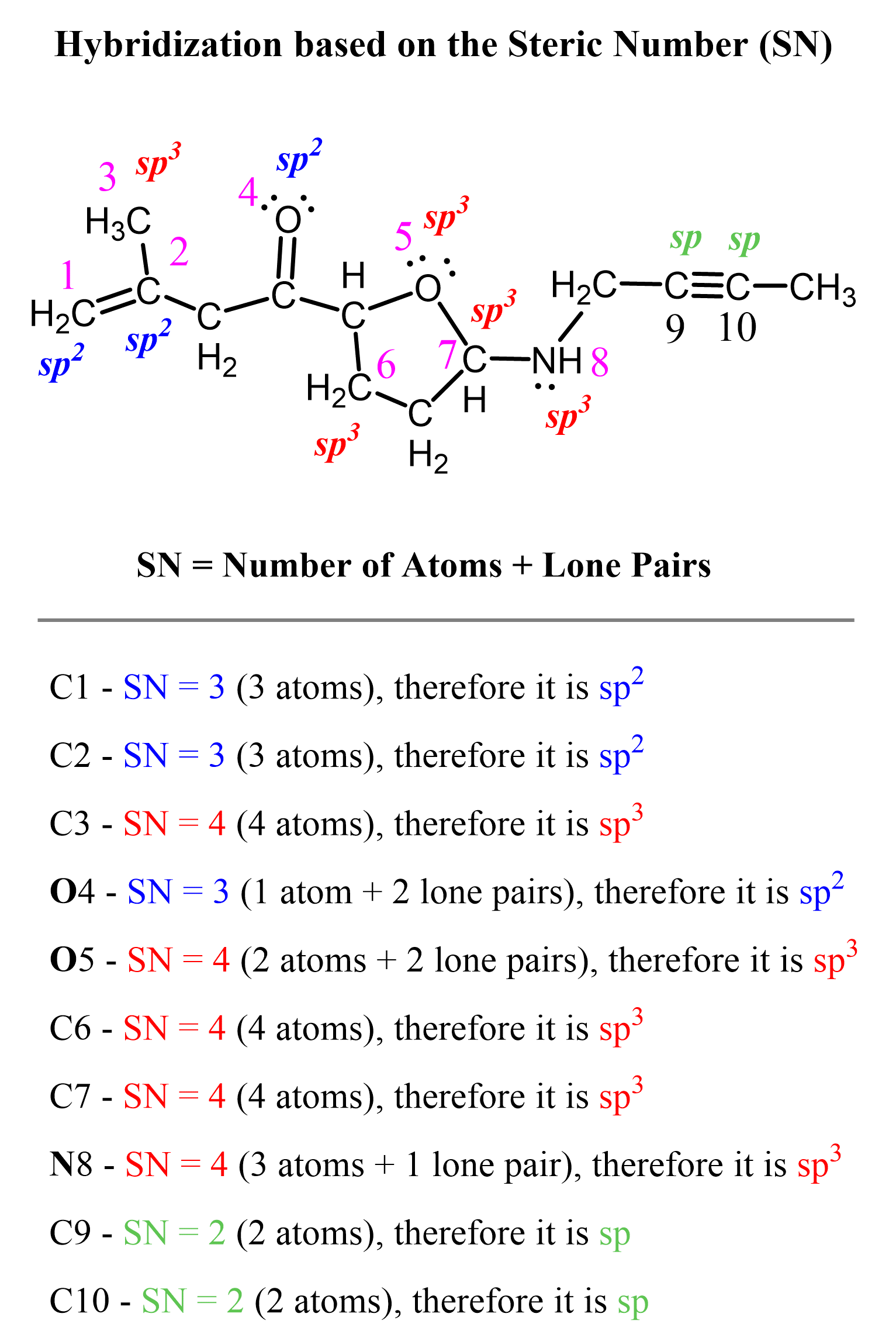

For example, we may expect the hybridization of the nitrogen in amides to be sp3 because its steric number is 4 (3 bonds and a lone pair):

However, the nitrogen in amides is sp2 hybridized because its lone pair is delocalized over the carbonyl oxygen through the C=O pi bond:

Remember, in order to be in resonance, the p orbitals must be aligned parallel, which is only possible if the given atom is sp² hybridized:

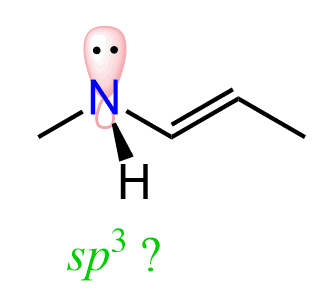

A similar situation occurs in esters and carboxylic acids, where the single-bonded oxygen delocalizes a lone pair toward the carbonyl group:

Remember that resonance structures are not the actual representation of the molecule — they are used to simply show the electron distribution and the reactivity of the molecule.

The most accurate representation is given by the resonance hybrid, while the other forms are the major and minor resonance contributors to it.

Another example of “unexpected sp2 hybridization” is in enamines and vinyl ethers, where the nitrogen and oxygen are connected to a C=C double bond. Just like in esters, the expected hybridization of the oxygen is sp3 because it only has two single bonds and two lone pairs. However, the resonance delocalization of these electrons makes them adopt sp2 hybridization.

Can Atoms connected to π Bonds be sp3 hybridized?

A question you may be wondering at this point is whether it is possible to have a lone pair on an atom directly connected to a π bond, yet still not participate in resonance.

Although this usually won’t be the case, especially in Organic Chemistry 1 classes, nonetheless, there are some exceptions here too. The most notable is perhaps the factor of aromaticity. To keep it short, aromatic compounds have additional stability, and they may include or exclude lone pairs, changing hybridization to become aromatic or avoid being so.

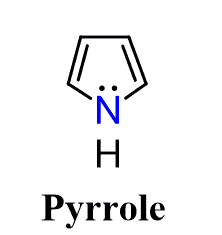

For example, pyrrole is an aromatic compound because of the “unexpected” sp² hybridization of the nitrogen atom:

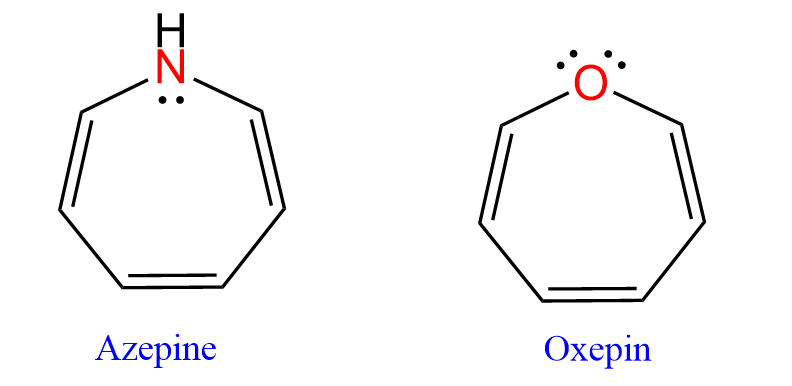

On the other hand, azepine and oxepin are debated to have sp³-hybridized nitrogen and oxygen atoms, which allows them to avoid becoming antiaromatic (very unstable).

We have a separate article on aromatic and antiaromatic compounds, so feel free to read it for a more detailed discussion on this topic. However, don’t worry about it if you are in the first semester of organic chemistry and just starting to cover the hybridization theory of atomic orbitals.

Summary: When Lone Pairs Change Hybridization

In most cases, we can quickly determine the hybridization of an atom by counting its steric number by adding up the number of atoms and lone pairs attached to it. However, this shortcut doesn’t apply when lone pairs are delocalized through resonance.

In such cases, atoms like nitrogen and oxygen may adopt sp² hybridization instead of the expected sp³, to participate in resonance delocalization. This exception explains the observed geometry in functional groups like amides, esters, carboxylic acids, vinyl ethers, and enamines.

So, as a pattern, keep in mind that heteroatoms connected to π bonds, whether it’s a C=C or C=O, are typically sp²-hybridized.

Check this 60-question, Multiple-Choice Quiz with a 2-hour Video Solution covering Lewis Structures, Resonance structures, Localized and Delocalized Lone Pairs, Bond-line structures, Functional Groups, Formal Charges, Curved Arrows, and Constitutional Isomers.